Dyspnoea is one of the most distressing and debilitating symptoms experienced by oncological patients, usually in association with fatigue, anxiety and depression. It is also disturbing and upsetting to family members, leading to functional limitations in patients and a compromised quality of life (QoL) for both patients and caregivers.

Definition of Dyspnoea

The term ‘dyspnoea’ comes from two Greek words: dus (difficult) and pnoe (breathing), meaning laboured breathing. Synonyms of dyspnoea include shortness of breath, breathlessness, gasping and air hunger. The American Thoracic Society defines dyspnoea as ‘a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity’.1

Dyspnoea is a multidimensional, subjective symptom with physiological, psychological, environmental and social components and several potential underlying pathologies. It affects QoL critically and is one of the most common symptoms that leads patients to the emergency department.

Incidence of Dyspnoea in Cancer

In the emergency room, 3.3% of patients presenting with dyspnoea have a malignancy.2 Dyspnoea is the fourth most common symptom in oncological patients, with an incidence of 21–90%, and the fifth most prevalent symptom, with moderate to high severity in outpatient oncological patients (19.1%), after tiredness (40.3%), weakness (37.9%), pain (25%) and a lack of appetite (22.3%).3

It is more common in patients with lung cancer, affecting up to 75%, and in those with advanced cancer (10–70%).4,5 Dyspnoea intensifies with disease progression, with 70–80% of patients with terminal-stage cancer experiencing dyspnoea at some point during the last 6 weeks of life.6

Impact of Dyspnoea in Cancer

Dyspnoea is the most distressing symptom multidimensionally, as it can be refractory and harrowing for oncological patients and their caregivers, impairing quality of life (QoL), and depriving patients of the ability to participate in desired activities and be physically functional.7,8

Psychologically, it leads to anxiety, panic, hopelessness, helplessness, depression and social isolation.9

Equally important is the prognostic value of dyspnoea in cancer patients, especially at rest. In advanced cancer, it portends poor prognosis with life expectancy of less than a few months with implications for treatments and palliative options.

Types of Dyspnoea in Cancer

Dyspnoea can be present at rest or exertion and, depending on its onset, acute or chronic (present for >1–2 months). A more contemporary distinction between types of dyspnoea is:

- Episodic or breakthrough dyspnoea: intermittent, time-limited episodes of dyspnoea (seconds to hours) that occur with or without underlying continuous breathlessness. Episodes may be predictable or unpredictable, depending on whether possible triggers have been identified;10 and

- Continuous, constant or background dyspnoea: dyspnoea is present for most hours of the day.

Another term, which was added recently to the literature by an international consensus, is ‘chronic breathlessness syndrome’; this is defined as shortness of breath that persists despite optimum treatment for the underlying pathophysiology and results in disability.11

‘Dyspnoea crisis’ is defined by the American Thoracic Society as sustained, severe resting breathing discomfort that occurs in patients with advanced, often life-limiting illness and overwhelms patients’ and caregivers’ ability to achieve symptom relief. Dyspnoea crisis can occur suddenly and is characteristically without a reversible aetiology.12

‘Terminal dyspnoea’ is another contemporary term and describes dyspnoea in patients with an estimated life expectancy of weeks to days.13

Causes of Dyspnoea in Cancer

Causes of dyspnoea can be multifactorial in oncological patients.

