Although coronary functional abnormalities have fascinated cardiologists for more than 50 years, their existence has long been neglected.1 Before the advent of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), there were a high number of scientific publications regarding coronary functional abnormalities in general and coronary artery spasm in particular. However, after the introduction of PCI, the interest in this topic declined which was accompanied by a reduction in scientific publications on the subject. In recent years interest has grown again and the topic has been receiving more and more attention in the clinical arena. This is why the Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS) was founded and one of its main aims is to provide unified terminology and definitions for coronary vasomotion disorders.2,3 This may not only facilitate comparison of clinical test results from around the world but would also enhance clinical research and help to provide better care for patients. Knowledge about the definitions and epidemiology of coronary functional abnormalities is essential in this context.

Definitions of Coronary Functional Abnormalities

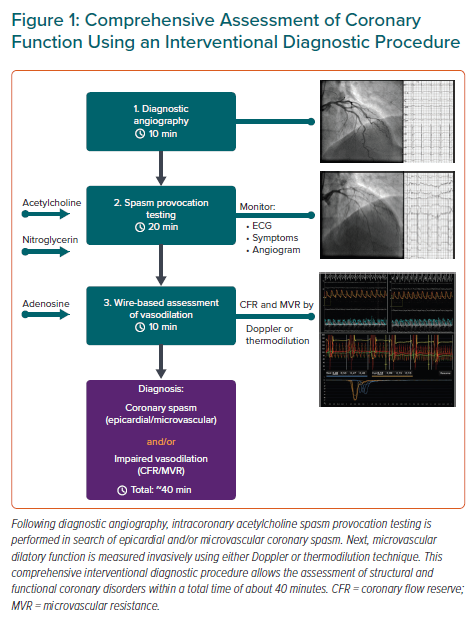

Although functional coronary abnormalities may occur in the presence or absence of epicardial stenoses they are particularly associated with patients with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries (ANOCA).4 Such patients are often labelled as having ‘non-cardiac chest pain’ and frequently have impaired quality of life.5 However, a significant proportion of these patients suffer from coronary functional abnormalities (for more details, see the below paragraph on epidemiology) and establishing a diagnosis of coronary functional abnormalities followed by stratified medical therapy can significantly improve quality of life.6 Patients with ANOCA may also include patients with angina in whom the haemodynamic relevance of moderate epicardial stenoses has been ruled out by using a pressure wire, for example. Several invasive investigations in patients with ANOCA are recommended by the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes.7 Intracoronary provocation testing in search of coronary spasm holds a Class IIa recommendation and wire-based investigations for measuring coronary flow reserve (CFR) and microvascular resistance in search of abnormalities of microvascular dilating function are equally recommended with a Class IIa recommendation. The comprehensive invasive assessment of coronary function is often referred to as interventional diagnostic procedure (IDP) (Figure 1). In the following section, we will focus on definitions of coronary functional abnormalities in patients with ANOCA.

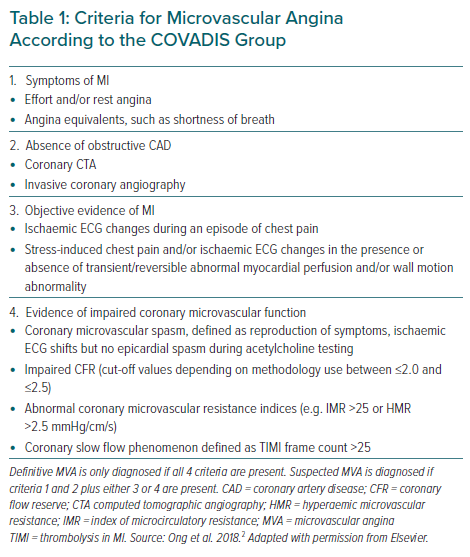

Functional abnormalities of the coronary circulation can be divided into those occurring in the epicardial arteries and those affecting the coronary microcirculation – a constellation also referred to as microvascular angina (Table 1). Usually, the latter is defined by a vessel diameter of <500 µm. It is also possible that vasomotion disorders affect the epicardial and the coronary microvessels in the same patient and a progression from microvascular to epicardial spasm over time has recently been suggested.8 However, data on the frequency of such a constellation are sparse.8–11

