Erectile dysfunction (ED) is generally defined as the persistent (at least 6 months) inability to achieve and maintain penile erection sufficient to allow satisfactory sexual performance.1 It is a common condition, and recent studies predict a higher prevalence of ED in the future.2 It is estimated that ED has affected more than 150 million men worldwide and this number will reach approximately 322 million by 2025.2,3 It has affected 30 million men in the US alone.4

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD), also known as coronary artery disease (CAD), is a predominant manifestation of cardiovascular disease (CVD). CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for 17.3 million deaths globally every year; this figure is expected to grow to 23.6 million by the year 2030. Eighty per cent of these deaths occur in lower- and middle-income countries.5 ED and IHD are highly prevalent and occur concomitantly because they share the same risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and smoking.

The incidence of ED is 42.0–57.0 % in men with CAD and 33.8 % in those who have diabetes with silent ischaemia, compared with 4.7 % in men without silent ischaemia.6 The prevalence of ED is likely to be higher than the reported figures, because men generally do not seek medical advice for ED.6 Erection is thought to be a process that is regulated by hormones and neurovascular mechanisms in cerebral and peripheral levels.7

Causes of ED may be of primary developmental origin or secondary. Lack of sex hormone in the early developmental stage of male children is the major cause of primary ED. The secondary cause of ED involves arteriosclerosis, diabetes or psychogenic disturbances. Other secondary factors may include hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and tobacco use. The primary causes of ED are beyond the scope of this review; we will not be discussing the neurovascular mechanisms pertaining to ED and will focus on the relationship between IHD and ED.

Association Between ED and IHD

The association of ED and IHD has been a constant matter of study. Many previous studies have documented that IHD and ED are linked. IHD can be used to predict the risk of ED because both conditions have the same risk factors. Conversely, ED may trigger events that further lead to IHD.

ED is generally associated with significant changes in established cardiovascular risk factors. Atherosclerosis is the main cause of ED development in both the general population and patients with diabetes. However, the prevalence of ED is greater in patients with diabetes than in the general population.8 ED has been shown to occur at rates as high as 50 % in patients with CAD.9 A meta-analysis of 12 prospective cohort studies has provided evidence that ED is a predictor of IHD associated with an increased risk of CVD, stroke and all-cause mortality.10

Previous studies reported that there is a strong chance of future cardiac events when ED occurs in younger men compared with older men.11 Another study suggested that there is consistent association across age groups.12 A study of men with diabetes found that ED acts as an indicator of cardiovascular events after adjusting for other illnesses, psychological aspects and the usual cardiovascular risk factors.13 Another large-scale study comprising 25,650 men with pre-existing ED suggested that these men had a 75 % increased risk of peripheral vascular disease.14 Moreover, some studies demonstrated a relationship between ED score and number of diseased coronary arteries and plaque burden in coronary arteries.2,15

A study that examined the association between ED and asymptomatic CAD showed that 67 % of patients had ED for a mean 38.8 months before developing symptoms of CAD.16 Interestingly, all patients with type 1 diabetes in this study had ED well before symptoms of CAD.

Artery size also explains the onset of ED before occurrence of CAD. Coronary arteries are 3–4 mm in diameter, while the penile artery is 1–2 mm in diameter.17 Endothelial dysfunction and plaque burden in the small arteries may cause symptoms of ED before they affect blood flow in large arteries. Also, an asymptomatic lipid-rich plaque in the coronary arteries carries the risk of rupture that leads to acute coronary syndrome or death, so ED may be predictive of these serious events without warning cardiac symptoms.17

Some commonly prescribed cardiovascular drugs (beta-blockers, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, etc.) contribute to ED.18 Previous studies have shown a strong association between ED and diuretics in patients treated with hydrochlorothiazide or chlorthalidone.19,20 It has also been shown that patients treated with first-generation non-selective beta-blockers, such as propranolol, had more frequent ED than those treated with a placebo.21

Second-generation cardioselective beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol, etc.) can also lead to ED. Atenolol was shown to cause significant reduction of sexual activity compared with placebo in a double-blind, parallel-arm study.22 The same study also showed a significant reduction in testosterone levels with atenolol versus valsartan. An open, prospective study of hypertensive men treated with atenolol, metoprolol and bisoprolol for at least 6 months showed high prevalence of ED – approaching 66 % – in these patients.23

