Women are under-represented in cardiology workforces.1–4 This under-representation has an impact at the physician and patient level and has been linked to poor outcomes for women with cardiovascular diseases.1,5 Available data on transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and other structural interventional operators suggest that women account for a very small proportion of proceduralists.1–4,6 This under-representation persists despite the Ottawa 2010 consensus recommendations that specialist training should aim to produce a workforce that is broadly representative of the population that it serves.7 There is a paucity of data globally addressing the representation of women among structural interventional cardiologists, and a lack of clarity as to whether this hypothesised under-representation affects recruitment to landmark trials, subsequent guideline recommendations, patient selection for treatment, or outcomes. This review evaluates the representation of women in structural cardiology at both the patient and physician levels, sex differences in the workforce, trial recruitment, referral for invasive procedures, and outcomes.

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

TAVR was first performed 20 years ago. TAVR has been a transformative innovation that has changed the lives of patients previously considered inoperable. As TAVR case numbers began to increase, patient and operator selection were both hot topics and in many cases politically loaded topics. Patient selection, procedural performance and postprocedural care were all carefully vetted and so too were clinical site and operator selection.8

TAVR Operators

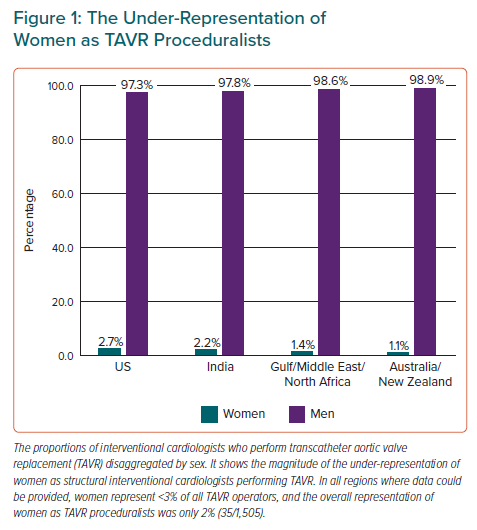

Women are under-represented among TAVR operators. Little published data on operator numbers and percentages are available. According to pooled data from the US, Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand, internationally, women make up only 7% of all interventional cardiologists, and the inclusion of women as structural proceduralists is substantially lower. What we do know suggests that we are not only failing to meet expectations recommended by the Ottawa consensus, but we are also failing to appropriately include women as TAVR operators in most centres.7 Based on current data described in detail below, in the US, India, Australia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Egypt, Tunis, Algeria, Morocco, Jordan and Lebanon only 2% (35/1,505) of all interventional cardiologists performing TAVR are women (Figure 1).1,6

The US, Australia and New Zealand have published TAVR operator numbers, but data are not available in most countries, including Canada, the UK and Europe.1,6 Globally, where professional interventional societies do not collect these data, numbers can often only be sourced through device companies. In the US, Simpson et al. in 2021 studied interventional cardiologists who were TAVR operators and found that only 2.7% (26/947) were women.6 National Interventional Council (NIC) data from the Cardiological Society of India cross-checked with Medtronic data found that of the 184 interventional cardiologists in India who have performed TAVR, only 2.2% (4/184) are women. In Australia and New Zealand Burgess et al. in 2018 found that of interventional cardiologists who were TAVR operators, only 2% were women (1/50).1 Updated data (provided by the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand) from 2022 found no improvement: of the interventional cardiologists registered as TAVR operators in Australia and New Zealand in 2022, only 1% were women (1/90). Further data from the Gulf, Middle East and North Africa (provided by coauthors and cross-checked with industry data) assessing interventionalists from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, Egypt, Tunis, Algeria, Morocco, Jordan and Lebanon showed that 1.4% (4/284) of the interventionalists who perform TAVR were women, (three women in Saudi Arabia and one woman in Morocco).

