Clinical and economic benefits of fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided revascularisation have been established and the strategy is a class-1 recommendation in current guidelines.1,2 FFR values both before and after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have been reported to provide prognostic information.3–5

Originally, FFR was used as a surrogate measure of impaired coronary flow, and employed to compare flow without epicardial stenosis; the change in coronary flow before and after PCI could be evaluated, and minimum microvascular resistance under drug-induced vasodilation was assumed to remain constant. However, recent data have cast doubt on this presumption and indicate potential limitations of FFR in representing coronary flow change after PCI.6–9

In this article, we present our results about the relationship between changes in FFR and absolute coronary flow volume and discuss other recent studies examining this topic.

Methods

The present analyses were based on data from a recent report by our group. Changes in absolute coronary blood flow (ABF) and hyperaemic microvascular resistance (MR) after PCI were assessed using the thermodilution method.6 In brief, a small infusion catheter with a distal end-hole (3.9 Fr, Kiwami) was advanced over a pressure-temperature sensor-tipped guidewire, placed in the proximal portion of the coronary artery, and saline was continuously infused through the catheter. Pressure and temperature were continuously recorded using the guidewire, which was pulled back from distal segment into the infusion catheter. ABF and MR were calculated as follows:

ABF (ml/min) = 1.08 × (distal temperature)/(infused saline temperature) × (infusion rate of saline, 20 ml/h)

Hyperaemic MR = distal coronary pressure/ABF (dyne∙s∙cm−5)

Moreover, on the basis of FFR theory in which MR is constant during PCI procedure, we calculated the theoretically expected post-PCI ABF as follows:

Expected post-PCI ABF (ml/min) = pre-PCI ABF × post-PCI FFR/pre-PCI FFR

Delta ABF and FFR were defined as the post-PCI value minus the pre-PCI value.

We recruited 28 patients with stable angina who underwent PCI and ABF/FFR assessment both before and after PCI. Successful PCI was performed in all the patients and no periprocedural MI was documented. FFR was improved following PCI in every patient. We examined the association between: delta ABF and delta FFR; expected and measured post-PCI ABF and the difference between ‘expected and measured post-PCI ABF’; and changes in hyperaemic MR following PCI. The associations were measured by scatter plots and Pearson correlation coefficient using JMP 11.2.0 (SAS Institute).

Results

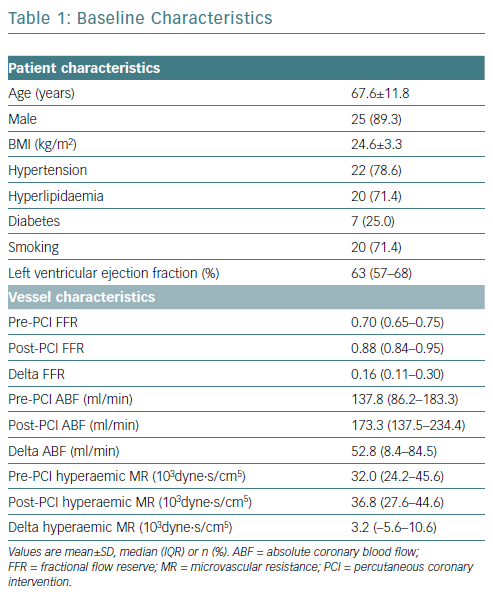

The present cohort had lesions and a median FFR of 0.70 (IQR 0.65–0.75). The mean age of the patients was 67.6 years (SD 11.8 years) and 89.3% (25/28) were male. Baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