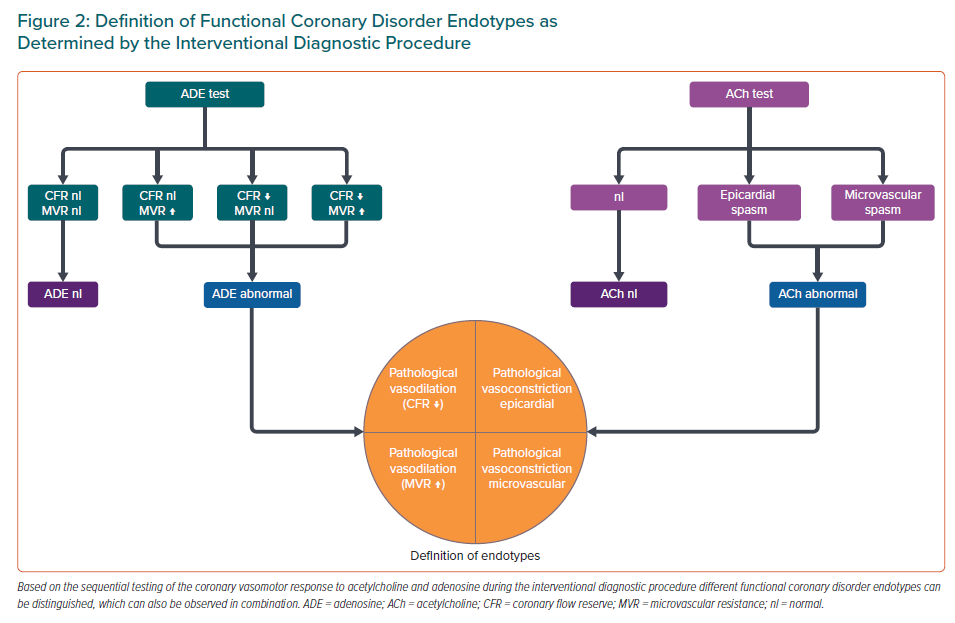

The two main mechanisms of functional coronary abnormalities are enhanced vasoconstriction and impaired vasodilatation.12 The former can be diagnosed during intracoronary provocation testing in search of coronary spasm using acetylcholine or ergonovine.4,13 The latter can be diagnosed by non-invasive techniques or invasively when CFR is measured with a dedicated wire (Doppler or thermodilution technique) using adenosine. The CFR is defined as the ratio between maximal coronary blood flow during adenosine-induced hyperaemia and resting flow at baseline. Usually, a value of ≤2.0–2.5 is considered to be abnormal, i.e. impaired CFR, with strong adverse prognostic data in patients with ANOCA.14,15 It should, however, be noted that an impaired CFR may be due to several constellations of resting and peak flow. On one hand CFR may be impaired because the microcirculation is unable to sufficiently dilate. In such instances resting flow may be normal but peak flow is impaired. On the other hand, a frequent observation is that resting flow is abnormally high, perhaps due to metabolic autoregulation in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors.16 This constellation may also lead to impaired CFR despite normal or near-normal adenosine flow. Whether these two different constellations when measuring CFR carry prognostic information is unknown but is currently under investigation.

Another important parameter that can be assessed simultaneously while measuring CFR is the index of microvascular resistance (IMR) when using the thermodilution technique or hyperaemic microvascular resistance (HMR) when using the Doppler technique. Both measurements reflect the coronary microvascular resistance during stimulation with adenosine and it is important to know that its calculation is independent of the resting flow. Impaired vasodilatation of the coronary microcirculation may be associated with structural alterations of the microvasculature, such as arteriolar remodelling and capillary rarefaction.17–19 Thus documentation of elevated hyperaemic resistance could be interpreted as indirect evidence of a structural phenomenon with or without an additional functional coronary abnormality. Theoretically, capillary rarefaction should also be associated with increased resistance at baseline. Nevertheless, microvascular structural alterations are frequently neglected and the term functional coronary abnormalities is often used as a distinction from structural epicardial (stenosing) coronary disease.20 In light of the aforementioned conditions, several disease endotypes can be defined (Figure 2). Here are the definitions of the most frequent endotypes based on the available evidence.

Epicardial coronary spasm:

- Reproduction of the patient’s symptoms during provocative testing.

- Ischaemic ECG shifts on simultaneous 12-lead ECG during provocative testing.

- Epicardial coronary constriction ≥90% diameter reduction during provocative testing.