Sex Distribution of Severe Aortic Stenosis

Aortic stenosis (AS) has been reported to be the most common type of valvular heart disease in developed countries.9 The sex distribution of severe AS varies significantly by data source and by patient age: according to current data, 48–68% of patients with severe AS are women. Pooled data suggest that the sex distribution of severe AS is relatively equal, given that in the overall population 49% of severe AS patients are women, but in the elderly population 55% of patients with severe AS are women.9–11

These percentages are sourced from several large studies as follows. Data from an evaluation of a large US-based electronic health registry of patients with severe AS reported that when all ages were assessed, women represented 48% (20,986/43,822) of all patients, but in patients aged over 80 years, women represented 53% (11,798/22,108) of patients.10 The CURRENT AS (Contemporary outcomes after sURgery and medical tREatmeNT in patients with severe aortic stenosis) registry, a Japanese registry of consecutive patients with severe AS, found that women represented 62% (2,372/3,815) of all patients with severe AS, but for patients 75 years or older, 68% (1,731/2,558) of patients were women.9 The prospective European IMPULSE registry, studying patients newly diagnosed with severe AS from Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and the UK, reported that 48% of all patients were women (1,041/2,171), and of those over 80 years of age, 57% (571/1,006) were women. Taken together these data suggest that 49% (24,399/49,808) of the severe AS patient population are women, but in the elderly population more likely to be suitable for TAVR (i.e. those older than 75 or 80 years of age), 55% (14,100/25,672) of the patient population are women.9–11

Representation and Inclusion of Women as Patients in Landmark TAVR Trials

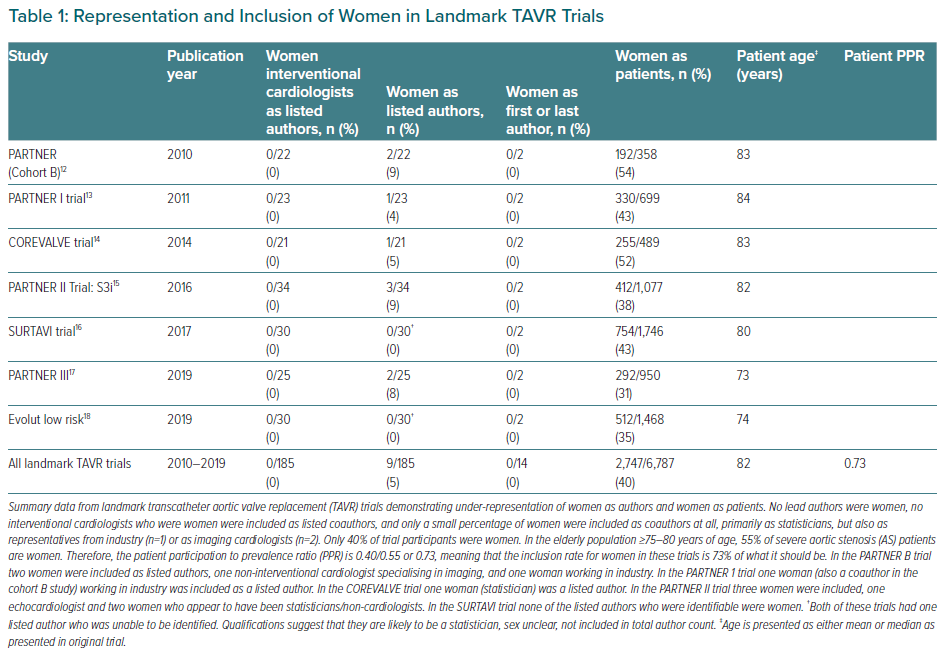

The enrolment of women into major landmark clinical TAVR trials has been variable.12–18 The highest representation in landmark TAVR publications was in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) cohort B study, an early non-randomised study published in 2010 in which 54% (192/358) of all patients were women.12 However, the numbers of women have been lower in randomised TAVR trials since then and are as low as 31% in low-risk TAVR patient randomised controlled trials.17

In landmark studies evaluating TAVR including PARTNER cohort B, the PARTNER I trial, the COREVALVE trial, the PARTNER II S3i trial (intermediate risk), the SURTAVI trial, the Partner III (low-risk patients) trial, and the Evolut Low Risk (Evolut Surgical Replacement and transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Low-Risk Patients) trial, only 40% (2,747/6,787) of participants were women (Table 1).12–18 This is significantly lower than the overall proportion of women with severe AS, described above, of 49%, but inclusion rates are more concerning if population age is considered. The median patient age in these seven landmark trials was 82 years; available data report that 55% of the severe AS population in this age group are women.9–11 Therefore, the true calculated PPR for these TAVR trials becomes 0.73, meaning that the inclusion rate for women in these trials is 73% of what it should be.

This under-representation limits our potential to develop sex-specific strategies or recommendations for our patients with severe AS, or to be certain that current guidelines are appropriate or generalisable for all populations with severe AS.