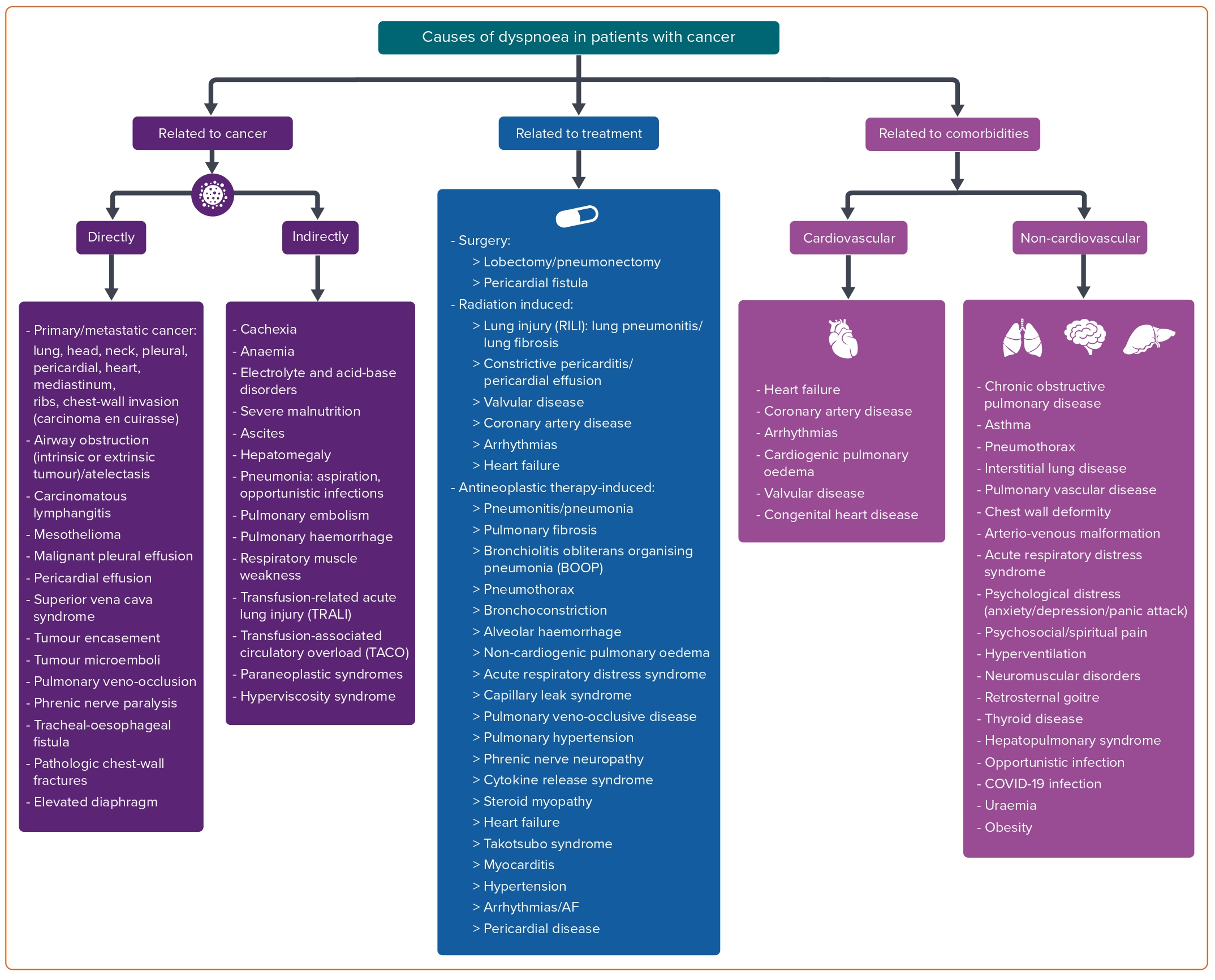

A proposed classification comprises causes related to cancer itself (directly or indirectly), causes related to anti-cancer treatment and a third category of causes related to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities independent of cancer (Figure 1).

Causes of dyspnoea related directly to cancer include primary and metastatic neoplasms of the head and neck and of the thorax (lungs, heart, pleura, mediastinum, ribs and chest wall), airway obstruction and atelectasis, pericardial and pleural effusion, superior vena cava syndrome, tumour encasement and/or microemboli, carcinomatous lymphangitis, phrenic nerve paralysis, tracheal-oesophageal fistula, pathological chest wall fractures, elevated diaphragm and pulmonary veno-occlusion.

Causes of dyspnoea indirectly related to cancer comprise pneumonia due to aspiration or opportunistic infections, pulmonary embolism and/or haemorrhage, respiratory muscle weakness, ascites, hepatomegaly, paraneoplastic syndrome, hyperviscosity syndrome, cachexia, anaemia, electrolyte and acid-base disorders, severe malnutrition, transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload.

