The definition of ‘fulminant’ myocarditis (FM) was first used in 1991 to describe an uncommon, severe form of biopsy-proven myocarditis that had cardiogenic shock (CS) with acute left ventricular failure as the initial presentation.1 The term FM is still used to define the most acute and life-threatening presentation of myocarditis, characterised by sudden onset and a rapid clinical deterioration in terms of left and/or right ventricular dysfunction, refractory ventricular arrhythmias and the need for pharmacological and/or mechanical circulatory support (MCS).2 In the past, however, although FM was considered a distinct clinical entity, robust evidence now shows that FM is, in fact, a clinical presentation of myocarditis and a marker of worse prognosis shared by different myocarditis types.3–6

No standardised definition of FM has been reported in the literature, and MCS has not always been used as a mandatory criterion for FM. Also, incessant ventricular arrhythmias (i.e. arrhythmic storm) are sometimes not taken into consideration, possibly leading to an underestimation of their severity in some studies.4 This discrepancy may account for the controversies about FM prognosis in the literature; now, its prognosis appears worse compared with non-fulminant forms, even in the long term.5–7 Given that FM is not a distinct form of myocarditis but a rare, aggressive clinical presentation that can be associated with different aetiopathogenetic forms, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is crucial for diagnostic work-up.8 The aims of this review are to describe the evolution of the definition of FM, to emphasise the importance of prompt and definitive aetiological diagnosis to guide treatment and to discuss updated evidence on FM prognosis.

Evolution of the Definition of Fulminant Myocarditis

From the first description of four cases of FM at the beginning of the 1990s, the definition of FM has varied greatly in the last 20 years, underscoring the lack of a standardised definition of FM that is significantly heterogeneous in published studies at different times.1 In 1991, Lieberman et al. proposed a clear-cut difference between FM and other (‘acute and chronic’) myocarditis forms based on EMB findings of four patients: FM was identified by more serious presentation (i.e. CS), different clinical course (i.e. complete recovery or death as natural history) and peculiar histological features (i.e. multiple foci of inflammation at diagnosis and complete resolution of inflammation at follow-up EMB).1 This first definition, despite having historical value, contained several inaccuracies. First, it considered only patients presenting with recent (up to 2 weeks) viral prodromal symptoms, which is now recognised as a possible but not mandatory clinical feature of myocarditis.9 Second, it used natural history (restitutio ad integrum or death) as a criterion to define FM, making it impossible to distinguish FM from other forms of myocarditis at onset. And last, it relied on a subjective evaluation of ‘severe’ versus ‘non-severe’ left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, with no clear cut-offs, introducing a bias in the classification of patients due to heterogeneous LV function evaluation methods by different observers.

In a previous study, Felker et al. reported that FM could be differentiated from other acute myocarditis forms by echocardiography: in FM the LV is not dilated and thickened, whereas in other forms of myocarditis the diastolic dimensions are increased and the LV septal thickness is normal.10 In 2000, McCarthy et al. also defined FM as a ‘distinct clinical entity’ from ‘acute myocarditis’ based on clinical findings.3 In that study, the authors proposed that FM was a disease with severe presentation and paradoxically good survival, while other myocarditis patients were initially less ill but frequently progressed to end-stage heart failure (HF) with either death or the need for heart transplantation (HTx). Importantly, that study considered only patients with lymphocytic myocarditis, excluding EMBs with different inflammatory infiltrates, especially eosinophilic myocarditis or giant cell myocarditis (GCM), which are now recognised as potentially presenting with a fulminant course and are often associated with an ominous prognosis. Moreover, patients with myocardial inflammation in the context of systemic immune-mediated diseases (SIDs), such as systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sarcoidosis or inflammatory bowel disease, were excluded. This may have produced a bias towards less severe forms of myocarditis, given that myocardial involvement in SIDs is now recognised as a marker of worse myocarditis prognosis.11

Even in recent years, some authors have described FM as an entity distinct from non-fulminant myocarditis.12 This is in contrast to the updated approach to myocarditis outlined in the 2013 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group Consensus Statement. Indeed, the updated classification of myocarditis is based on the confirmation of myocarditis at EMB (distinguishing clinically suspected from biopsy-proven myocarditis) and categorises life-threatening conditions (i.e. severe arrhythmias, aborted sudden cardiac death, CS and severe depression of LV function) as a possible presentation of myocarditis.9 Therefore, it appears clear that FM is a type of disease presentation that can be shared by different types of myocarditis and which needs to be carefully characterised by more than a pure clinical presentation pattern.