Representation and Inclusion of Women as Authors in Landmark TAVR Trials

Under-representation of women as trial authors and clinical trial leaders has been shown in cardiovascular research to be independently associated with the under-enrolment of women in randomised controlled trials.19,20 Table 1 summarises the representation and inclusion of women as authors in landmark TAVR trials, and profound under-representation is evident. None of the landmark TAVR trials listed above had first or senior authors who were women, none of the authors were interventional cardiologists who were women, and only 5% of all listed authors in these trials were women (Table 1).

TAVR Registry Data

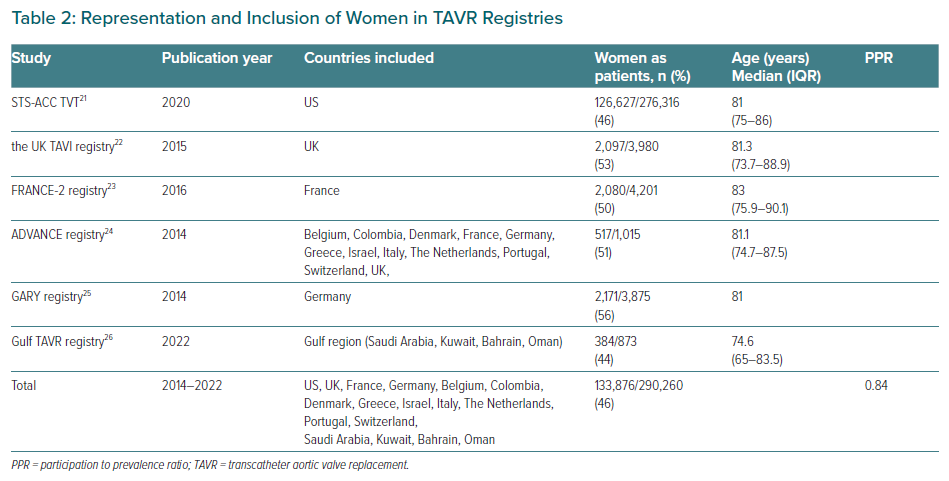

Real-world registry data (Table 2) show that women are also under-represented in TAVR registries, suggesting they may be less likely to receive TAVR treatment even in a non-trial setting. In the major registries, women represent 44–56% of treated patients.21–26 When all patients from these large registries were combined only 46% (133,876/290,260) of patients treated with TAVR were women, meanwhile, as per the data described above, 55% of the severe AS population in this age group are women.9–11 Therefore, the calculated PPR for real-world registry TAVR data is 0.84, meaning that the inclusion rate for women in these registries is 84% of what it should be if treatment with TAVR were distributed equally between women and men with severe AS.

The WIN-TAVI (Women’s INternational Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) registry has been established to address the sex-specific data gap for women treated with TAVR.27 It examines the safety and performance of TAVR using an all-female registry, examines the potential impact of female sex-specific characteristics on clinical outcomes and is the first multinational, prospective, observational registry of women undergoing TAVR for AS. Further sex-specific insights will be also provided by the currently enrolling RHEIA (Randomized researcH in womEn All Comers With aortic stenosis) trial NCT04160130, comparing TAVR with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in women with severe symptomatic AS.28

TAVR Patients and Outcomes

Women with severe AS have different baseline characteristics to men with severe AS. Women are older at diagnosis, have less frequent concurrent ischaemic heart disease or cardiac surgery and higher ejection fractions, but have higher rates of renal impairment, multivalve valve disease, porcelain aorta, surgical risk scores, and more often present in a critical perioperative state.11,29 Frailty assessment is variable, with higher subjective reports of frailty in women in the heart team setting, but non-significant differences when age is also taken into account.11,29 Women also have smaller hearts, smaller more calcified aortic annuli and shorter coronary ostia to annulus heights.11

Sex-based outcome differences in invasively managed severe AS are evident. Large studies and meta-analyses report lower mortality for women with severe AS undergoing TAVR compared with men, despite higher rates of periprocedural complications and older age.11,29–32 The STS-ACC TVT Registry (n=11,808) found that 1-year mortality was lower in women than in men (21.3% versus 24.5%; adjusted HR 0.73; 95%CI [0.63–0.85]; p<0.001), despite poorer in-hospital outcomes and no significant differences in composite adverse clinical endpoints.29