Anti-cancer treatments (surgery, radiation therapy and antineoplastic drugs) may induce dyspnoea through cardiovascular toxicities or non-cardiovascular clinical syndromes. Certain types of surgeries (such as lobectomy and pneumonectomy) and surgical complications (such as pericardial fistula) may lead to dyspnoea. Radiation therapy can affect the lungs (radiation-induced lung injury) and/or the cardiovascular system (leading to coronary artery disease, valvular disease, heart failure, pericardial disease or arrhythmias). The development of dyspnoea is a common symptom of these issues.

Several categories of antineoplastic drugs, including classical chemotherapeutics, targeted therapies, immunotherapies and various other agents may induce dyspnoea as part of various clinical syndromes related or not related to cardiotoxicity. In these cases, dyspnoea is due to the insult of the respiratory system, resulting in pneumonitis, pneumonia, alveolar haemorrhage, acute respiratory distress syndrome, interstitial lung disease, acute bronchospasm, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, thromboembolic disease, pulmonary oedema, pleural disease/effusion and phrenic nerve paralysis.

The drug classes that have been associated with dyspnoea through these clinical syndromes are presented in Supplementary Material Table 1. The same table shows the cardiovascular toxicities of the same treatments which can lead to patients presenting with dyspnoea. These include heart failure, myocarditis, takotsubo syndrome, hypertension, pericardial diseases and arrhythmias, usually tachyarrhythmias.

