Globally, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality in women. Approximately 2.8 million women have been diagnosed with CVD in the UK.1 For many years, the presence of gender-related differences in presentation, risk factors and outcomes have been recognised. Importantly, these discrepancies in presentation and outcomes between the sexes are often associated with inequalities in the detection, referral and management of CVD.

There is a lack of gender-specific evidence due to the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials and a long-held myth that CVD is limited to men. Women present with ischaemic heart disease about a decade later than men. This usually occurs in the postmenopausal period, during which time the protective effects of oestrogen are attenuated. Furthermore, population-based risk reduction in women has not resulted in improvements in the incidence of CVD compared to men. There was a significant decline in the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) in men between 1979 and 1994, and a comparative increase in the incidence in older women during the same period.2 Further evidence supporting this finding from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys demonstrated an increase in the prevalence of MIs in women in the 35–54 year age range, while a decline in prevalence was observed in age-matched men.3 It follows that early and accurate diagnosis of CVD is pivotal to reduce mortality rates in women.

Gender Differences in the Clinical Presentation of CVD

The evaluation of cardiovascular symptoms in women remains challenging due to the atypical nature of presentation. In addition, the use of ‘typical’ angina symptoms in the assessment of females may be imprecise due to the transposition of symptoms derived from male cohorts.4

The Framingham Heart Study initially described the pattern of presentation in women in the 1980s, and demonstrated that females generally develop angina as the initial presentation of ischaemic heart disease and are less likely to present with an acute MI compared with men.5,6 In acute coronary syndrome, women also present more commonly with unstable angina, rather than ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.7,8

In contrast, a study of 246 women and 276 men demonstrated no gender differences in the sensitivity of typical symptoms, defined as chest pain or discomfort, dyspnoea, diaphoresis and arm or shoulder pain, in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes.9 Women tend to present less frequently with exertional symptoms of chest pain prior to an acute MI.10 Differences in presentation tend to be more polarised among younger patients compared with older individuals. Supporting this finding, a study of >10,000 patients showed that older women (>65 years) presented with symptoms comparable to men and had a greater frequency of typical angina.11

Current data suggest that in women, symptoms of chest pain are less discriminatory in predicting obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) than in men.12 This finding has been well documented, and almost 40 years ago Diamond and Forrester suggested that when assessed with coronary angiography for typical or atypical symptoms relating to myocardial ischaemia, women demonstrated lower rates of obstructive CAD compared with men.13

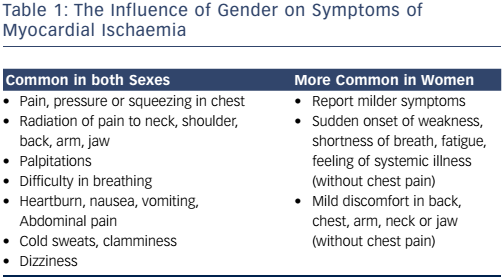

In established CVD, both men and women present with chest pain. Women report additional, potentially gender-related, non-specific symptoms, however, such as fatigue and sleep disturbance (see Table 1). The presentation may therefore confound the diagnosis, making dismissal of these symptoms as non-cardiac all the more perilous.14,15

Gender Similarities and Differences in Risk Factors for CVD

Despite men and women sharing classic cardiovascular risk factors, the relative importance of each risk factor may be gender specific. For example, the deleterious impact of smoking is greater in women than men, especially in those <50 years of age.16,17 Smoking also downregulates oestrogen-dependent vasodilatation via biochemical effects on the endothelial wall.18

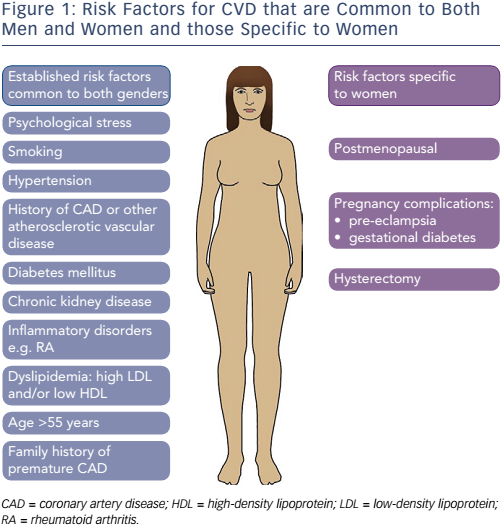

During assessment of CVD risk, typical risk factors must be considered including age >55 years, pre-existing CAD, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus, among others (see Figure 1). Risk factors that are specific to women include postmenopausal status, hysterectomy and complications during pregnancy. Women who go on to develop gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia more than double their risk of developing CVD later in life.19