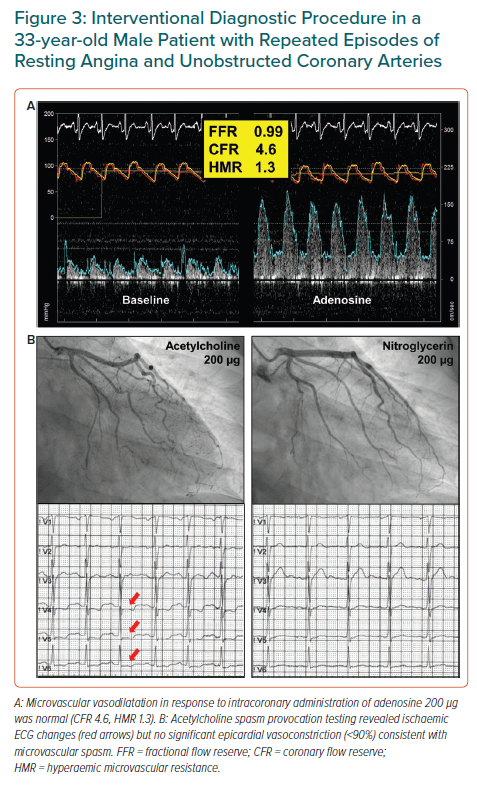

Microvascular coronary spasm (Figure 3):

- Reproduction of the patient’s symptoms during provocative testing.

- Ischaemic ECG shifts on simultaneous 12-lead ECG during provocative testing.

- Absence of epicardial coronary constriction ≥90% diameter reduction during provocative testing.

- In some centres, further evidence is generated by abnormal lactate concentrations from coronary sinus blood samples during provocative testing.

Impaired CFR:

- Depending on the Doppler or thermodilution technique, CFR is calculated based on average peak flow velocity (APV) or mean transit time (Tmn), respectively, as follows:

CFRDoppler = APVPeak /APVRest

and

CFRthermo = TmnRest /TmnPeak - Usually, a CFR ≤2.0–2.5 during flow measurements using a dedicated wire (Doppler or thermodilution technique) and adenosine infusions (IV or intracoronary) is considered abnormal.

Enhanced microvascular resistance:

- Microvascular resistance is calculated using distal intracoronary pressure and APV or Tmn as follows:

HMR = Pd/APVPeak

and

IMR = Pd* TmnPeak - Different cut-off values for HMR and IMR have been applied depending on the technique and the patient population.

- Frequently an IMR of >25 and an HMR of >2.4 are considered abnormal.

It is important to remember that in a given patient, several of the above-mentioned disease endotypes may be present.21,22 This not only leads to a high number of complex endotypes but also means that there may be patients with more than one coronary functional abnormality, e.g. coronary microvascular spasm and impaired CFR.

Consequently, understanding the pathophysiology in an individual patient, as well as creating well-characterised and homogeneous groups of endotypes for clinical trials is challenging.

Epidemiology of Coronary Functional Abnormalities

The true prevalence of patients with coronary functional abnormalities is difficult to determine as there are no reliable non-invasive tests that cover all the endotypes. Novel smart ECG devices may allow detection of ischaemic ECG shifts in patients with chest pain of unknown origin pointing towards a cardiac cause.23,24 It is currently unknown how often these symptoms are caused by stenosing coronary disease or a functional coronary abnormality. While common in patients with coronary artery spasm, the frequency of ischaemic ECG changes in patients with impaired CFR and/or increased microvascular resistance is unknown. Nevertheless, this represents an interesting area of investigation in contemporary precision medicine and upcoming studies are eagerly awaited. The number of patients with ANOCA will most likely further increase due to the fact that current guidelines recommend performing a coronary CT in patients with stable angina.25 However, despite the advantage of providing information on the presence and morphology of coronary plaque, this CT-based anatomical approach does not allow assessment of functional coronary abnormalities. Although few small studies have recently evaluated the feasibility of static or dynamic adenosine-stress CT perfusion examinations in patients with ANOCA, it is unclear whether these methods will enter clinical routine.26,27 Unfortunately, testing for functional abnormalities of vasoconstriction is not possible using CT.

Chronic Coronary Syndromes with Non-obstructed Coronary Arteries

It is well known that unobstructed coronary arteries are found in more than 50% of cases when looking at patients with chronic coronary syndromes undergoing elective invasive diagnostic coronary angiography for suspected stenosing coronary disease.28 Although this number may be reduced by better patient selection, the number of patients with ANOCA will remain high and they may even generate higher costs over time compared to patients with obstructive coronary disease.29 This underlines the high burden for our healthcare systems and highlights the need for appropriate diagnostic assessments in search of coronary functional abnormalities.