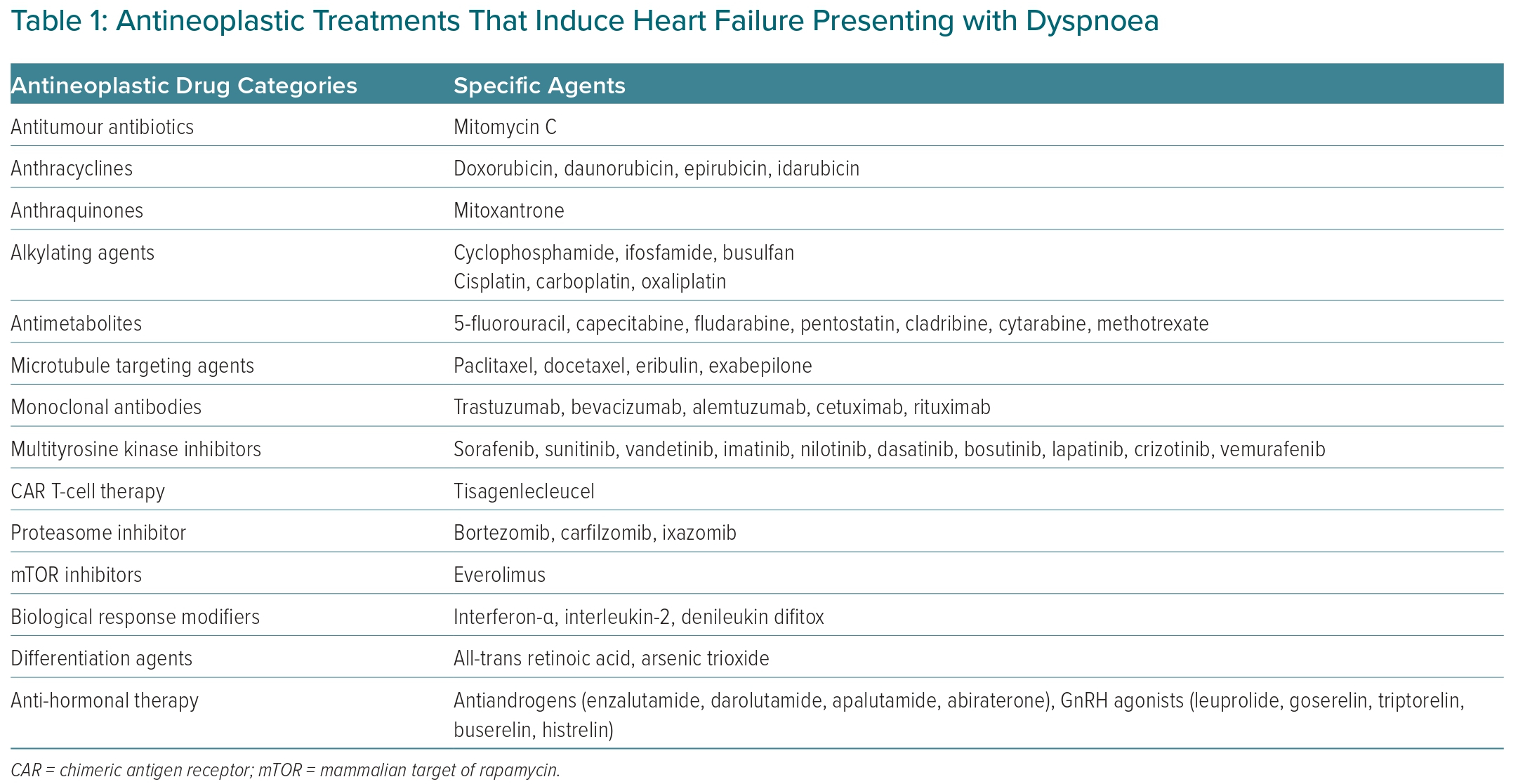

The most common cardiotoxic effect of antineoplastic treatment that presents with dyspnoea is heart failure. Most categories of anti-cancer drugs can cause myocardial dysfunction and heart failure (Table 1), with anthracyclines being the most well-studied.

On the other hand, the list of cancer drug categories that induce myocarditis is much shorter, with the most common category being immune checkpoint inhibitors (Supplementary Material Table 2). Oncological patients with myocardial ischaemia may also report dyspnoea as the cardinal symptom, with several antineoplastic drugs being responsible for it (Supplementary Material Table 3).

The incidence of takotsubo syndrome is higher in cancer patients than in the general population, and dyspnoea may be the only presenting symptom. At least seven drug categories and several combinations of them are related to takotsubo syndrome in cancer (Supplementary Material Table 4).14

Hypertension is more prevalent in cancer patients and survivors than in the general population.15 Of the cancer drugs associated with this (Supplementary Material Table 5), vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors are the most common example.

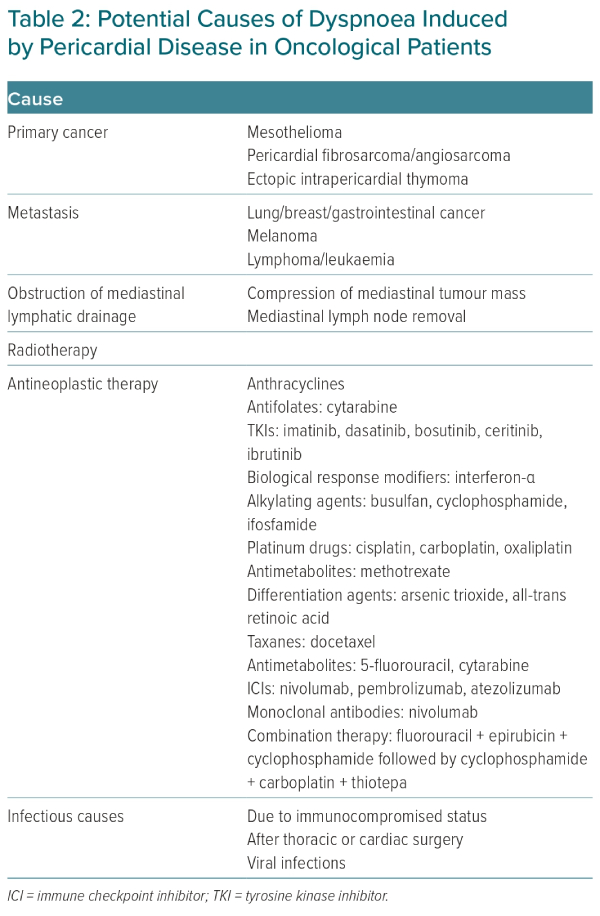

Pericardial diseases that can cause dyspnoea in cancer patients include myopericarditis, effusive or constrictive pericarditis and pericardial effusion with or without tamponade.16 Apart from radiotherapy, the anti-cancer drugs responsible for them are presented in Table 2.

