Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is caused by restricted flow through the pulmonary arterial circulation resulting in increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and ultimately in right heart failure. There is a progressive increase in PVR over time as a result of extensive pulmonary vascular remodelling owing to proliferation of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. Excessive matrix deposition, in situ thrombosis and pulmonary vasoconstriction contribute to the disease process.1 According to the guidelines published by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), PAH is defined as an increase in mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAPm) ≥25 mmHg at rest as assessed by right heart (RH) catheterisation.2 Despite therapeutic advances, no currently available drugs are able to cure PAH or modify the disease course. In the majority of patients, the condition gradually deteriorates despite treatment escalation. During the late stage of disease, lung transplantation may be indicated, but only a limited number of patients have access to this intervention because of a lack of donors, the complexity of the procedure and numerous contraindications. In a selected group of patients an atrial septostomy may be employed as a palliative measure.

Although long-term survival has improved in recent years, the prognosis for PAH is poor and mortality remains unacceptably high. A recent comprehensive analysis of survival from time of diagnosis in a large cohort of patients with PAH found one-, three-, five- and seven-year survival rates from time of diagnostic right-sided heart catheterisation were 85, 68, 57 and 49 %, respectively. For patients with idiopathic/familial PAH, survival rates were 91, 74, 65 and 59 %, showing a considerable improvement in survival in the past two decades, probably owing to a combination of changes in treatments and improved patient support strategies.3 Five-year survival in a recent study of almost 500 patients with idiopathic PAH (iPAH) and heritable PAH (HPAH) was approximately 60 %.4 The prognosis is worse in scleroderma-related PAH with a three-year survival rate of 47 % reported in a recent large study.5 However, these figures contrast significantly with more optimistic survival rates reported in the open-label phases of clinical trials and suggest that adequate long-term disease control is not being achieved by current therapeutic approaches.6–8

PAH patients are categorised according to four functional classes (FC I–IV), defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO). These characterise PAH based on severity of symptoms and signs of right heart failure, according to the degree of everyday physical activity that the patient can carry out without impairment. The scale ranges from I (no limitation in physical activity) to IV (inability to carry out physical activity without symptoms, or with symptoms present at rest).2 This simple classification system, despite its subjectivity, is useful and effective in basic risk stratification, and serves as a decision-making tool when initiating treatment.

Therapeutic Options for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Two decades ago, PAH was considered an untreatable disease. Following the introduction of effective therapies, this has changed. Three classes of drugs have been approved for the treatment of PAH: firstly, prostanoids, secondly, endothelin-1 receptor antagonists (ERAs) such as bosentan (Tracleer®), and ambrisentan (Volibris®),9–11 and thirdly, phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors (sildenafil and tadalafil).12,13 All currently available drugs act as pulmonary vasodilators, but they also affect the mechanisms involved in pulmonary vascular remodelling. However, while ERAs and PDE5 inhibitors provide symptomatic relief and improve functional and haemodynamic outcomes, none of these therapies are curative and only prostanoids have a proven effect on mortality.14

Prostanoids exert their therapeutic effect by replacing endogenous prostacyclin, production of which is decreased or absent in the pulmonary vessels of patients with PAH.15 Several prostanoids are approved for PAH: intravenous (IV) epoprostenol (Flolan® and Veletri®),16 IV and subcutaneous (SC) treprostinil (Remodulin®) and inhaled iloprost (Ventavis®), though the latter requires frequent administration and has lower long-tem efficacy.17 The efficacy and safety of prostanoids has been demonstrated in clinical trials and long-term studies.7,8,18,19