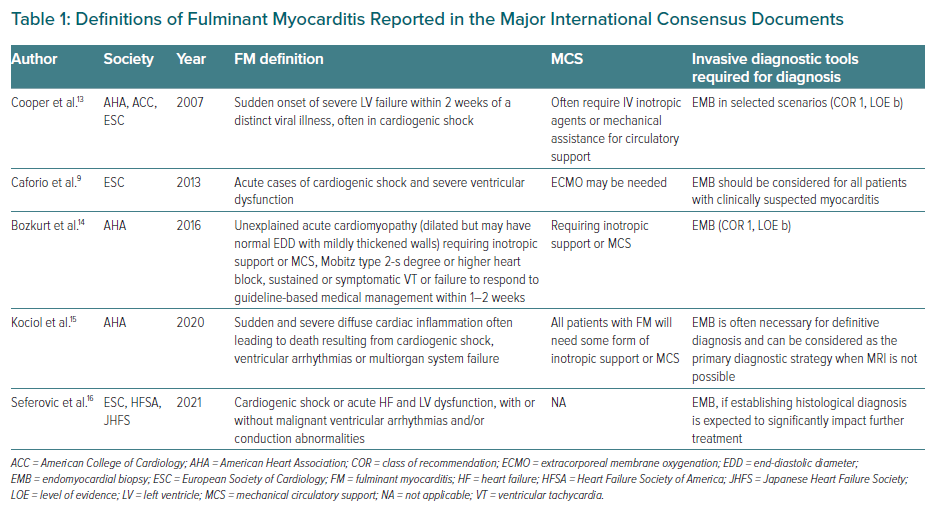

Table 1 summarises the main definitions of FM so far reported by the international consensus statements, outlining shared features but also clinical and diagnostic differences. A common feature of the different definitions is the timing of presentation, which needs to be ‘acute/sudden’ and which is almost always accompanied by CS and the requirement for inotropes and/or MCS. By analysing the evolution of the concept of FM from 2007 to 2021, it appears that FM is initially a ‘working diagnosis’ that should be postulated in an emergency setting as one of the causes of CS and/or arrhythmic storm. In keeping with this concept, the 2021 ESC Guidelines on HF recommend EMB as a diagnostic tool in the setting of rapidly progressive HF not responding to supportive therapy when there is a probability of a specific diagnosis, which can be confirmed only at histological examination.17,18 In a clinical context compatible with FM (i.e. young patient with no cardiovascular risk factors or after ruling out coronary artery disease by coronary angiography or CT coronary angiography), EMB should be considered to diagnose myocarditis (class 2a, level c recommendation). The guidelines also state that early identification of the underlying cause of acute decompensated HF is a key component of its management; in the case of FM, this seems particularly important given that specific types of myocarditis, such as GCM, eosinophilic myocarditis or cardiac sarcoidosis, which can be diagnosed based only on EMB findings, can present with a similar fulminant onset but require a targeted therapeutic approach without delay.18