Tachyarrhythmias can also cause shortness of breath in this patient population. AF is the most common arrhythmia in the general population and has a higher prevalence in cancer patients.17 Numerous cancer drugs have been associated with AF, which leads to a poorer prognosis in oncological patients (Supplementary Material Table 6).18

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Dyspnoea in Cancer

The physiological mechanisms that interact to control breathing are complex and incompletely understood. As a result, the pathophysiology of dyspnoea is multifactorial and encompasses a wide range of systems.

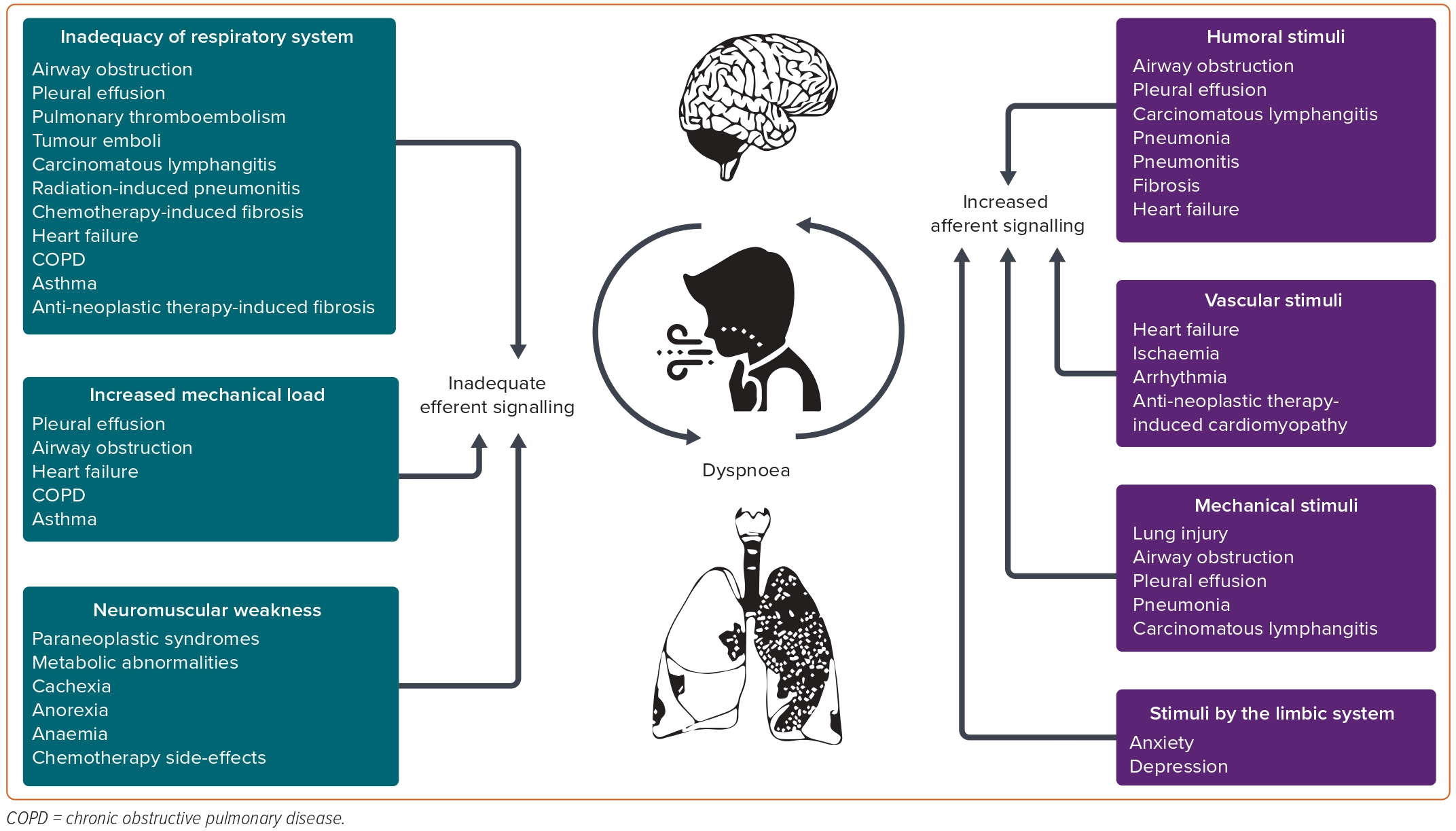

A common pathway in the pathogenesis of this symptom is the presence of a stimulus towards the respiratory centre (afferent signalling) which is not met by an adequate response by the latter (efferent signalling).19