Combination therapy is becoming a popular treatment approach in PAH.20 In a meta-analysis of six trials including 858 PAH patients it was concluded that treatment of PAH with combination therapy improves multiple clinical and haemodynamic outcomes, but it has no effect on mortality.21 However, recent data on upfront combination therapy have demonstrated dramatic improvement in many haemodynamic variables, exercise tolerance and functional class (FC).22 In a French study, 10 patients with FC III or IV at baseline PAH were treated with upfront combination epoprostenol, bosentan and sildenafil for a median duration of 18.5 months. Among the seven patients in whom four-month follow-up data were available, all improved to FC I or II and showed a mean fall in PVR of 71 % relative to baseline. In a separate study, epoprostenol and bosentan combination therapy were compared with matched controls treated by epoprostenol monotherapy. The sample cohort comprised 16 FC III patients and 7 FC IV patients. After four months, there were significant improvements in six-minute walking distance (6MWD) and PVR that were maintained long-term (30 ± 19 months). At one, two, three and four years, overall survival was estimated at 100, 94, 94 and 74 %, respectively and transplant-free survival estimates were 96, 85, 77 and 60 %, respectively. Compared with matched controls started on epoprostenol monotherapy, there was an improvement in overall survival in the combined therapy group (p=0.07).23

There is a need to differentiate between currently available therapies and to identify which treatment responses have the most prognostic value. Right ventricular haemodynamic parameters have been used as the endpoint of many clinical studies. However, this is not the sole factor in determining long-term response to therapy – survival estimates based on haemodynamics are often considerably lower than those obtained in open-label and registry studies where one-year survival rates of 88–97 % have been observed.24

The haemodynamic parameters with greatest predictive power of survival are mean right atrial pressure (mRAP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and cardiac index (CI).24

Parenteral prostanoid therapy is currently the most effective treatment available for moderate to severe PAH, and to date, epoprostenol is the only therapy known to have a long-term impact on mortality.25 However, the use of epoprostenol is complicated by its short half-life (3–5 min), necessitating continuous infusion by a pump and a permanently implanted central venous catheter, with the associated risks of infections, thromboembolism and pump malfunctions.26 Treprostinil, a stable prostacyclin analogue, can be administered by IV or SC infusion, avoiding these risks, although SC administration, which involves a microinfusion pump and a small SC catheter, induces local side effects (such as severe infusion site pain).27 Infusion site pain decreases over time particularly when the same site is maintained for more than seven days.28 Topical ointment, cooling or cold, is also helpful.29

A growing body of data supports the long-term use of treprostinil in PAH. In a long-term study of SC treprostinil monotherapy, survival was 87–68 % over 1–4 years and 72–91 % in a subset with HPAH.30 In another observational long-tem study survival was 88.6 and 70.6 % at one-year and three years, respectively.28 A study in the Czech Republic also demonstrated significant improvements in functional capacity after three years of treprostinil therapy.31 In a registry study of FC III/IV PAH patients over 11 years, it was found that first-line treatment with SC treprostinil is safe and efficacious in the long term. If up-titration beyond six months is tolerated, effective doses are reached (stable median doses >37.5 ng/kg/min were achieved in 71.0 % of patients by year three of treatment and in 92.3 % by year five) and outcomes are good.6

Despite impressive clinical trial data, several studies proved that after an initial period of improvement, clinical worsening is commonly observed following treatment with oral drugs, leading to the need for prostanoid as an add-on therapy.10,11,32,33 It is also becoming increasingly apparent that regimes using oral therapies as first-line treatment are inadequate and require the use of prostanoids. A retrospective analysis of 103 consecutive FC III/IV IPAH patients treated with bosentan found that almost half (44 %) of the patients required prostanoid therapy during follow-up.34 A study in Amsterdam found that FC III PAH patients at this centre received first-line oral therapy as a standard treatment followed by addition of prostanoids on clinical worsening. The mean improvement in 6MWD after four months of prostanoids was 86 m (p<0.01) in the bosentan group versus 41 m (p<0.05) in the bosentan–sildenafil group, and these improvements persisted at long-term follow-up.35