Meta-analyses of randomised trials comparing outcomes in TAVR with SAVR have also found a survival benefit with TAVR in women but not men.33,34 A meta-analysis by Siontis et al. reported a robust survival benefit for patients treated with TAVR over SAVR for women (HR 0.68; 95% CI [0.50–0.91]), but not men (HR 0.99; 95% CI [0.77–1.28]; pint=0.050), with very similar results found in a meta-analysis by Panoulas et al.33,34

The WIN-TAVI registry (n=1,019), described above, enrolled women from 19 European and North American centres (mean age 82.5 ± 6.3 years, mean EuroSCORE I of 17.8 ± 11.7%).27 Transfemoral access rates were 90.6% and new-generation devices were used in 42.1%. In these registry patients the 30-day Valve Academy Research Consortium (VARC)-2 composite endpoint occurred in 14.0% of patients, with rates of all-cause mortality of 3.4%, stroke, 1.3%, major vascular complications, 7.7%, and VARC life-threatening bleeding, 4.4%. Independent predictors of the primary endpoint were age (OR 1.04; 95% CI [1.00–1.08]), prior stroke (OR 2.02; 95% CI [1.07–3.80]), left ventricular ejection fraction <30% (OR 2.62; 95% CI [1.07–6.40]), new generation device (OR 0.59; 95% CI [0.38–0.91]) and history of pregnancy (OR 0.57; 95% CI [0.37–0.85]).27 At 1 year the VARC-2 composite efficacy endpoint rate was 16.5%, with a low incidence of 1-year mortality and stroke.

Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair

Transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVr) was first performed in 2009. Progress in the field of TMVr was not as rapid as that for TAVR, in part due to the anatomically more complex saddle-shaped annulus of the mitral valve. The gold standard treatment for severe mitral regurgitation (MR) is repair or replacement, but up to 50% of patients with severe symptomatic MR are not referred for surgery.35 TMVr is rapidly evolving currently and is considered an appropriate alternative to surgical mitral valve repair for patients with too high a risk for surgery. It is usually performed as an edge-to-edge leaflet repair, although transcatheter mitral valve replacement is also an emerging technology for the treatment of severe MR, with a large number of potential devices currently in development.35

TMVr Operators

Very little available data can be found on the representation of women as TMVr proceduralists, with available data (from Japan, Australia and New Zealand only) suggesting overall rates of 1% (1/86). Rates of representation in hospitals in Japan have been published by Kataoka, who found that only 1.7% (1/58) of the first operators in TMVr procedures were women.36 And according to the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand data, 0% (0/28) of registered TMVr operators in Australia and New Zealand are women.

Sex Distribution of Mitral Valve Disease

Mitral valve disease and specifically MR affect approximately 10% of people older than 75 years of age in higher-income countries. With regard to the sex distribution of severe MR, 50–53% of severe MR occurs in women, with pooled data suggesting that 52% of severe MR occurs in women.37–39 In more detail, Mayo clinic data found that more women (53%, 682/1,294) than men (47%, 612/1,294) have moderate or severe MR.37 Similar findings were reported in a study of community prevalence of MR from the UK, which studied 9,504 patients and reported moderate to severe MR in 203 patients, 55% (111/203) of whom were women.38 The Euro heart survey found an equal frequency of severe MR in women (50%, 198/396) and men (50%, 198/396), and a non-significant trend toward medical management in women (52%, 103/198) compared with men (45%, 90/198; p=0.22).39