The problem of the lack of a shared definition of FM demonstrates the difficulty of standardising the diagnosis of myocarditis irrespective of clinical presentation. While the role of EMB has been differently weighted by distinct authors in the past, strong evidence has recently been produced to support a histological diagnosis in the case of presumed FM. In 2007, Cooper et al. had already identified the crucial role of EMB for prompt diagnosis of FM in haemodynamically unstable patients (class 1).13 The 2013 ESC Working Group Consensus Statement extended these recommendations, stating that EMB should be considered for every patient with suspected myocarditis when clinically indicated.9 The same document also stated that myocarditis is a histologically defined disease, EMB being the only tool able to provide a diagnosis of certainty and to identify the underlying aetiological mechanism. Alternatively, only the definition of ‘clinically suspected myocarditis’ is possible based on coherent clinical, biochemical and instrumental data consistent with a presumptive diagnosis of myocarditis. In addition and beforehand, alternative diagnoses, such as coronary artery disease, should be ruled out. In 2016 Bozkurt et al. provided a class 1 recommendation for EMB in FM; the authors were also the first to suggest a timespan reference, describing FM as an unexplained acute cardiomyopathy complicated by either hypokinetic or hyperkinetic ventricular arrhythmia refractory to standard treatment in 1–2 weeks.14 This temporal criterion has been adopted by other authors.19 They differentiated myocarditis with fulminant (onset in 1–2 weeks) and non-fulminant onset (longer symptom onset at presentation), leading to conflicting results, especially in prognostic terms.5 In particular, McCarthy et al. included in their FM cohort patients who had undergone EMB to investigate HF or unexplained ventricular arrhythmias up to 12 months after symptom onset, which is not in accordance with an updated definition of FM.3

In 2020, the American Heart Association (AHA) Statement on Recognition and Initial Management of FM identified MCS as mandatory for FM definition; the authors state that EMB can be considered as a primary diagnostic strategy when MRI is not possible.15 Finally, in 2021, a position statement by the ESC, Heart Failure Society of America and Japanese Heart Failure Society concluded that EMB should be performed in myocarditis when the identification of histological diagnosis is expected to significantly impact further treatment, which seems to apply to most cases of FM.16

Histological Classification of Myocarditis Type

Here, we report an updated brief description of the histological classification of myocarditis.20 Each type of myocarditis can present with fulminant features. In addition, myocarditis histotype has an independent, crucial prognostic value, as outlined below.5,21

Lymphocytic Myocarditis

Lymphocytic myocarditis is the most common histotype of acute myocarditis, often associated with viral infections, autoimmune/connective tissue diseases or toxic agents.22 At a histological level it is characterised by a predominant myocardial patchy infiltration by T lymphocytes and macrophages. Cardiomyocyte necrosis or degeneration is present by definition according to the original Dallas criteria, and fibrosis may be absent or present.23 The presence of chronic inflammatory infiltrate in association with cardiomyopathic changes defines an entity called ‘dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with inflammation’ or ‘inflammatory cardiomyopathy’.24,25

Giant Cell Myocarditis

Giant cell myocarditis is characterised by extensive leukocyte infiltration with myeloid cell predominance (mainly macrophages, a difference with respect to other myocarditis forms in which T-cells are prevalent), and massive myocyte necrosis, in the absence of well-formed granulomas; eosinophils are also often present.20 Myocardial involvement is diffuse, which explains the high sensitivity of EMB.26–29 This disease has a poor prognosis: the reported rate of death or HTx is 48% at 5 years, and in survivors the progression to DCM is frequent; nevertheless, prompt specific treatment can improve the outcome.30,31

Eosinophilic Myocarditis

Eosinophilic myocarditis is indicated on histology by the presence of patchy, interstitial eosinophilic infiltrates. This form of myocarditis is often observed in systemic conditions associated with peripheral eosinophilia (e.g. primary idiopathic hypereosinophilia, hypersensitivity reaction to drugs or parasitic infections, allergic diseases and autoimmune disorders), but it may also appear as a primary isolated disease.32 Histological classification of myocardial hypereosinophilic syndrome identifies three stages of the disease: an acute phase with inflammation and necrosis, a thrombotic phase with subendocardial thrombosis, and a fibrotic stage with progression to restrictive cardiomyopathy (‘Loeffler’s endocarditis’).33

Cardiac Sarcoidosis

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown aetiology, commonly involving the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes.34 Cardiac sarcoidosis is characterised on histology by extensive infiltration by macrophages, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage with fibrotic replacement; eosinophils and necrosis are rare or absent.35 Differential diagnosis includes other forms of granulomatous myocarditis, such as mycobacterial infection.36 As cardiac sarcoidosis progresses, the granulomatous inflammation elicits a repair response with scarring, and fibrotic myocardium can become a substrate for malignant arrhythmias. Sarcoidosis affects the heart with a typical ‘patchy’ distribution, especially at the interventricular septum and LV basal free wall, and this accounts for the low sensitivity of EMB for its diagnosis.37