Afferent signalling may be derived from: humoral stimuli, such as hypoxia, hypercapnia or acidosis detected through the carotid and aortic bodies and central chemoreceptors; vascular stimuli through atrial and ventricular receptors; mechanical stimuli by receptors in muscle spindles, in intercostal muscles and exercising limbs, as well as by vagal stretch receptors, J-receptors and C-fibres in the airways, alveolar walls and interstitium of the lungs; and stimuli by the limbic structures in the brain (Figure 2).

When increased or even normal afferent signalling is not met by a matching efferent one, dyspnoea occurs. Mechanisms may include alterations in elements of the respiratory system (such as the respiratory controller, the ventilatory pump or the gas exchanger); imposition of an increased mechanical load on the respiratory system (increased airway resistance, decreased lung or chest wall compliance); and neuromuscular weakness, even in the presence of normal load.

Specifically, in patients with cancer, there are several factors (anatomical and functional) that affect the aforementioned mechanisms responsible for dyspnoea.

Anatomical factors include: metastatic deposits in the lungs, which affect the respiratory centre by increased central motor output; vascular obstructions, such as pulmonary thromboembolism and tumour emboli, which reduce gas exchange efficiency; anatomic airway obstructions (tumours of the pharynx, the larynx or extrinsic compression due to progressive intrathoracic neoplasms) that increase airflow resistance and/or lung elastance and thoracic impedance; pleural effusion, which changes pulmonary elastance; and chemotherapy- and radiation-induced lung injury and lymphangitic carcinomatosis that lead to increased pulmonary elastance.

Functional factors in patients with a malignancy that induce dyspnoea either at rest or on exertion include respiratory muscle fatigue and weakness caused by paraneoplastic syndromes, paralysis of a hemidiaphragm, chemotherapy effects, anorexia, cachexia and metabolic abnormalities; skeletal muscle deconditioning induced by inactivity due to pain, weakness, anti-cancer therapies and their side-effects; lung parenchyma infections that increase metabolic demands, alter gas exchange and decrease pulmonary elastance; chemotherapy-induced heart failure that leads to pulmonary congestion; and increased metabolic demand induced by fever, anaemia or acidosis that increase ventilatory demands.

Predictors of Dyspnoea in Cancer

Predictive risk factors for dyspnoea development in terminally ill cancer inpatients are primary lung cancer, and poor ability to perform ordinary tasks as defined by a Karnofsky performance status score ≤40 and ascites.20 Furthermore, liver, lung and lymph node metastases, Patient-Reported Functional Status score of ≥3, oxygen levels of <90% by pulse oximetry and a history of respiratory conditions have been reported as predictive risk factors of the severity of dyspnoea in patients with advanced cancer patients.21

Another recent study by Sung et al. showed that the frequency and timing of dyspnoea, frequency of cough, EQ5D index, perceived health status over the previous month and employment status predicted dyspnoea severity, while dyspnoea distress can be predicted only by the Manchester cough score.22

Assessment of Dyspnoea in Oncological Patients

Dyspnoea is a symptom that is usually overlooked in oncological patients, with clinicians relying on observation at rest when the patient may look comfortable. On the other hand, even objective physiological measures commonly used are weakly correlated with the subjective experience of dyspnoea. Consequently, relatively normal values of vital signs and lung function tests do not preclude dyspnoea.

In addition, since dyspnoea may be triggered by physical and emotional exertion, patients choose to avoid activities that make them feel uncomfortable.