Despite the well-documented efficacy of prostanoids, it appears that there is resistance among patients and physicians to undergo therapeutic escalation to prostanoid treatment. Data from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) indicate that 57 % of all patients and 40 % of FC IV patients who died of PAH were not treated with a prostanoid at the time of their death.36 The study concluded that FC III patients with PAH require more frequent monitoring and more aggressive treatment in an attempt to prevent clinical decline. A study of patients (n=821) taking bosentan as first-line therapy found that 90 % of PAH patients who died had not undergone any changes or additions to their therapeutic regime.37 In a retrospective review of all incident cases of PAH between 2001 and 2009 in Glasgow, only 25 % (n=8) of patients who died (n=28) were receiving prostanoids at the time of death.38

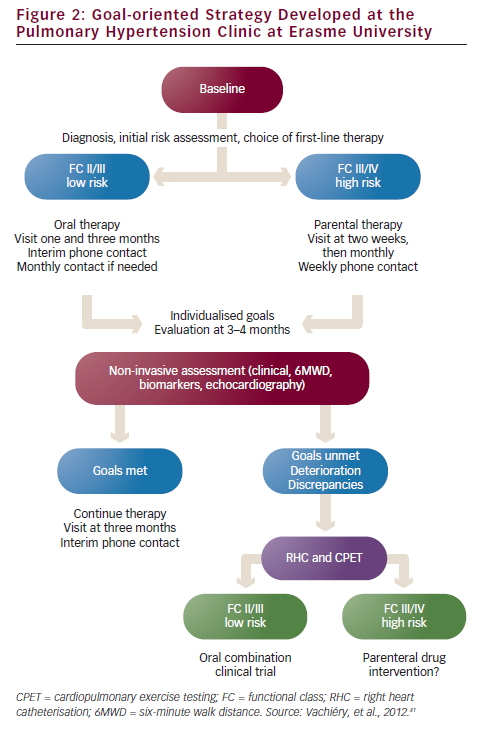

In a recent study conducted in a PAH specialist centre in Rome, it was demonstrated that patients on oral treatment have delayed referrals to expert centres for prostanoid therapy, and that this has a significant impact on prognosis. Most of the patients referred to the centre on oral therapy were in NYHA class IV and needed urgent prostanoid therapy. Of the 57 referred patients, the overall survival at one, two, three and four years was 85, 69, 55 and 43 %, respectively (see Figure 1). The risk of death progressively increased in accordance with modality of access to prostanoid therapy, thereby highlighting the consequences of late referral. Non-survivors had a worse FC III/IV (p<0.01) and exercise capacity on 6MWD (254 versus 354 m; p<0.01) than survivors. Non-survivors were more frequently taking oral therapy (83 versus 36 %; p<0.01) and had a higher rate of urgent prostanoid treatment (69 versus 17 %; p<0.0001).39

There is a need for clearer guidelines on when prostanoids should be first-line therapy. The availability of, and ease of use of, oral therapies may have deterred patients from choosing the optimum therapy or may at least delay initiation of treatment at late stages and thus limit its therapeutic potential. Furthermore, data on oral therapies from short-term clinical trials could be interpreted as indicating greater efficacy in PAH than is the case. Initiating IV or SC prostanoid treatments may consequently be delayed. While treprostinil is approved for treatment of FC III and IV, oral therapies are generally employed in FC II and ‘early’ FC III PAH. Prostanoid treatment has typically been reserved for FC IV patients and FC III patients who are deteriorating or refractory to oral therapies,40 but prostanoid use is often left until too late, by which time poor outcomes are inevitable.39