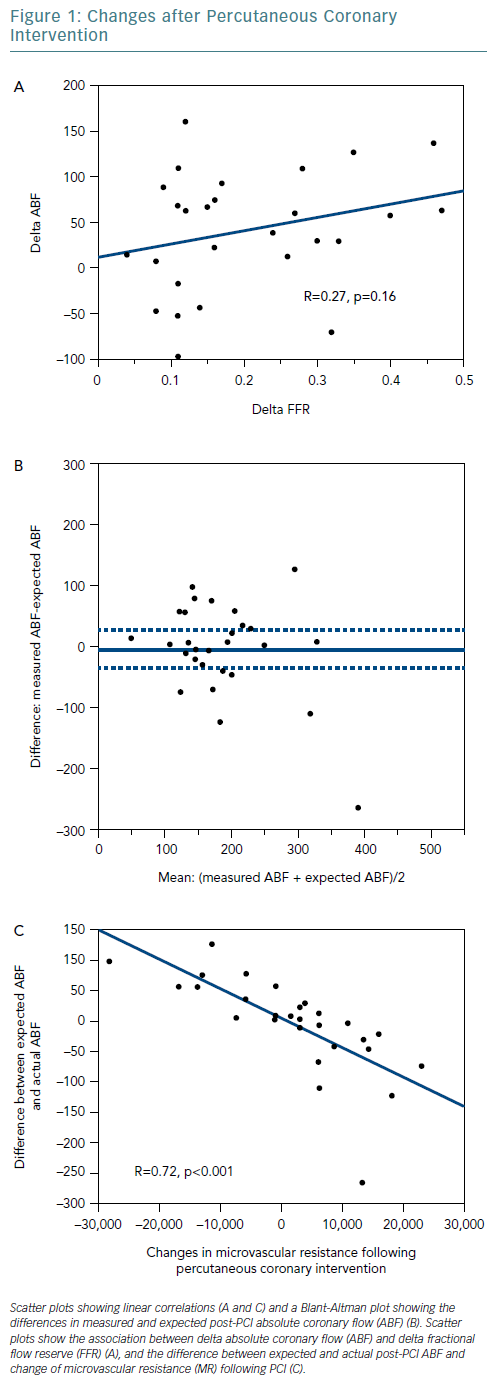

At cohort level, ABF significantly increased following PCI from a median 137.8 ml/min before to 173.3 ml/min after the procedure. However, at an individual level, six patients (21.4%) showed a decrease in ABF after PCI. The relationship between delta ABF and delta FFR was not significant (R=0.27, p=0.16) (Figure 1A). Delta ABF was widely distributed for lesions with delta FFR <0.2, which suggests that PCI might not necessarily improve coronary flow.

Figure 1B shows a Bland-Altman plot for measured and expected post-PCI ABF. Although the mean difference was −5.5 ml/min (measured ABF: 185.0 ml/min; expected ABF: 190.5 ml/min), the difference values varied greatly between individuals, and the 95% CI was relatively wide (−35.6–24.6 ml/min). Changes in FFR reflected changes in coronary flow well at a cohort level but poorly at an individual level.

Finally, we calculated the difference between expected and measured post-PCI ABF and compared the values with changes in hyperaemic MR following PCI (Figure 1C). The linear association was strong and robust (R=0.72, p<0.001). The results imply that coronary flow might decrease when hyperaemic MR increases following PCI.

Discussion

The present study provides evidence of the limitations of FFR in predicting absolute changes in coronary flow following PCI. Changes in MR might play a role in the discrepancy between changes in FFR and in absolute coronary flow.

Driessen et al. demonstrated a strong linear relationship between an improvement in FFR and an increase in myocardial blood flow, measured by serial PET examinations, following PCI.9 Their data are consistent with our study because strong relationships were observed especially in cases demonstrating high FFR improvement were likely to be associated with high myocardial blood flow improvement, and because changes in myocardial blood flow varied when the FFR was close to the grey zone. Another study investigating PCI-related changes in myocardial flow, which used phase-contrast cine cardiac MRI, also supports this observation.8 Importantly, these reports consistently demonstrate the phenomenon that PCI could result in a decrease in global myocardial blood flow.

These data suggest an important limitation of FFR as a surrogate measure for coronary blood flow, counterarguing the assumption that microvascular resistance under drug-induced vasodilation is constant from pre-PCI to post-PCI. Under the assumption, Ohm’s law suggests that the absolute blood flow should increase in all cases after PCI, since PCI increases distal coronary pressure as well as FFR value in almost all cases. The cases in which a decrease in coronary flow was documented imply that PCI that could potentially lead to an increase in microvascular resistance. The present study directly demonstrates this hypothesis by showing the relationship between the difference between the expected and actual post-PCI ABF and the change in microvascular resistance following PCI.

Change in coronary blood flow may be an important marker for evaluating the benefit of PCI. Several large randomised trials have shown the non-inferiority of optimal medical therapy to an invasive strategy.10 A double-blinded randomised trial demonstrated a non-significant efficacy of PCI in relieving patients’ symptoms.11 However, these studies did not evaluate PCI-related flow changes, and it is possible that the majority of these PCIs might not have resulted in coronary flow improvement. A recent meta-analysis showed an efficacy of FFR-guided PCI in reducing cardiovascular events.1 The result might be interpreted as evidence that the pre-PCI flow conditions were associated with the potential of flow improvement by PCI. Further studies are warranted to clarify the association between flow improvement and clinical outcomes.

Pre- or post-PCI FFR value in a continuous fashion is certainly one of the most important physiological markers. Changes in FFR can be correlated with coronary flow change in a cohort level; however, FFR alone could not accurately predict PCI-related flow change in individual patient levels.

An observational study suggested the potential utility of flow evaluation of another physiological index, coronary flow capacity, in addition to FFR.12 FFR is without doubt a clinically useful marker, but we need to recognise its limitations and explore other markers to support FFR in the prediction of individualised coronary flow improvement following PCI, and its relationship with the incidence of future cardiac events.

Limitations

This study prospectively, but not consecutively, included subjects from a single centre, making selection bias unavoidable. The current method for measuring ABF might not add any clinical value over FFR. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine coronary flow reserve by this method because direct saline infusion induces suboptimal hyperaemia. The reproducibility and inter/intra-observer variability of ABF or MR were not assessed. Other limitations are listed in our previous article.6

Conclusion

Changes in FFR following PCI do not necessarily indicate an increase in absolute coronary blood flow in individual patients, although they could be correlated at cohort level. This discrepancy might be explained by a change in microvascular resistance.