Representation and Inclusion of Women as Patients in Landmark TMVr Research

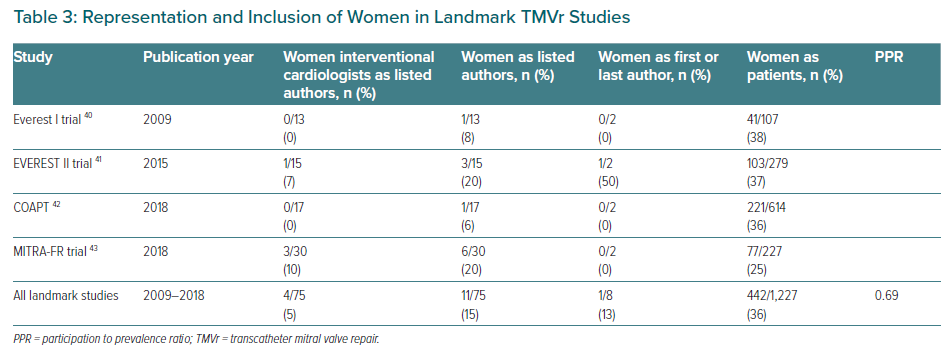

Despite ongoing efforts to increase female enrolment in clinical trials, women have been consistently under-recruited in TMVr trials.40–43 Landmark studies evaluating TMVr (Table 3) include the Everest trials (I and II), COAPT and MITRA-FR. The overall inclusion of women in these landmark TMVr trials is 36% (442/1,227), although population data show that 52% of the severe MR population are women.37–39 Therefore the calculated PPR for representation of women in these landmark trials of TMVr is 0.69, meaning that inclusion rates for women are only 69% of what they should be based on the sex distribution of severe MR in the population.37–39 This significant under-representation of women in TMVr trials will limit our potential to develop sex-specific strategies or recommendations for women with severe MR.

Representation and Inclusion of Women as Authors in Landmark TMVr Trials

Table 3 summarises the representation of women as authors in landmark TMVr trials. Of the landmark TMVr trials listed above only one study had a first or senior author who was a woman. A total of four interventional cardiologists who were women were included as coauthors in these four landmark studies, comprising 5% (4/75) of all author roles. Overall, 15% (11/75) of all listed authors in these trials were women; and the women who were included were more likely to be non-interventionalists (7/11), statisticians, study coordinators or cardiologists specializing in imaging or heart failure rather than interventional cardiologists (4/11).

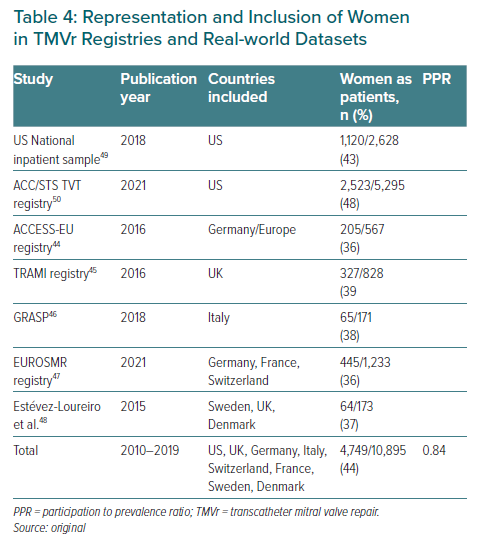

TMVr Registry Data

Registry data show that women are less likely to be treated with TMVr than men.44–50 In the major registries women represent between 36% and 48% of treated patients, with an overall rate of 44% (4,749/10,895).44–50 Table 4 summarises the rates of representation from major TMVr registries: the US National Inpatient Sample (NIS), the American College of Cardiology/Society of Thoracic Surgeons Transcatheter Valve Therapy (ACC/STS TVT) registry, the ACCESS-EU registry, the Transcatheter Mitral Valve Interventions (TRAMI) registry, the GRASP (Getting Reduction of mitral insufficiency by Percutaneous Clip Implantation) registry, the European Registry of Transcatheter Repair for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation (EuroSMR registry) and a multicentre registry from Europe.44-50 Data from these registries show that women are also under-represented in these TMVr registries and comprise only 44% of registry patients rather than the expected 52% based on population data.37–39 Therefore, the calculated PPR for registry patients receiving TMVr is 0.84, meaning that the inclusion rate for women is 84% of what it should be if treatment with TMVr was equally distributed in the eligible population with severe MR.

TMVr Patients and Outcomes

None of the landmark studies of TMVr found sex-based differences in outcomes but all were underpowered to do so, and between them, they included only 442/1,227 patients who were women.41,43 Registry data have shown that women have equal or superior outcomes with TMVr compared with men, but women have poorer surgical outcomes for mitral valve replacement compared with men.51 Several TMVr large studies report that rates of death, postoperative MI and stroke do not differ significantly between women and men, while others report higher death rates among male patients.44,47,50,52–54 Kanitsoraphan et al. reported both higher in-hospital mortality for men (pooled OR 1.81; 95% CI [1.01–3.22]) and overall mortality for men (pooled OR 1.19; 95% CI [1.06–1.33]).54 Villablanca et al. reported a lower adjusted 1-year risk of all-cause mortality (OR 0.80; 95% CI [0.68–0.94]) for women compared with men.50