Consequently, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of breathlessness in patients with cancer suggest that all patients (both inpatients and outpatients) should be routinely screened for dyspnoea with an emphasis on the activities that patients have stopped or reduced.23

Because the experience of dyspnoea is subjective, the gold standard for dyspnoea assessment is based on patient self-report.1,23 According to the Food and Drug Administration, a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM; such as a questionnaire plus the information and documentation that support its use) is a report that comes directly from the patient about the status of their health condition without their response being interpreted by a clinician or anyone else. The outcome can be measured in absolute terms (severity of a symptom or sign or state of a disease) or as a change from a previous measure.24

Specifically, in oncological trials, the PROMS that contribute to patients’ health-related quality of life are of critical importance and can be used as important endpoints. More than 40 PROMS for dyspnoea have been identified (e.g. Visual Analogue Scale of Dyspnoea (VAS-D), Grade of Breathlessness Scale, Dyspnoea Numerical Scale, Edmonton Symptom Assessment scale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30), Cancer Dyspnoea Scale, Short-Form of Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (SF-CRQ) and Dyspnoea-12 Questionnaire (D-12)).25–28 Some of them are presented in Supplementary Material Table 7. They range from single-item to multi-item scales and can be unidimensional, such as the Modified Borg Scale and Breathlessness Intensity Scale, to multidimensional scales, such as the Reduced Cancer Dyspnoea Scale (r-CDS) and the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale, which capture several domains of dyspnoea.

Treatment of Dyspnoea in Cancer

The first step is the identification of any potentially reversible, treatable cause (e.g. pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, pneumonitis, tumour-related obstruction, heart failure, pericardial effusion, arrhythmia or anaemia). Therapeutic measures here are specific, directed by the relevant guidelines.

Arranging a treatment plan is more difficult when no underlying cause has been identified and the treatment of dyspnoea is symptomatic.

Symptomatic Treatment of Dyspnoea in Cancer

Most of the interventions suggested for the symptom-oriented treatment of dyspnoea in cancer are supported by evidence from chronic respiratory disease trials since there is a lack of studies on cancer.

