Intracoronary administration of acetylcholine (ACH) was found to induce paradoxical coronary vasoconstriction due to coronary endothelial dysfunction, according to Ludmer et al. in 1986.1 They carried out incremental dose-up injection of ACH (0.03 μg, 0.3 μg, 3 μg and 30 μg) for 2 minutes with an infusion pump into the left coronary artery (LCA). In 2003, the ENCORE study used intracoronary ACH (2.16 μg, 21.6 μg and 108 μg) with an infusion pump via microcatheter for 3 minutes into the LCA to verify the presence or absence of coronary endothelial dysfunction.2 In contrast, in 1986 Yasue et al. reported the usefulness of intracoronary ACH testing in patients with variant angina.3 They used incremental dose-up of ACH (20 μg, 50 μg and 100 μg into the LCA and 20 μg and 50 μg into the right coronary artery [RCA]) for 20–30 seconds with manual injection. The sensitivity and specificity of ACH testing for patients with variant angina were found to be acceptable.3 Intracoronary ACH testing is clinically used for the investigation of coronary endothelial dysfunction and coronary spasm; however, the procedures and doses involved vary worldwide. In this article, we summarise the information on intracoronary ACH testing with the aim of determining the optimal ACH procedure for verifying the presence or absence of coronary endothelial dysfunction and coronary spasm.

Vasoreactivity Testing for Coronary Endothelial Dysfunction

Furchgott and Zawadzki reported on the essential role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by ACH in vitro.4 If coronary arteries have normal endothelial function without any atherosclerotic lesions, intracoronary injection of ACH dilates the coronary artery. However, if coronary arteries have abnormal endothelial function due to coronary atherosclerosis, intracoronary injection of ACH constricts the coronary artery. As shown in Table 1, the majority of researchers have used relatively low doses of ACH (0.36 μg, 3.6 μg and 36 μg) for 2–3 minutes.5–10 Intracoronary ACH is injected at a constant flow rate using pump infusion without a pacemaker, and the target coronary artery is usually the left anterior descending artery.11–13 In Japan, there are few reports on coronary endothelial dysfunction.14,15

Inconsistency of Intracoronary ACH Testing in the Clinic

Physicians use intracoronary ACH testing to verify the presence of coronary spasm or coronary endothelial dysfunction. Low doses of ACH for 2–3 minutes’ continuous injection are used for the diagnosis of coronary endothelial function, while bolus injection of high-dose ACH for 20–30 seconds is used to investigate the presence of coronary epicardial spasm/coronary microvascular spasm.16 However, physicians may perform additional ACH testing arbitrarily (Tables 1–3). Furthermore, the majority of physicians do not perform vasoreactivity testing on both coronary arteries.7,16 They perform vasoreactivity testing mainly into the left anterior descending artery. If they obtain negative results for intracoronary ACH testing in the LCA, they then carry out intracoronary injection of ACH into the RCA whenever possible.

Duration of ACH Injection: 20 Seconds versus 180 Seconds

The duration of ACH injection plays an important role in the type of spasm provoked. Given the same doses of ACH in the same patients, rapid injection of ACH provoked more cases of epicardial spasm than moderate administration of ACH.17 Provoked spasm incidence by a 20-second injection of ACH was significantly higher than that by a 180-second ACH injection (73.3%, 22/30 versus 33.3%, 10/30, p<0.05).17 As shown in Figure 1, intracoronary injection of ACH for 20 seconds provoked typical epicardial spasm but that for 180 seconds did not (case 1), whereas in case 2, intracoronary injection of ACH for both 20 seconds and for 180 seconds produced the same coronary responses. Cardiologists should understand the clinical differences underlying the coronary responses between the two procedures, even in the same patients.

Transition for Ideal Vasoreactivity Testing of ACH

In 2014, Ong et al. reported on an incremental dose-up of 2 μg, 20 μg, 100 μg and 200 μg ACH manually infused over a period of 3 minutes into the LCA via angiographic catheter.18 The ACH doses in their protocol were derived from the multicentre ENCORE study (Supplementary Figure 1).2 In the ENCORE study, the dose for the left anterior descending artery and for the left circumflex artery was 100 μg into each vessel injected via selective catheter. For practical reasons, in the Ong et al. study the ACH injection was performed unselectively via the diagnostic catheter into the LCA with a maximum dose of 200 μg. In patients who remained asymptomatic and had no diagnostic ST-segment changes during LCA ACH infusion, 80 μg ACH was injected into the RCA.18 In the CASPAR study in 2008, incremental doses of 2 μg, 20 μg and 100 μg ACH were injected into the LCA via the diagnostic catheter for 3 minutes each.19 However, in 2016, Ong et al. reported the use of the same ACH doses with an injection duration of 20 seconds instead of 3 minutes without a pacemaker.20 The maximum ACH dose and the injection time in their study varied from 100 μg ACH to 200 μg ACH and from 3 minutes to 20 seconds, respectively.