The impact of third-generation cardioselective beta-blockers such as carvedilol and nebivolol has also been investigated. Fogari et al. investigated the effect of carvedilol on erectile function in a double-blind crossover study involving 160 men newly diagnosed with hypertension and found chronic worsening of sexual function in those treated with carvedilol compared with valsartan and placebo.24

Nebivolol seems to have an advantage over other beta-blockers when used to treat men with hypertension and ED. It has additional vasodilating effects because it stimulates endothelial release of nitric oxide (NO), resulting in relaxation of smooth muscle in the corpus cavernosum, allowing penile erection.25 Despite limited studies, nebivolol does not seem to worsen erectile function and some studies have demonstrated significant improvement in erectile function with nebivolol compared with second-generation cardioselective beta-blockers.23,26–28

Most studies into the effect of beta-blockers on ED point to negative effects of first- and second-generation beta-blockers, while beta-blockers with vasodilating effects can improve erectile function. Alpha-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors seem to have a neutral effect on erectile function. Multiple previous studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of angiotensin receptor blockers on erectile function and they should probably be the favoured antihypertensive agents in patients with ED.29

Aetiology

In most men, ED is recognised as sharing vascular aetiology with IHD.17 ED and IHD share common risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, obesity, lack of physical exercise, cigarette smoking, poor diet, excess alcohol consumption and psychological stress, including depression.30 Endothelial dysfunction has been implicated as a common mechanism between CAD and ED and it has an important role in the development of atherosclerosis.31

The role of endothelial dysfunction in CAD is well known.32,33 Also, endothelial-derived NO induces vasodilatation, which in turn is an important event to achieve normal erectile function.34–36 Moreover, systemic endothelial-dependent vasodilatation has been shown to be reduced in men with ED.37,38

Risk Factors

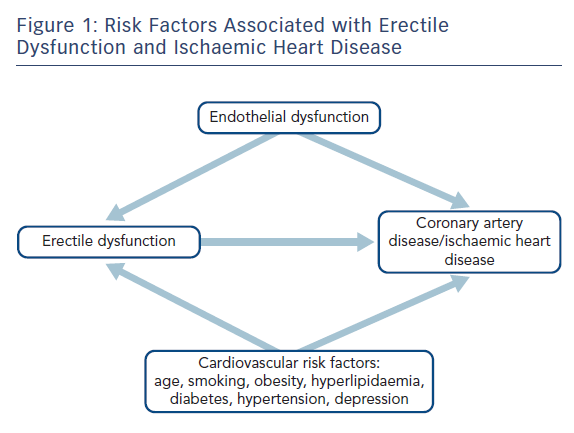

ED and IHD share the same risk factors (Figure 1). Endothelial dysfunction is the common link between ED and IHD.5

Age

Age is a critical risk factor for the development of ED and endothelial dysfunction.4,5 ED is the most common condition occurring in middle-aged and older men.5 Kinsey et al. reported that 25 % of 65-year-old men and 75 % of ≥80-year-old men have ED.39 Moreover, ageing also decreases endothelial function, which is responsible for IHD.5 The incidence and severity of ED increases with age (a man aged 70 years is three-times more likely to have ED than a man aged 40 years).40

Blood Pressure

Hypertension can affect endothelial function in many ways. It can reduce endothelium-dependent vasodilatation by increasing the vasoconstrictor tone as a result of increased peripheral sympathetic activity.41–43 Another mechanism is hypertension-induced increase in cyclooxygenase activity that leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species; these in turn damage endothelial cells and disrupt their function.44–46 In some cases, endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) gene variations may relate to hypertension-associated endothelial dysfunction.6

Cholesterol

High cholesterol level is an independent risk factor for ED. A 22-month follow-up study estimated that each mmol/l increase in baseline total cholesterol level increases the risk of ED by 1.32 times.4 In a study by Seftel et al., 42 % of men with ED also had hyperlipidaemia.47 In another study, 114 patients with ED had elevated LDL cholesterol.48