Role of Prompt Aetiological Diagnosis

Myocarditis is a rare cause of CS, with a reported incidence of 2% in all-cause CS (CardShock trial registry) and of 15% in non-ischemic CS.38,39 A recent US registry reported a significant increase in the incidence of CS in patients admitted for myocarditis, which almost doubled between 2005 and 2014 (from 6.94% to 11.99%), with a subsequent increased use of MCS in this setting.40

Similarly to other causes of CS, FM is a medical emergency that can have an extremely rapid progression and an ominous prognosis, with the need for prompt inotropic support or even MCS. Of the various short-term MCS options, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) has been traditionally used in emergency settings to stabilise FM patients with refractory CS; however, recent studies have noted that the LV afterload exerted by VA-ECMO may promote a vicious cycle by increasing myocardial inflammation.41,42 Therefore, LV venting and/or unloading strategies using other types of MCS, especially Impella, have been proposed as alternatives to enhance myocardial recovery (‘bridge-to-recovery’ strategy) due to their disease-modifying effects.43,44

As outlined in updated recommendations on CS, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for inflammatory cardiomyopathies as a cause of rapidly progressing acute HF.38,45–47 FM may develop at any age, without a prevalence in either gender, and each histological type of myocarditis (i.e. lymphocytic, eosinophilic, giant cell, sarcoid) may present with FM features.5,48 The key message that is endorsed by different statements is that patient survival depends on rapid recognition of the underlying cause of shock, which is the only way to establish an aetiological treatment for possible treatable causes. Given that myocarditis is a potentially curable disease, even in its most acute presentations, such as FM, its early recognition is crucial to ameliorate the natural history of the disease and improve prognosis.

In such an emergency clinical scenario, time is a key factor. By analogy to the concept of ‘time is muscle’ for coronary revascularisation in acute MI, several authors have proposed prompt referral of patients with suspected FM to hub centres with the ability to perform EMB and to offer both short- and long-term MCS to reduce mortality rate.4 This is due to the fact that histological and molecular data obtained by EMB have a strong probability of modifying outcomes because they can guide disease- or pathogen-specific management.17 EMB is also necessary to unmask what lies underneath the working diagnosis of FM, which is simply the description of a particularly severe clinical presentation of the disease. Therefore, EMB needs to be performed as soon as possible in the case of suspected FM; the procedure may be performed after ruling out acute coronary syndrome in the catheterisation laboratory at the same time as invasive coronary angiography.15 International guidelines recommend EMB as the primary diagnostic strategy for patients presenting with unexplained acute cardiomyopathy requiring inotropic support and/or MCS, severe hypo- or hyperkinetic arrhythmias and/or unremitting HF, all features of a presumptive diagnosis of FM.9,14,15 EMB has several aims, as outlined below.9,16,24

Confirmation of the Presence of Myocarditis

Myocarditis is a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, the diagnostic algorithm requires the investigation of other possible more common causes of myocardial injury, such as coronary artery disease.9 Clinically suspected myocarditis can be diagnosed by non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as cardiac MRI (CMR), which reaches relatively high rates of specificity and sensitivity when performed in a population with a high pre-test probability of myocarditis and following updated diagnostic criteria (i.e. 2018 updated Lake Louise criteria).49 However, T1- and T2-weighted CMR sequences may have a low sensitivity for diffuse myocardial oedema and fibrosis, such that the CMR sensitivity may vary depending on the clinical presentation of inflammatory cardiomyopathy, and the introduction of parametric mapping has been shown to partially overcome this technical issue.50,51 Nevertheless, in the context of CS, CMR is infeasible and should not delay EMB, which can be performed at the time of invasive coronary angiography following exclusion of an ischaemic cause of sudden cardiac failure.15 If EMB is negative, clinicians should consider alternative causes or even take into consideration the possibility of a sampling error, which is relevant in some remote yet ominous myocarditis types, such as cardiac sarcoidosis, for which, due to the patchy distribution of the disease, EMB sensitivity is only approximately 25%.11,52