This is despite significant differences in baseline characteristics, comorbidities and mitral valve morphologies.44–50,53,55 Women referred for mitral intervention are older with fewer comorbidities, higher reported rates of frailty and poorer baseline New York Heart Association (NYHA) class compared with men.44–48,50 They have more complex degenerative disease, more annular calcification and more mitral stenosis compared with men.44,47,55 The ACCESS-EU registry found that women were more likely to have a single clip implanted than men (72% versus 54%) and safety endpoints (including bleeding), 1-year echocardiographic and clinical efficacy results were all similar between the sexes, with no interactions of 12-month survival on multivariate analysis.44 In the TRAMI registry, no differences in mortality were seen but severe bleeding complications were higher in women than in men and re-intervention rates were lower. Women also showed less improvement in functional NYHA class at 1-year follow-up.45 The ACC/STS TVT Registry of commercial TMVr procedures using MitraClip found that women were older, with fewer comorbidities, but had lower long-term adjusted all-cause mortality at 1 year, and there was no difference in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events between women and men.50

Participation of Women as Proceduralists in Other Structural Cardiac Procedures

This review focuses on TAVR and TMVr as examples of frequently performed procedures in structural interventional cardiology. Other structural interventional cardiology procedures such as left atrial appendage closure, closure of atrial and septal defects, and percutaneous procedures to treat tricuspid and left ventricle dysfunction are also performed. The under-representation of women among left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) implanters has been documented by Coylewright et al. and is discussed briefly below. No other data documenting the participation of women as proceduralists in the remaining structural cardiac procedures were found.4

LAAC Implanters

In the US, Coylewright et al. analysed the initial 2 years of LAAC approval to assess the sex distribution in LAAC implanters.4 They found that 2.9% (26/886) of watchman implanters were women (data documenting LAAC implanters in other countries are not published). The Coylewright et al. study also provided insights into the impact of women as leaders and the importance of visible female leaders, allies and mentors.

The Under-Representation of Women in Leadership

Coylewright et al., when evaluating the representation of women as LAAC implanters, also found that hospitals with women in leadership positions were fourfold more likely to also have a woman implanter (OR 4.24; 95% CI [1.17–15.4]).4 Fewer than 4.8% of hospitals had a woman in a leadership role, 0.7% (3/414) of hospitals had a woman in the position of cardiac catheterisation lab director, 2.6% (11/414) of hospitals had a woman as director of electrophysiology and 2.6% (11/414) had a chief of cardiology who was a woman.4

Discussion, Solutions and Conclusions

Data from this review show that women are profoundly under-represented in structural interventional cardiology: only 2% of all TAVR and 1% of TMVr proceduralists are women. Although the training programmes and selection processes vary internationally, these numbers vary little between countries, suggesting that the challenges are universal and problematic in both high-income and lower-income countries.

Women also remain under-represented as participants in structural clinical trials. Using PPR, the inclusion rate for women in TAVR trials is 72% of the expected rate based on disease prevalence data, and for TMVr trials, the PPR is 69% of the expected rate. Registry data also suggest that women may receive less treatment of severe AS and severe MR with TAVR or TMVr in real-world settings, with a PPR of 84% of the expected rates for both TAVR and TMVr. These disparities in access for women to structural interventions are not due to poorer outcomes driving treatment selection. Contemporary data report equal or superior risk-adjusted survival rates for women treated with TAVR or TMVr when compared with men, despite the differing patient baseline characteristics and in-hospital adverse events.11,29–32,44,47,50–54

The representation of women in structural cardiology at both a patient and physician level is an important equity issue. Randomised trials in cardiovascular medicine with women in leadership roles, or as trial authors, are associated with higher recruitment of women as participants, and hospitals with women in cardiology leadership positions are more likely to employ women as structural interventional cardiologists.4,19,20 Physician–patient sex concordance is also associated with increased patient survival for women with cardiovascular disease and for women undergoing surgery.5,56,57 Greenwood et al. found that the outcome gap for women admitted with MI was not evident when women were treated by women, and similar data have been reported by Tsugawa et al.5,56 Both sets of authors report a survival benefit for women treated by women physicians.5,56