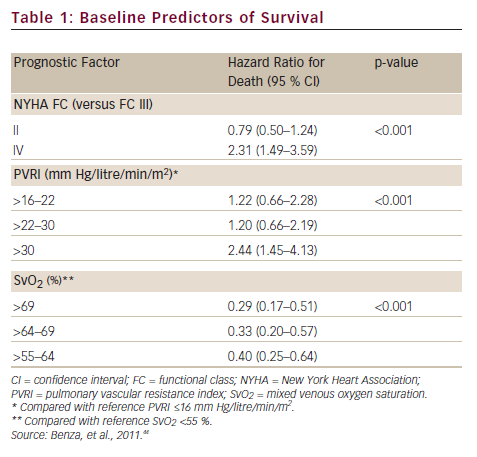

The PAH clinic at Erasme University (Brussels, Belgium) has developed a treatment algorithm for the treatment of the various classes of PAH (see Figure 2).41 However, questions remain regarding the definition of treatment goals and assessing whether patients are achieving these goals. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential to ensure disease management and therapy compliance. Nurses provide a vital link between the patient and physician, educating patients on disease, treatment and impact on daily life, and providing emotional support.

Two treatment strategies have been proposed in PAH:

- the ‘goal-oriented’ approach, which uses known prognostic indicators as treatment targets, allowing early intervention and therapeutic escalation before patients deteriorate. This strategy requires the identification of parameters that correlate with the risk of deterioration and mortality;42,43 and

- the ‘hit hard and early’ approach administers the maximum tolerated therapy as early as possible in the disease process, utilising high doses of SC or IV prostanoids or combination therapy.20 However, the latter approach has been criticised because of cost, side effects and problems associated with parenteral administration.

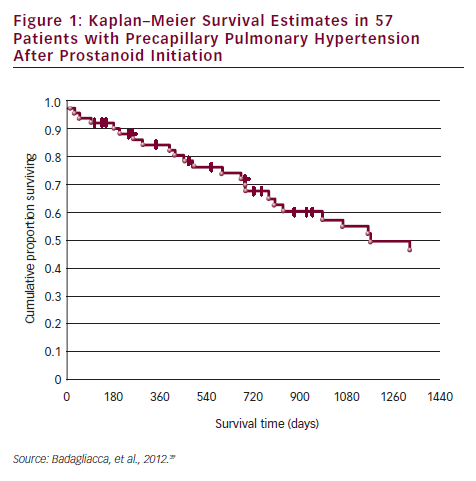

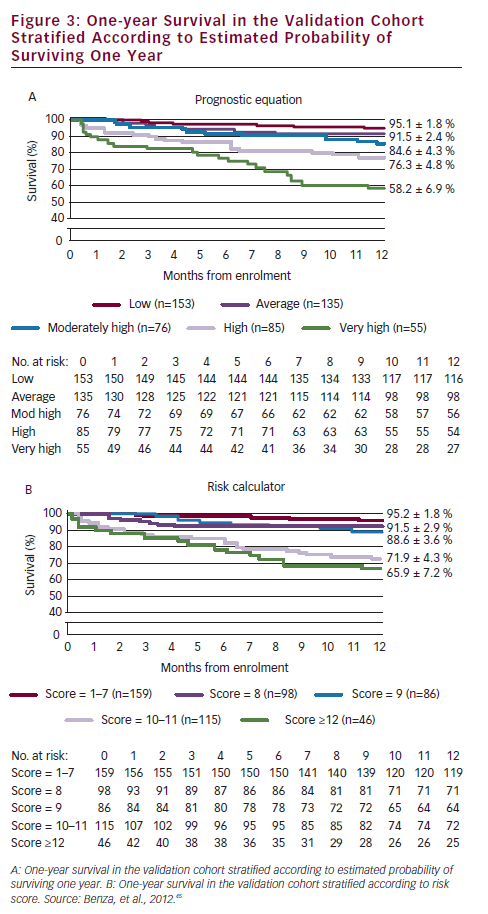

A prerequisite for appropriate use of the hit hard and early strategy is to accurately assess the patient’s risk of a poor short-term prognosis in which the disease will progress rapidly. In a retrospective review of data from 811 patients with PAH, disease aetiology, baseline factors including functional class, pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), on-treatment factors such as 6MWD, SvO2 and treprostinil dose were found to be predictors of long-term survival. Treprostinil dose of ≥40 ng/kg/min (p<0.001) and every 10 ng/kg/min dose increase (p=0.009) resulted in improved long-term survival. In a multivariate analysis, only SvO2, 6MWD and treprostinil dose were significant on-treatment predictors (p<0.02) of survival (see Table 1).44 Based on these data, a predictive algorithm and simplified risk score calculator has been devised, which is useful in rapid identification of individual patients with high-risk of mortality in which aggressive first-line treatment is reasonable (see Figure 3).45