Identification of the Histological Type of Inflammatory Infiltrate

Identification of the histological type of inflammatory infiltrate is relevant for prognosis and therapeutic implications.5,17,21 Non-invasive diagnostic tools (i.e. CMR) are clearly not capable of providing a histological description of the disease, although certain inflammatory heart diseases show particular findings on CMR (i.e. sarcoidosis, endomyocardial fibrosis), and lack the ability to characterise the type of inflammatory infiltrate. Thus, at least up to now, EMB is the only diagnostic tool providing an aetiological diagnosis, including rare or dangerous types of myocarditis, such as GCM, which must be promptly treated with aggressive immunosuppression.

The 2020 AHA Scientific Statement on FM clearly states that in GCM ‘delay in diagnosis is the major error in management.’15 On histology, GCM is characterised by diffuse or patchy inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes and eosinophils with multinucleated ‘giant cells.’ To achieve a steady control of the disease and extend the transplantation-free survival time, combination immunosuppressive therapy should be started as soon as possible.53–55 Therefore, for each patient presenting with clinical features of FM, GCM should be considered in the differential diagnosis and EMB should be strongly advocated to facilitate a definite diagnosis and start appropriate treatment without delay.

Exclusion of the Presence of Infectious Agents in the Myocardium

Viral genome search via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on EMB is crucial to establish appropriate therapy.9 Several studies have shown that high viral load and replicating viruses contraindicate the use of immunosuppression, while standing in favour of antiviral or immunomodulatory treatments (e.g. interferon).56,57 Debate has recently surged on the possible time-consuming aspect of waiting for PCR results for starting immunosuppression. A single retrospective study on 120 lymphocytic FM patients showed no difference in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events at 1 year after disease onset between patients who had EMB samples analysed for viral search and patients who did not; the authors suggested initiation of immunosuppression (e.g. steroid boluses) before PCR results.58 In any case, they stated that, after PCR results, initial immunosuppression (usually consisting of corticosteroids) may be stopped or modulated according to the results of viral search. Given that this study is the only one suggesting this approach, in the absence of prospective, larger controlled trials exploring the role of viral PCR in an FM setting, according to existing recommendations, PCR should be systematically performed.9,59

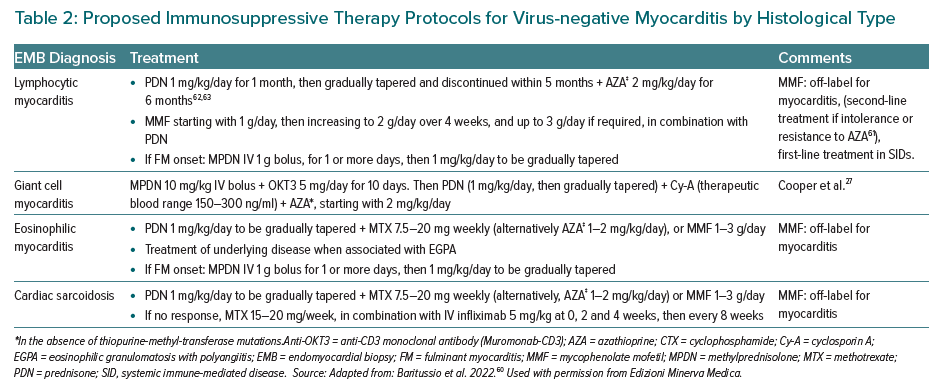

Current guidelines recommend the use of immunosuppressive therapy in selected patients with histologically confirmed autoimmune, virus-negative, myocarditis, particularly in cases of GCM, eosinophilic myocarditis or cardiac sarcoidosis.9,18 A brief description of the distinct immunosuppressive approaches for specific histological types of FM (i.e. lymphocytic, eosinophilic, GCM, cardiac sarcoidosis) is given in Table 2. Robust data have been produced in the form of randomised clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of histology-guided immunosuppression treatment of autoimmune virus-negative lymphocytic myocarditis, both in the short and in the long term, even in patients with poor baseline conditions (i.e. severe impairment of LV function) and for autoimmune myocarditis relapse; for other types of inflammatory cardiomyopathies (i.e. GCM, sarcoid or eosinophilic myocarditis), more data are needed to support a standardisation of immunosuppression protocols.62,63,18 Hence, the importance of the standardisation of immunosuppressive regimens, which need to be tailored not only to the disease features (i.e. histological type, severity of presentation) but also to the patient’s individual frailty profile.