Smoking

Smoking is an independent risk factor for ED. Tobacco smoking causes direct toxicity to endothelial cells, including decreased eNOS activity, increased adhesion expression and impaired regulation of thrombotic factors.6 A meta-analysis of 19 studies by Tengs and Osgood suggested that 40 % of the impotent men studied were current smokers compared with 28 % who had never smoked.49

Obesity

Obesity is a strong predictor of ED as it is associated with other risk factors, such as diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and hypertension.4 Obesity increases the risk of ED by 30–90 % and acts as an independent risk factor for CVD. Obese men with ED have greater impairment in endothelial function than non-obese men with ED.5 Moreover, high BMI causes low testosterone levels, which in turn leads to ED, as observed in a prospective trial involving 7,446 participants.50

Psychological

A considerable number of patients with ED can have psychogenic factors as the only cause, or in combination with organic causes of ED. Depression, low self-esteem and social stresses are among the psychogenic factors that can lead to ED. Depression is an independent risk factor for both ED and IHD; these three disease conditions are interlinked.51 Psychogenic ED can be managed by multiple psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, couples counselling and guided sexual stimulation techniques.52

Diabetes

ED is a common complication of diabetes and people with diabetes are also prone to developing cardiovascular complications.48 The risk of ED is relatively high in patients with known CVD. This was supported by a study of men with known CVD, in which ED was substantially predictive of all-cause mortality and the composite of CVD death, admission for heart failure, MI and stroke.17 Macroangiopathy, microangiopathy and endothelial dysfunction are among the mechanisms by which diabetes causes ED.

Subnormal testosterone levels have also been observed in patients with diabetes and this is thought to be either autoimmune or a result of low levels of sex hormone binding globulin secondary to insulin resistance.53

Pathophysiology of Erectile Dysfunction and Ischaemic Heart Disease

Normal penile erection is controlled by two mechanisms: reflex erection and psychogenic erection. Reflex erection occurs by directly touching the shaft of the penis, while psychogenic erection occurs by erotic or emotional stimuli. ED is a condition where erection does not take place by either mechanism. ED can occur because of hormonal imbalance, neural disorders or lack of adequate blood supply to the penis.54 Lack of blood supply can be a result of impaired endothelial function associated with CAD.54

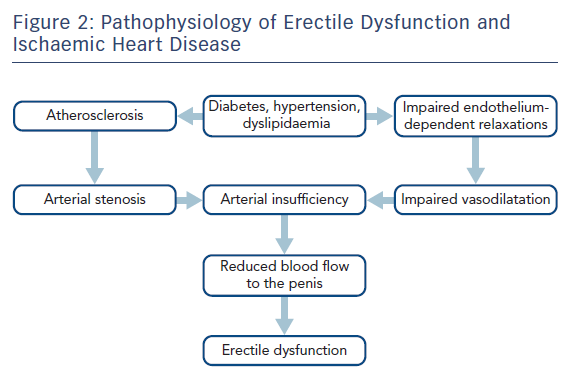

The vascular endothelium has an important role in angiogenesis and vascular repair by producing regulatory substances, including NO, prostaglandin, endothelins, prostacyclin and angiotensin II. These regulatory factors regulate the blood flow to the penis by controlling smooth muscle contractility and subsequent vasoconstriction and vasodilatation. Generally, in erectile tissue, increased blood flow through the cavernosal artery increases shear stress and produces NO, which further relaxes the vascular smooth muscles and increases blood flow in the corpora cavernosa.54 These events cause penile erection. However, in ED, endothelial NO synthesis is reduced and there is increased endothelial cell death (Figure 2).55

Myocardial ischaemia is caused by the reduction of coronary blood flow as a result of fixed or dynamic epicardial coronary artery stenosis, abnormal constriction or deficient relaxation of coronary microcirculation, or because of reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.56 Atherosclerosis is the major cause of myocardial ischaemia. Plaque that develops in atherosclerosis can rupture causing platelet aggregation and subsequent thrombus formation, which leads to MI. The other mechanisms of myocardial ischaemia are encountered far less than atherosclerosis. Endothelial dysfunction has an important role in the progression of atherosclerosis. Endothelial dysfunction enhances the intimal proliferation and malregulation that results in plaque destabilisation in the arteries.6 This process, coupled with paradoxical vasoconstriction, can result in major cardiovascular events such as MI.32

Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction in Men with Ischaemic Heart Disease

The third Princeton Consensus (Expert Panel) Conference recommends assessing cardiovascular risk in all patients with ED and CVD. This refers to estimating the risk of mortality and morbidity associated with sexual activity. The current recommendations classify patients into low-, intermediate- and high-risk, based on their New York Heart Association class.57 The consensus also recommended that all patients with ED and CVD should undergo lifestyle changes, such as exercise, smoking cessation, healthy diet and weight reduction. These measures are likely to reduce cardiovascular risk and improve erectile function.58

Patients with ED at high risk of cardiovascular events should refrain from sexual activity until they are stable from a cardiovascular point of view. Their management should be under close supervision from a cardiologist.58

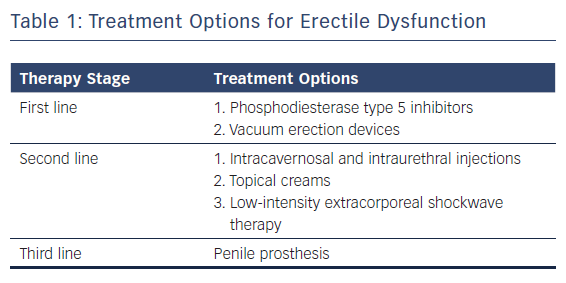

PDE5 Inhibitors

Guidelines recommend that phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors are the first-line drug for the treatment of ED (Table 1). Sildenafil citrate was the first oral drug approved for ED in the US.59 The newer PDE5 inhibitors include vardenafil, tadalafil and avanafil. The inhibition of PDE5 enhances cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-NO-mediated vasodilatation by preventing PDE5 catabolism of cGMP and so delaying detumescence. PDE5 inhibitors increase the number and duration of erections, as well as the percentage of successful sexual intercourse.60

PDE5 inhibitors are commonly prescribed to treat ED. The second Princeton Consensus Conference reviewed their appropriate use and recent studies of placebo-controlled and post-marketing surveillance data have confirmed their safety regarding cardiovascular events.61–63

Olsson et al. conducted a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, and flexible dose study in 224 men with ED and one CVD, including IHD (20 %) and hypertension (80 %). This study reported that the sildenafil-treated group showed 71 % improvement in ED compared with the placebo-controlled group (24 %).64 Furthermore, no treatment-related cardiovascular adverse events were reported.65 Conti et al. showed in an early study that sildenafil is an effective treatment for ED in patients with IHD; the majority of patients reported improvement in penile erection with it.66 Another double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients with ED and stable CAD showed statistically significant improvement with sildenafil versus placebo in both the frequency of penetration and frequency of maintained erections after penetration.67

However, sildenafil should be used carefully with nitrates because their combination can result in severe hypotension and death.68 Both short- and long-acting nitrates are commonly prescribed to treat angina, but they have no prognostic benefit. In addition, there are numerous alternatives to treat angina, such as ranolazine and ivabradine, which do not interact with PDE5 inhibitors. As a result, patients with ED wishing to take PDE5 inhibitors can safely discontinue their nitrates and replace this treatment with the other anti-anginal agents.68

The safety of PDE5 inhibitors in patients with IHD has been shown in multiple trials. Arruda-Olson et al. investigated the safety of sildenafil during exercise stress tests in patients with IHD to ascertain whether the drug induces or exacerbates myocardial ischaemia. This was a prospective, randomised crossover study that demonstrated safety of sildenafil when given 1 hour before an exercise stress test.69 Another study that investigated 120 trials of sildenafil revealed that the rates of MI and cardiovascular death with sildenafil are as low as with placebo.70

The recommended dosage of sildenafil is 50 mg/day, usually taken 1 hour before sexual activity. This dose may be increased to 100 mg or decreased to 25 mg based on side effects.6 PDE5 inhibitors also have a beneficial effect in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction as well as pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension. The use of PDE5 inhibitors in the treatment of right heart failure and left ventricular failure associated with combined pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension has been well studied.71,72