In contrast, we performed intracoronary ACH testing from 1991 based on the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) guidelines.21 Incremental dose-up of 20 μg and 50 μg into the RCA and of 20 μg, 50 μg and 100 μg into the LCA was injected for 20 seconds with a pacemaker. We used a maximum ACH dose of 80 μg into the RCA from 1993, and a maximum ACH dose of 200 μg into the LCA from 2012.22

We have been performing intracoronary ACH testing for more than 30 years, but currently, there is no established global standard for ACH testing. Therefore, an important goal for the future is to establish optimum, unified recommendations for ACH testing for coronary spasm and coronary endothelial dysfunction.

Vasoreactivity Testing for Coronary Epicardial Spasm

The intracoronary injection time for ACH in Japanese reports is less than 30 seconds, while in the majority of Western reports it is over 3 minutes (Table 2).23–39 Furthermore, back-up pacing was necessary in Japanese reports, whereas in Western reports there was no back-up pacing during vasoreactivity testing of ACH. There are obvious methodological differences between Japanese and Western studies, and hence a unified method is needed to verify the presence or absence of coronary epicardial spasm. In the Western reports, if a positive epicardial spasm was not provoked in the LCA, intracoronary ACH was administered into the RCA. The main target coronary artery is the LCA for Western cardiologists, while Japanese cardiologists perform tests for both coronary arteries if possible. The definition of positive epicardial spasm was similar between Western and Japanese reports.

Vasoreactivity Testing for Coronary Microvascular Spasm

As shown in Table 3, the majority of researchers used the same methods to diagnose the presence or absence of epicardial spasm and coronary microvascular spasm.40 There are no recommendations regarding methodological issues in the COVADIS group 2017/18 reports.41,42 However, COVADIS reports in 2020 provided recommendations on ACH doses for the first time.10 They recommended intracoronary injection of ACH 100 μg into the LCA and ACH 50 μg into the RCA for 20 seconds without a pacemaker. Compared with Western reports, the ACH intracoronary injection time is remarkably short in Japanese reports. Back-up pacemaker insertion is necessary for ACH testing in Japan, while we could not find any mention of the procedure under pacemaker in Western reports.43 The definition of positive coronary microvascular spasm in Western reports is not different from that in Japanese reports.

Initial Examination: Physiological Functional Tests versus Vasoreactivity Testing

Western guidelines recommend coronary physiological functional measurements before vasoreactivity testing.9 However, Japanese physicians recommend vasoreactivity testing first, before coronary physiological functional measurements.43 Furthermore, Western cardiologists reported that the effect of intracoronary injection of <200 μg nitroglycerine had almost completely disappeared 10 minutes later, possibly due to the short half-life.44 If ACH testing is performed first, then resting flow and coronary flow reserve assessment may be inaccurate, particularly after a positive vasospasm test.17 However, JCS guidelines recommend at least 48 hours’ cessation of coronary vasodilators before coronary vasoreactivity testing. Western guidelines place considerable weight on the identification of coronary microvascular dysfunction, whereas Japanese researchers place importance on diagnosing the presence of epicardial spasm.

These methodological and ethnic differences may be contributing to the disparity in diagnostic strategies. Therefore, if the aim is to diagnose coronary epicardial spasm or coronary microvascular spasm, we suggest that ACH vasoreactivity testing be done first, before the assessment of coronary physiological functioning.

Need for Standardised Vasoreactivity Testing for Coronary Epicardial and Coronary Microvascular Spasm

Although there are ethnic and racial differences in epicardial spasm and coronary microvascular spasm, unified diagnostic testing worldwide is essential for patients with coronary vasomotor disorders, especially given that the definition of positive coronary microvascular spasm and of coronary microvascular dysfunction is not different between Western and Japanese reports. The challenge is, therefore, to establish a unified procedure for diagnosing epicardial spasm and coronary microvascular spasm.