Prostacyclins have become the treatment of choice in patients with severe PAH, but historical data from two expert centres suggest that the use of IV epoprostenol may also benefit patients in less advanced stages of disease.46 Recent data from the REVEAL registry shows that patients who improve from FC III to FC I/II have a better two-year survival compared with patients who remain FC III.47 On the other hand, clinical worsening in the first year post-enrolment results in a significantly worse prognosis.48 FC III PAH patients are a large and heterogeneous group who require more frequent monitoring and more aggressive treatment to prevent clinical decline.

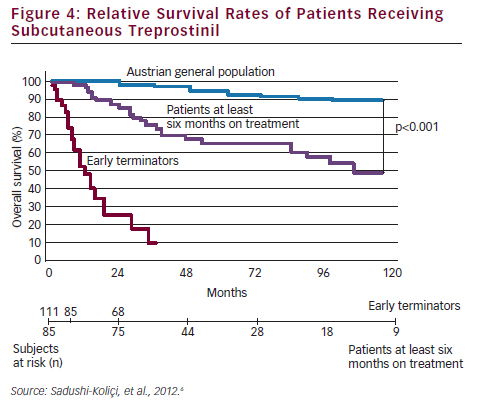

To date, all clinical trials performed on PAH drugs have been designed to demonstrate the short-term clinical efficacy, using haemodynamic parameters or exercise capacity as the primary endpoint. Such studies have failed to demonstrate the efficacy of SC treprostinil with only a modest improvement in exercise capacity shown in the pivotal 12-week study that led to its approval.27 A recent prospective registry study in an expert centre in Vienna analysed data from 111 patients treated using the hit hard and early approach, using first-line SC treprostinil.6 Treprostinil was initiated at a dose of 1.25 ng/kg/min, and the dosage adjusted at weekly intervals for six months, and then at a mean of every 4.5 months (range, 3–6 months), with a goal of achieving 30 ng/kg/min after one year.

Overall survival rates, including all patients ever started on SC treprostinil, were 84, 53 and 33 % at one, five, and nine years, respectively. The survival rates of patients treated at least six months were even more impressive: rates of 96, 78 and 57 % at one, five and nine years, respectively, were reported (see Figure 4). The Vienna study concluded up-titration was essential in the first six months; that patients who remain on treatment beyond the third year have an excellent prognosis and that although 40 ng/kg/min appears to be an effective dose of SC treprostinil, the higher the dose necessary to maintain a stable condition, the worse the prognosis.6 On the basis of these data, it seams reasonable to apply the hit hard and early approach at the beginning of the treatment in patients with high probability of fast disease progression.

Conclusions

PAH is often diagnosed late, resulting in progressive deterioration and premature death. However, despite advances in treatment and management, the disease remains incurable. More than 20 years ago, prostacyclin and its analogues provided a critical breakthrough in the treatment of PAH, but the emergence of oral therapies has resulted in their employment at too late a stage in the disease process. It remains questionable whether oral therapy actually improves a patient’s condition by any objective criteria or merely delays advanced treatment. Recent evidence has demonstrated that prostanoids remain the most effective treatment strategies for PAH, with sustained improvements in the functional capacity and haemodynamic profile, and should be used at an early stage of disease management, either as monotherapy or in combined therapy with oral agents. Future directions in PAH research should include an improvement in the mode of delivery of prostanoids and the development of new drugs acting on different targets.