Vacuum Devices

Vacuum erection devices are an effective first-line treatment for ED, regardless of the underlying cause. They can be used in combination with PDE5 inhibitors and they have high reported satisfaction rates. They are generally well tolerated, with minor adverse effects such as bruising, pain and failure to ejaculate.73

Testosterone

It is recommended that testosterone be measured in patients with ED because low levels are a reliable measure of hypogonadism. Hypogonadism is not only a treatable cause of ED, but can also lead to reduced or lack of response to PDE5 inhibitors.73 Testosterone deficiency is also associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.74 Levels >350 ng/dl do not usually require replacement, but in patients with testosterone <230 ng/dl, replacement can usually be beneficial.57 In patients with congestive heart failure, testosterone replacement can lead to fluid retention, so caution is advised. In these patients, the aim should be to keep testosterone levels in the middle range, i.e. 350–600 ng/dl.57

Testosterone cypionate and testosterone enanthate injections are used for replacement therapy in patients with low testosterone. Other formulations, such as gels and patches, are recommended in older patients with chronic conditions.57 Serum prostate specific antigen should be measured before starting testosterone replacement, then 3–6 months after starting the treatment, followed by annual measurement.74

The benefits of testosterone replacement and the potential cardiovascular risks need to be thoroughly investigated, ideally through randomised controlled trials.

Other Therapies

Intracavernosal and intraurethral injections are second-line therapy for patients with ED. Alprostadil is the agent most commonly used for intracavernosal injections. The main adverse effects of intracavernosal injections are painful erection, priapism and development of scarring at the injection site.73 Alprostadil is also available as a topical cream in patients who cannot tolerate injections.75

Another injection option is the combination of phentolamine and aviptadil. This is effective, but requires simultaneous sexual stimulation to achieve its desired effect.73 Side-effects include headache, facial flushing and, rarely, tachycardia and palpitation.73

Intraurethral prostaglandin E1 pellets are suppositories that are inserted into the urethra. These agents act by relaxation of cavernous smooth muscle, which elevates the intracavernosal cGMP and by blocking the local alpha-receptors, resulting in improved erectile function.2

Another second-line treatment is low intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy. This can be very useful, especially in patients who failed oral therapy, but do not wish to start injections.73

Penile prosthesis is recommended as third-line treatment for patients who are fit for surgery and intolerant of oral medication, injections or external device therapy. A penile prosthesis is particularly useful in patients with severe organic ED, achieving long-term effects and high satisfaction rates without the need for further medication.73

Future Treatment Options

Gene therapy has the potential to become a future management option for patients with CAD and ED. Animal studies have been conducted to evaluate the effects of gene therapy. A rat model was studied by Bivalacqua et al. to evaluate the effect of the combination of eNOS gene therapy and sildenafil. This research suggested that erectile response was greater in male rats with diabetes treated with combination eNOS gene therapy and sildenafil, compared with male rats with diabetes treated with eNOS gene therapy or sildenafil alone.76–78

Stem cell therapy is an attractive treatment modality and an appealing option for tissue regenerative therapy for ED. Stem cells are pluripotent cells that can be produced from multiple regions within the body. They have the potential to divide and differentiate into numerous kinds of human cells, such as endothelial cells and smooth muscle.79 The efficacy and safety of gene and stem cell therapy in patients with ED and IHD need to be extensively investigated because both seem to have the potential to correct underlying abnormalities in ED. This would be a huge development in terms of management options for patients with ED and IHD.

Conclusion

ED is a common disease affecting men with IHD. Endothelial dysfunction is the link between ED and IHD and both diseases share the same aetiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. Aggressive control of these risk factors – along with lifestyle modification – is recommended to improve symptoms of ED and reduce cardiovascular risk. PDE5 inhibitors remain the first-choice treatment for ED in IHD patients and they have been shown to be safe and effective. However, PDE5 inhibitors can potentiate the hypotensive effect of nitrates so concomitant administration of sildenafil and nitrates is contraindicated. Gene and stem cell therapy are being investigated as a future therapies for ED.