Complications during Intracoronary ACH Testing

In the ENCORE II study, one patient died during intracoronary 3 minute ACH infusion for detecting endothelial function due to acute MI possibly related to ACH.45 Bradycardia has often been observed in Western reports, possibly due to the lack of back-up pacing, while the prevalence of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation is remarkably higher during ACH testing in Japanese reports (Supplementary Table 1). The occurrence of paroxysmal AF in Japanese reports is markedly higher than that in Western reports.18,22 Although we could not find a full list of the various complications in each report, there seem to be no irreversible complications during intracoronary ACH testing in the recent reports.18,32,37

Given that the COVADIS reports and the JCS guidelines recommend vasoreactivity testing as class 1, trained physicians can perform intracoronary ACH vasoreactivity testing without any complications. However, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines still recommend vasoreactivity testing as class 2b.46,47

Future Recommendations

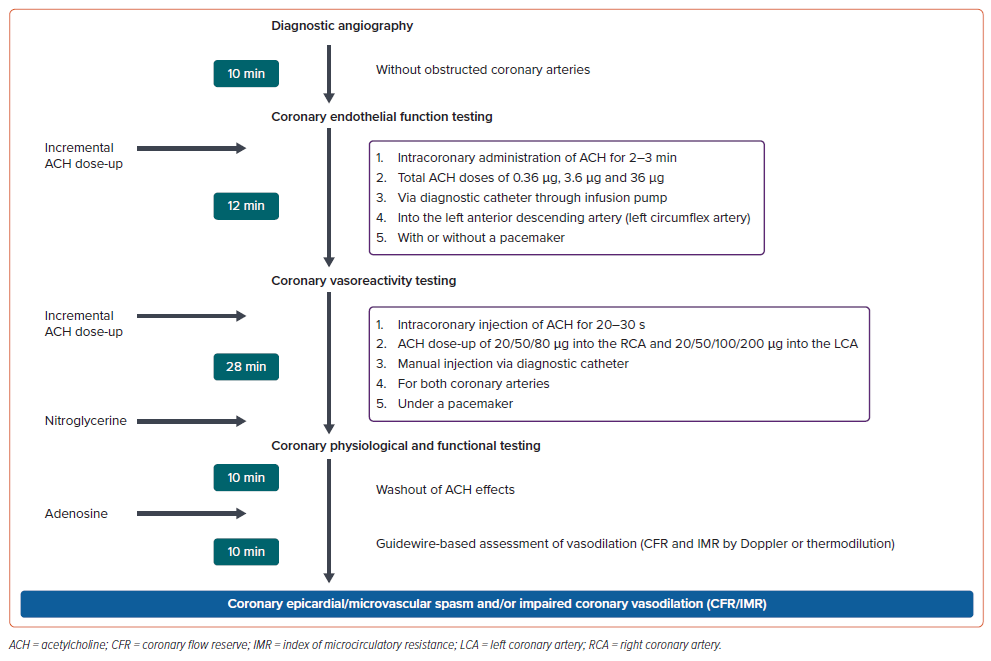

Global guidelines for the diagnosis of epicardial spasm, coronary microvascular spasm and coronary microvascular dysfunction are necessary, as are unified diagnostic strategies for use in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. As shown in Figure 2, the proposed ideal diagnostic interventional procedures may be cumbersome and time-consuming. A procedure time of approximately 1 hour is necessary to diagnose coronary spasm and coronary endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, radiation exposure and contrast medium due to repetitive coronary angiography are serious problems.

The cardiologist may perform culling vasoreactivity testing of ACH if patients have no coronary constriction after the injection of low-dose ACH. However, if cardiologists around the world perform this diagnostic interventional procedure carefully in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory, they may reach a satisfactory diagnosis for each patient.

Global guidelines should be established to unify the diagnosis of epicardial spasm, coronary microvascular spasm and coronary microvascular dysfunction, and the COVADIS, ESC, AHA/ACC, ACI-SEC (Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology) and JCS guidelines.

Conclusion

Vasoreactivity testing with ACH has two diagnostic functions: to identify coronary endothelial function and to investigate coronary microvascular spasm and epicardial spasm. However, each physician uses a different modified ACH protocol to diagnose epicardial spasm, coronary microvascular spasm and coronary endothelial dysfunction. Unified ACH testing for coronary spasm and endothelial function is, therefore, essential for cardiologists.