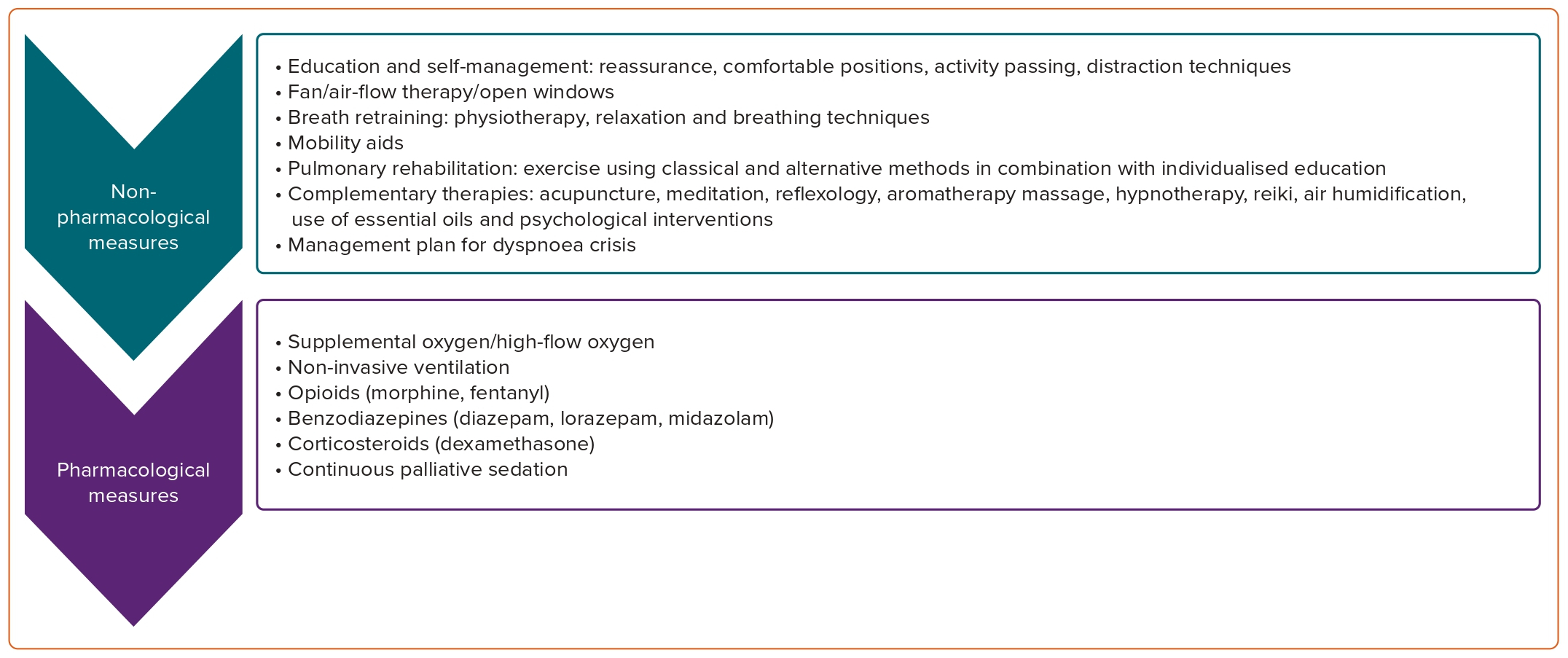

Symptomatic treatment includes non-pharmacological and pharmacological measures suggested by recent ESMO guidelines and presented in (Figure 3).23

Non-pharmacological measures include education of oncological patients and reassurance that dyspnoea is not life-threatening.

Certain positions can help recovery and reduce the distressing feeling of dyspnoea. Encouragement to establish a balance between resting and active periods is crucial to avoid extremes, which require prolonged periods of recovery.

Fan therapy, irrespective of patient’s oxygen saturation, has been suggested. Exercise improves physical capacity, lowers the relative level of ventilatory demand for a standard activity and reduces the perceived breathlessness and anxiety related to that. Programmes that combine aerobic and resistance training can be used to counteract deconditioning and to improve functional capacity.

Pharmacological measures can be considered when treatment of the underlying conditions and non-pharmacological measures do not relieve the patient’s symptoms.

Supplemental oxygen is indicated if SpO2 ≤90%. Non-invasive ventilation has been shown to improve dyspnoea, especially in hypercapnic patients and to reduce the use of rescue opioids. Systemic opioids seem to have a small-to-moderate effect on dyspnoea intensity in oncological patients.29 Benzodiazepines may reduce the anxiety related to dyspnoea and improve coping capacity.23 Despite limited clinical data, corticosteroids seem to have a positive effect on dyspnoea relief in patients with cancer and are particularly beneficial in dyspnoea due to lymphangitis carcinomatosis or tumour-related respiratory obstruction.23,30

Oncological patients with chronic dyspnoea should be referred to specialist multimodal breathlessness services if available and timely referral to palliative care services is crucial for patients and caregivers.

Continuous palliative sedation should be offered as a last resort to patients with terminal disease, very limited life expectancy (a few days) and severe refractory dyspnoea to all standard and palliative treatment options. It is intended to induce decreased awareness or unconsciousness to relieve the burden of intolerable distress.

This option may be discussed with the patient and the caregivers as part of the care plan before the patient is in a critical situation, when they will be able to understand the process, discuss the concerns and give consent.

Sedative medications include opioids, benzodiazepines (such as midazolam or lorazepam), first-generation antipsychotics (such as levomepromazine or chlorpromazine), phenobarbital or propofol.31

Conclusion

Dyspnoea in oncological patients is a multifactorial and potentially debilitating symptom, with greater prevalence and intensity in the terminal stages of cancer. The assessment of dyspnoea severity and impact on daily activities and QoL is challenging and the use of multidimensional scales is indicated. Symptomatic treatment of dyspnoea is suggested if no potentially reversible underlying cause is identified and timely referral to palliative care is beneficial.

Click here to view Supplementary Material.

Clinical Perspective

- Dyspnoea is a multifactorial, debilitating symptom in patients with cancer, which should be assessed thoroughly and treated efficiently to improve functional status and quality of life.