Proposed Solutions

Role Models, Mentors and Workplace Diversity

The research by Coylewright et al. demonstrates clearly that under-representation begets under-representation.4 The under-representation of women in the structural workforce is likely to have a negative impact on medical students, trainees, physicians, cardiologists and patients.1,4–6,58,59 Optimal patient care is provided by a diverse and gender-balanced physician workforce.5,57,60–67 Patients are more likely to trust physicians who appear similar to themselves and are more likely to have better outcomes.5,56,68 Douglas et al. have previously demonstrated that after the subject matter itself, the two most commonly identified factors guiding trainees’ specialty selection are a supportive role model and positive encouragement.58 If our trainees do not see women in these roles or have the support of women in leadership roles, they are less likely to choose procedural subspecialties or be able to navigate the career barriers they face, therefore access to visible mentors and sponsors is recommended.4,58 Mentors and peer networks are critical to advise and support trainees through the challenges of training. Mentorship is key for career development and can improve diversity, inclusion and retention in the workplace.69 Workforce diversity is important, given that sex and ethnic concordance are associated with mentoring success. Policies are needed to ensure equity, inclusion, diversity and a sense of belonging in our workplaces as well as to ensure freedom from bias, discrimination and harassment, as is an audit of these policies to confirm that they are successful.3,70–72

Active Recruitment of Diverse Leaders

The low representation of women as patients in cardiovascular clinical trials and the undertreatment of women with contemporary structural heart therapies occurs in the context of marked exclusion of women as clinical trial investigators, study leaders and authors.19,20 Data show that when women serve as clinical trial leaders the trials are more likely to include a broader demographic of recruited patients, and are more likely to include ethnicity data and information about diverse patient populations, which improves study validity, generalisability and subgroup analysis.20,73 Well-powered sex-specific data are essential to inform guidelines and real-world practice, and stalled recruitment and retainment of women in interventional cardiology will limit our ability to reap the proven benefits associated with diverse workforces and workplaces.5,56,60,67 Policies addressing known barriers to the advancement and visibility of women in this field need to be enacted by individuals, by structural heart industry partners and by national professional societies.72

Existing leaders in clinical trials should have succession plans that correct under-representation with the goal of increasing sponsorship of women, and specific public actions of support are needed to intervene on exclusionary behaviour.74

Industry partners investing in large structural heart clinical trials should also be a focus because they play a disproportionately large role in shaping structural heart leaders via investigator and leader selection. There is limited transparency in this process currently. Leadership selection processes in the current system affect the selection of study site and site primary investigator, which leads to sex and racial disparities in cardiovascular clinical trial participation and the under-representation of women, non-white groups, non-affluent patients, populations and hospitals.19,20,64,65,73 Overt policy within industry and review of leadership and primary investigator selection is recommended to ensure diversity. Diversity and inclusion sub-committees specifically focused on representative inclusion at all levels are needed.

National professional societies can also provide solutions given that they play a critical role in connecting physicians with industry leaders, through national meetings. Professional societies and other non-profit organisations such as Women as One have a unique opportunity to promote diversity when choosing leaders to serve as meeting faculty or clinical trial leaders, investigators and authors. Active recruitment processes, transparent metrics and open calls for positions are recommended, as are formal codes of conduct, guidelines and policies that outline priorities for diversity and inclusion efforts and protect individuals from gender and sexual harassment to ensure that change is effective.70

Conclusion

Women with valvular and structural heart disease are under-represented in registries and clinical trials. These are the trials upon which guideline recommendations are based.51 Women are disproportionately under-represented in leadership and authorship of clinical trials, they are also under-represented in the medical workforces that treat these conditions, cardiology, interventional cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery. Women are profoundly under-represented in structural interventional cardiology, and the magnitude of this under-representation and its impact should not be underestimated.1

Our data show that cardiology, interventional cardiology, structural cardiology and their associated clinical trial committees remain exclusive fraternities. Each step into these specialties, subspecialties and committees is more likely to be successful with strong allies, role models, mentorship and sponsors. In procedural subspecialties these local allies, role models, sponsors and mentors are critical to recruit and retain structural interventional cardiologists and achieve a more diverse workforce. Diversity-focused policies are also needed in industry and clinical trial leadership selection.

The under-representation of women in interventional cardiology, including the structural subspecialties, continues to negatively impact our patients, contributing to the lack of women participants in cardiovascular trials and hindering our ability to generate meaningful, sex-specific data. We must ensure that our training programs seek to include more women in structural fellowships, our hospitals employ more women in structural roles, our colleagues in industry include more women as investigators and on steering committees, and that our national societies lead by actively facilitating positive change.