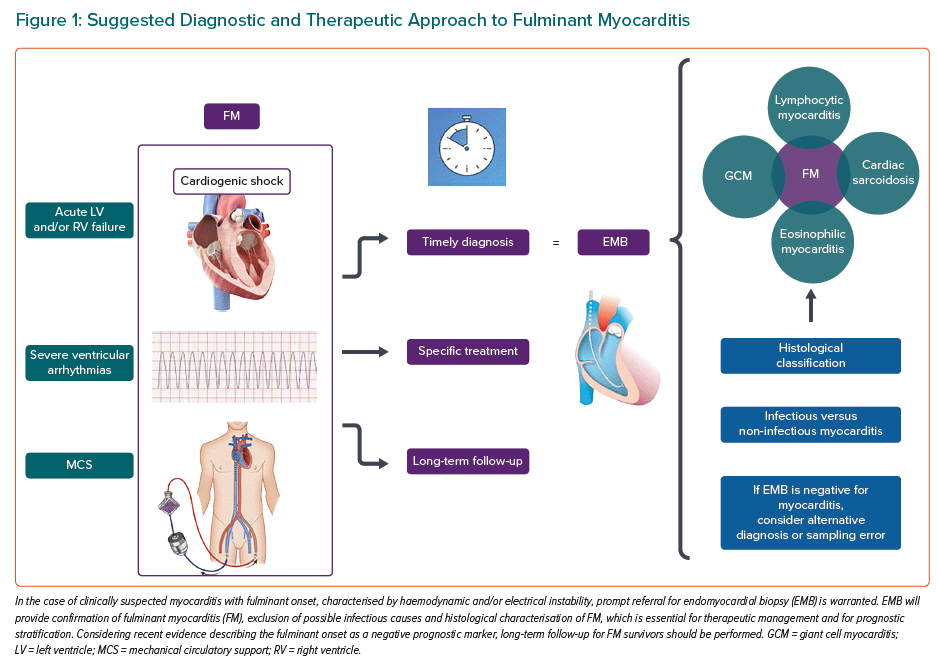

It is noteworthy that, even if in certain exceptional cases, therapeutic choices may be empirical, especially in settings that do not allow for an exhaustive and timely diagnostic assessment, strong evidence exists to show that the empirical approach to FM should not be standardised as routine practice.19 Therefore, a summary of a suggested diagnostic and therapeutic approach to FM is shown in Figure 1. Given that the EMB-guided approach to FM has recently been included in international guidelines, and the rate of EMB use seems to be low according to a 2018 US survey, this strategy should be implemented in clinical practice.16,18,64 According to the most recent international consensus statement on EMB, the procedure is associated with a low rate of major complications (~1%), and in particular with a low risk of mortality (0–0.07%), especially in high-volume centres and when performed by experienced operators.16 Of the major complications, cardiac tamponade due to myocardial perforation is more frequently reported in the case of right-sided EMB, and its treatment is immediate pericardiocentesis; conversely, left-sided EMB can be more frequently complicated by stroke or systemic embolism, the risk of which can be diminished by non-invasive screening for intraventricular thrombus and intraprocedural use of low-dose heparin if high thromboembolic risk is detected.