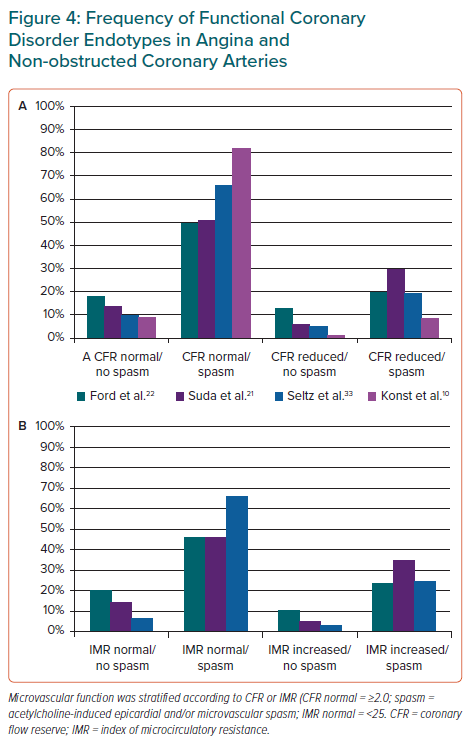

The frequency of coronary functional abnormalities in patients with ANOCA has been extensively investigated. Most older studies only looked at certain disease endotypes, such as coronary spasm only or impaired CFR only, and reported a prevalence of 50–60% in selected patients with ANOCA for each pathomechanism.30–32 Recent studies focused on the comprehensive assessment of coronary function resulting in a growing body of evidence regarding the frequency of enhanced coronary vasoconstriction, impaired microvascular vasodilatation (i.e. reduced CFR or increased microvascular resistance) or a combination thereof (Figure 4).10,21,22,33 Notably, these trials unanimously suggest that in patients with ANOCA enhanced vasoconstriction (coronary spasm) is much more frequent than impaired vasodilatation. This has important implications not only for future clinical trials but also for daily practice given that – in contrast to impaired CFR which can be assessed non-invasively using positron emission tomography or MRI – coronary vasoconstriction can only be reliably assessed invasively by spasm provocation testing.

Acute Coronary Syndromes with Non-obstructed Coronary Arteries

While the frequency of obstructive coronary artery disease is higher in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) compared to those with chronic coronary syndromes, up to 25% of patients presenting with ACS are found to have non-obstructed coronary arteries.34 This group comprises patients with MI with non-obstructed coronary arteries (MINOCA), as well as patients with unstable angina. Various pathomechanisms may be responsible for this emergent clinical scenario, including – but not limited to – pericarditis, myocarditis, takotsubo syndrome, plaque erosion, spontaneous coronary dissection, valvular heart disease, systemic diseases and functional coronary disorders.35 The prevalence of coronary artery spasm is high in this patient population.34,36,37 Although being safe in the acute setting, appropriate testing is rarely performed in clinical practice.34,37,38

Previous Successful Myocardial Revascularisation

Studies have shown that up to 50% of patients with successful PCI complain of ongoing or recurrent angina after the procedure.39,40 Such patients represent another important group of patients in whom investigations of coronary functional abnormalities should be performed. Studies have shown that coronary functional abnormalities can be found in ~60–70% of patients who have had previous successful myocardial revascularisation procedures and have ongoing/recurrent symptoms.41,42

Sex-related Differences

Several studies have shown that coronary functional abnormalities are more often found in women compared to men with some trials, such as the WISE study, focusing exclusively on women, however, systematic analyses have found only modest female preponderance.31,43,44 Moreover, prognosis in patients with ANOCA and reduced CFR was found to be equally impaired in men and women.45 Considering the frequent persistence of symptoms following coronary interventions for obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) one may speculate that many men with obstructive CAD have additional functional coronary abnormalities. Thus, the prevalence of functional abnormalities may be the same in both sexes, but it is under-recognised in men because testing is not performed if coronary stenoses are detected. Coronary functional abnormalities should therefore be considered in all patients with angina in daily clinical practice and future studies should provide more evidence regarding sex differences in this field.32

Conclusion

The high number of patients with ANOCA should prompt further assessments in search of functional coronary abnormalities as suggested by the current guidelines. Knowledge about the current definitions and frequencies of coronary functional abnormality endotypes is essential for appropriate classification and selection of the most effective pharmacological treatments.