Physical inactivity remains a significant risk factor for CVD. The Duke Activity Status Index is a risk stratification tool comprising a 12-item questionnaire measuring functional capacity. When compared to women who engaged in greater levels of physical activity, those performing <4.7 metabolic equivalents of effort in the form of activities of daily living were subject to a 3.7-fold increased risk of death or non-fatal MI.20

The Effects of Menopause on CVD Risk

Transition to postmenopausal status is associated with a worsening coronary heart disease (CHD) risk profile in women, conveying the same degree of cardiovascular risk as being male.21,22 The effects of the menopause include an increase in body weight, alteration in fat distribution, centripetal obesity and visceral fat deposition, with an associated increase in other CVD risk factors such as diabetes mellitus.23 In particular, diabetes is a potent risk factor in women. A meta-analysis of 37 studies and almost 450,000 patients revealed a 50 % greater relative risk of fatal CHD compared to men with the disease.24 This substantial gender difference in mortality is associated with a more adverse risk factor profile, smaller coronary vessel diameter and often suboptimal management of diabetes in women.

As oestrogen production wanes in ageing women, systolic blood pressure tends to increase and is modulated by the increase in plasma-renin activity.25–27 In women >75, isolated systolic hypertension is 14 % more prevalent than in men and causes significant morbidity due to left ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic heart failure and cerebrovascular disease.28

In younger women, the relative risk of hypercholesterolaemia is lower compared with men; the postmenopausal state, however, is associated with a more adverse lipid profile, with total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels increasing by 10 % and 14 %, respectively, without a significant change in high-density lipoprotein levels.21,29 Postmenopausal reassessment of lipids is therefore an important consideration in women with a borderline premenopausal profile. In women >65 years, mean LDL is higher than in men; however LDL reduction with statins reduces CHD mortality to a similar extent as in men.30

Microvascular Angina

This term refers to patients with symptoms of angina, displaying abnormalities on stress testing despite demonstrating normal coronary arteries on angiography. There is a well documented predilection for women to develop microvascular angina, and in a study of 886 patients presenting with chest pain and subsequently undergoing coronary angiography, women were five times as likely to have normal coronary arteries than men.31 The same risk factors leading to atherosclerosis may cause microvascular disease, however, with low oestrogen levels in women also implicated. The main aim of treatment is symptom control using calcium-channel blockers and oral nitrates.

Stress (Takotsubo) Cardiomyopathy

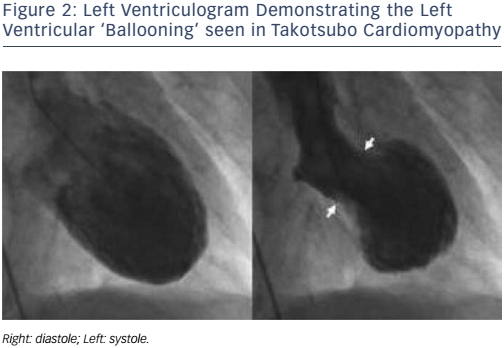

Stress cardiomyopathy is triggered by intense, unexpected emotional or physical stress and is characterised by temporary apical systolic dysfunction with ballooning of the left ventricle (see Figure 2). The syndrome predominantly affects postmenopausal women. This was demonstrated in a study of 1,750 patients from 26 centres, where almost 90 % of those affected were women with a mean age of 66.4 years.32 Presentation is similar to acute MI, with ST-segment elevation on the ECG and raised cardiac troponin levels. However, angiography does not reveal obstructive coronary disease and the observed regional wall motion abnormality is not limited to the territory supplied by a single coronary artery. The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood but catecholamine toxicity, microvascular dysfunction and coronary artery spasm have all been highlighted as possible pathogenic processes. There may be a genetic component in those predisposed to stress cardiomyopathy, with the identification of familial cases; however more convincing is the finding that 56 % of sufferers had a psychiatric or neurological disorder compared to 26 % of patients with acute coronary syndromes.32