Controversies in Prognostic Stratification

Until recently, it was incorrectly believed that FM had a paradoxically low rate of mortality after the resolution of the acute phase of the disease, with a reported recovery rate of 50–70%.65 In 2007, a statement on EMB by the AHA, the American College of Cardiology and the ESC stated that ‘adults and paediatric patients who present with the sudden onset of severe left ventricular failure within 2 weeks of distinct viral illness and who have typical ‘lymphocytic’ myocarditis on EMB have an excellent prognosis.’13 In contrast, robust evidence has been produced in recent years to show that relevant biases in prior studies led to erroneous considerations of FM, especially regarding the outcomes.66 Until the early 2000s it was believed that early instauration of advanced HF therapies such as ECMO support could result in improved prognosis by preventing multiorgan failure while the acute inflammatory process in the myocardium was spontaneously healing.67 In other words, aggressive short-term haemodynamic support was believed to be sufficient to treat a disease that, once healed, would disappear forever without major sequelae.68

Notably, these studies involved a low number of patients, did not report long-term outcome, included a relevant proportion of patients with clinically suspected myocarditis and, when EMB was performed, did not provide a detailed histological diagnosis of FM, or exclude infectious causes of myocarditis (Supplementary Material Table 1).1,3,69–75 Moreover, only a few published studies investigated the role of immunosuppression or viral eradication therapy in biopsy-proven FM, which could potentially play a strong role as a modifier of the natural course of the disease.9

Notably, updated evidence has demonstrated a strongly negative prognostic value for fulminant presentation in terms of large single-centre studies or meta-analysis.41,76 A profound change of perspective was offered by Ammirati et al., who in 2017 published a study on 187 FM patients, mainly with clinically suspected myocarditis, with a 9-year follow-up; in that study, the FM patients had lower mortality- and HTx-free survival than patients with non-fulminant myocarditis, and had persistently lower LV ejection fraction (LVEF) during follow-up.4 In particular, FM patients surviving the acute phase of the disease were more likely to have reduced LV function at discharge compared with other types of myocarditis presentation, even if a relevant improvement was observed in the acute phase (29% of FM patients had LVEF < 55% at last follow-up versus 9% of non-FM patients). This is in keeping with recent findings that confirm LVEF as one of the most important factors for long-term prognosis in myocarditis.6,77 These findings are clearly in contrast to the concept that FM could have a favourable long-term prognosis.

Ammirati et al. explain the discordant results of previous studies by the use of different inclusion criteria and a possible selection bias towards less serious forms (i.e. exclusion of patients with severe disease who had already died before inclusion).4 These findings were corroborated by a subsequent international multicentre cohort study of 220 myocarditis patients with systolic dysfunction, of whom 165 had fulminant presentation, all with histological diagnosis.5 The main finding of that large study was that fulminant presentation of myocarditis was the major determinant of both short- and long-term prognosis. Moreover, another recent study of 466 EMB-proven or clinically suspected myocarditis patients confirmed that fulminant presentation is an independent risk factor for death or HTx in the long term, as well as female gender, young age, and high-titre anti-heart and anti-nuclear autoantibodies, suggesting that FM due to an autoimmune form will have a distinctively worse prognosis if untreated.6 These findings support the need for long-term follow-up of FM survivors, who have a higher risk for adverse cardiovascular events even long after disease onset.

To date, a single case of recurrent immune-mediated virus-negative lymphocytic FM has been reported, the first occurrence presenting with acute LV failure and the second, with arrhythmic storm, highlighting the remote but possible occurrence of FM relapse in the same patient, particularly when due to an autoimmune mechanism.78 Disease recurrence is indeed a known feature of all autoimmune diseases.79 Finally, some specific forms of myocarditis with fulminant presentation may deserve prolonged immunosuppression, such as GCM, the prototype of autoimmune myocarditis, which may recur even in the transplanted heart, requiring dedicated follow-up in highly specialised centres.58,80

Conclusion

FM is a type of clinical presentation of myocarditis that should always be considered as a differential diagnosis in the setting of sudden-onset CS and/or arrhythmic storm. In this clinical setting, prompt diagnosis is key to enabling specific treatment. A targeted and rational therapeutic approach to severe, life-threatening forms of inflammatory cardiomyopathy is crucial for patient survival and deserves histological and aetiological definition: this is why early referral for EMB is warranted. This approach has recently been included in the recommendations of the international guidelines and should be implemented in clinical practice. FM survivors have a worse prognosis than non-fulminant myocarditis patients, particularly those with non-infectious autoimmune forms, and should receive long-term follow-up in dedicated centres.