Gender Differences in the Management of CVD

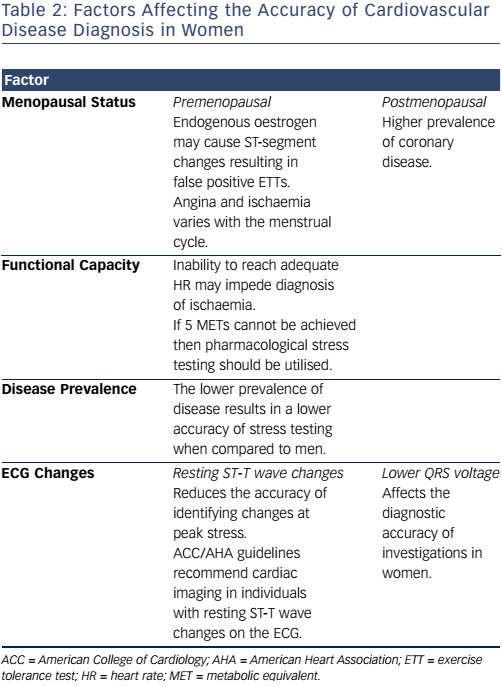

Underestimation of cardiovascular risk in women results in delayed or even missed diagnoses of CVD. The use of investigations to detect severe coronary stenosis is often futile, as women have a lower prevalence of obstructive CAD but have greater symptom burden and functional impairment (see Table 2). The management of stable angina in both sexes remains similar, and includes lifestyle modifications, anti-anginal medications and pharmacological secondary prevention, revascularisation and rehabilitation.33

The Role of Cardiac Investigations

The exercise ECG is of limited use in the evaluation of chest pain in women, owing to lower diagnostic accuracy for CAD compared to men (sensitivity and specificity ~60–70 % versus ~80 %, respectively).34,35 Hormonal variations may contribute to falsepositive rates in premenopausal women and hormone replacement therapy may cause false-negative results due to its vasodilatory properties.36 There are also gender-related difficulties in reaching an adequate level of exercise (>5 metabolic equivalents) to diagnose inducible ischaemia.20

Pharmacological stress testing is an accurate diagnostic technique and is preferred for diagnosing CAD in females with lower exercise capacity.37 Stress echocardiography using dobutamine has a sensitivity and specificity of 85 % and 75 %, respectively, for detecting CAD.10,20

Computed tomography coronary angiography has similar diagnostic accuracy in detecting ≥50 % and ≥70 % coronary stenosis in women and men, respectively.38 Of note, in women >55 years with intermediate risk for CHD, the lack of coronary calcium has a high negative predictive value (99 %).39

Single-photon emission computed tomography is a highly accurate nuclear imaging technique used to evaluate stress-induced myocardial perfusion defects, although image quality can be affected by breast tissue and obesity, which may result in false-positive outcomes in women.

Gender-dependent Outcomes

Recent data suggest that both men and women presenting with stable angina are subject to increased mortality when compared with the general population.40 In fact stable angina is no longer viewed as a benign condition in women, with evidence to support this from the Euro Heart Survey of Stable Angina demonstrating that during the 1-year follow-up period, women had double the risk of death or non fatal acute MI compared with men.41

The subgroups of CVD also have varying outcomes. Women presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction have worse outcomes compared to men, but in those presenting with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction no sex-dependent differences in outcome were demonstrated.42

Improvements in the Identification and Management of Women with CVD

Despite similar recommendations for men and women, it has been well documented that diagnostic procedures and secondary prevention are not delivered to women with the same intensity. Past clinical trials have predominantly recruited men, making it difficult to determine any gender-specific advantages. Medical management affects men and women in different ways and should therefore be tailored to gender accordingly, for example beta-blockers have been found to provide greater survival benefit in women with acute MI.43

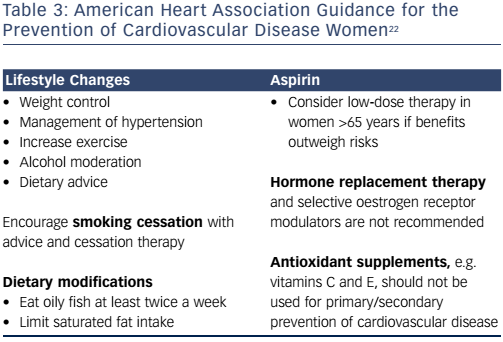

The 2011 American Heart Association guideline for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women highlights the importance of lifestyle modification, smoking cessation and diet in order to reduce the morbidity and mortality related to CVD (see Table 3).22 These guidelines should form the basis of national strategies aiming to reduce CVD in women.

Conclusion

CVD in women continues to be a major public health issue due to the difficulties facing physicians in identifying associated symptoms. There are significant gender-specific differences in presentation, response to treatment and outcomes. In 2007, the annual mortality of women secondary to CAD was 4.7 times that of breast cancer, the most common type of cancer in the UK.44

The misconception that women are protected against CVD makes its management all the more challenging. Variation between genders may be related to differences in pathophysiology or merely differences in the detection of CVD. An understanding of these variables is essential in developing gender-specific CVD prevention, and in the identification and management of CVD in women in order to have a beneficial effect on morbidity and mortality.