The management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) varies across the Asia-Pacific region.1 In particular, there is significant heterogeneity regarding the use of reperfusion techniques and pharmacological management.1 For example, thrombolysis is commonly used for reperfusion in China, India and parts of South-East Asia, whereas percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are more common in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand.1

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with a P2Y12 inhibitor and aspirin is generally recommended for at least 1 year following an ACS, or longer for patients with a high ischaemic/low bleeding risk.2,3 However, there is considerable variation in DAPT duration across Asia and a one-size-fits-all approach based on Western guidelines may not be appropriate for Asian populations.4 For example, genetic polymorphisms (i.e. polymorphisms affecting CYP2C19 function) associated with a slower rate of bioactivation of clopidogrel have a substantially higher prevalence in Asian people (29–60%) than Caucasian people (15%).5 Furthermore, the ‘East Asian paradox’ results in a different benefit–risk profile, where the risk of ischaemic events is lower, and bleeding higher, than Western populations, despite higher average on-treatment platelet reactivity.6,7 Nevertheless, data generated from Asian patients are limited and rarely incorporated into major international guidelines.

Newer oral therapies have been developed offering faster onset, more potent platelet inhibition and lower response variability than clopidogrel. Ticagrelor, a cyclo-pentyl-triazolo-pyrimidine, has a reversible, direct-acting mechanism of action that is not impacted by CYP2C19 polymorphisms and prasugrel, a thienopyridine prodrug, is less susceptible to CYP2C19 polymorphisms than clopidogrel.8–11 We aim to summarise key evidence and provide recommendations on the use of P2Y12 inhibitors in Asian patients.

Methods

The Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) convened a panel of 22 experts from 13 countries in Asia-Pacific with clinical and research expertise in the use of P2Y12 inhibitors, to develop consensus statements on the use of these class of drugs in ACS patients in the Asia-Pacific region. The experts were members of the APSC who were nominated by national societies and endorsed by the APSC consensus board. After a comprehensive literature search, with particular focus on Asian-centric studies, selected applicable articles were reviewed and appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system, as follows:

- High (authors have high confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect).

- Moderate (authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect).

- Low (true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect).

- Very low (true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).12

The available evidence was then discussed during two consensus meetings. Consensus statements were developed during these meetings, which were then put to an online vote. Each statement was voted on by each panel member using a three-point scale (agree, neutral or disagree). Consensus was reached when 80% of votes for a statement were agree or neutral. In the case of non-consensus, the statements were further discussed using email, then revised accordingly until the criteria for consensus was reached.

Results and Discussion

The efficacy and safety of ticagrelor was demonstrated in the Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO), which enrolled more than 18,500 patients with an ACS.13 The risk of cardiovascular (CV) death, MI or stroke with ticagrelor decreased by 16% compared with clopidogrel after 12 months, with benefit being observed within 30 days and accruing throughout the study period. Notably, ticagrelor reduced the risk of both CV death and recurrent non-fatal MI versus clopidogrel.

The PEGASUS-TIMI 54 study subsequently demonstrated a benefit when extending ticagrelor-based DAPT for up to 3 years.14

No difference in PLATO- or TIMI-defined major bleeding was observed between ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the PLATO study, but non-CABG-related and TIMI-defined major bleeding was significantly increased in PLATO and PEGASUS-TIMI 54, respectively.13,14 Ticagrelor was also associated with an increased risk of dyspnoea.13

No interaction between Asian/non-Asian ethnicity and efficacy was observed in PLATO.15 However, the overall event rate was higher in Asian patients, despite a similar bleeding risk.15 Southeast Asian patients also appeared to experience higher rates of ischaemic events and bleeding than East Asian patients.15

Two randomised but underpowered studies, PHILO and TICA KOREA, compared ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients.16,17 The risk of bleeding and ischaemic events was increased among East Asian patients with ACS from Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea in PHILO.16 Likewise, in TICA KOREA, the incidence of clinically significant bleeding was significantly higher with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among Koreans hospitalised for ACS with planned invasive management, while the incidence of CV death, MI, or stroke was also numerically higher in the ticagrelor arm.17

TRITON-TIMI 38 compared prasugrel with clopidogrel in patients with an ACS scheduled to undergo PCI; prasugrel reduced the risk of CV death, MI or stroke by 19% compared with clopidogrel, but the incidence of non-CABG-related TIMI major and life-threatening bleeding were significantly increased.18 As a result, a reduced 5 mg dose is indicated for patients aged ≥75 years or with body weight <60 kg, and prasugrel is contraindicated for those with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attacks.8

The PRASFIT-ACS study on Japanese patients with ACS undergoing PCI is the only randomised trial comparing the outcomes with prasugrel and clopidogrel in an exclusively Asian population.19 Notably, patients were administered markedly lower doses of prasugrel (20 mg loading/3.75 mg daily maintenance dosing), yet the incidence of CV death, MI or stroke was reduced by 23% at 24 weeks without significantly increasing non-CABG-related major bleeding. While the reduced risk of ischaemic events was not statistically significantly different, the result was comparable with the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, although follow-up was shorter.18,19

Only one randomised head-to-head comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor has been performed – the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT) 5 trial.20 In this open-label study the risk of CV death, MI, or stroke was 36% higher with ticagrelor than prasugrel at 1 year (9.3% versus 6.9%; p=0.006), while rates of major bleeding were similar.20 However, this result must be interpreted with caution because of the open-label design, high rate of drug discontinuation, an unexpectedly low rate of MI in the prasugrel arm and allowance for telephone follow-up of participants.20 No head-to-head studies comparing ticagrelor and prasugrel have been performed in Asian patients.

Overall, DAPT incorporating ticagrelor or prasugrel, instead of clopidogrel, reduces the risk of ischaemic events, but may increase the risk of bleeding.13,18 However, studies of ticagrelor and prasugrel have largely been performed in Western populations that may have a differing risk profile for both ischaemic and bleeding events versus Asian patients. Therefore, targeted guidance for physicians prescribing ticagrelor or prasugrel to Asian patients with an ACS are necessary.

ST-elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

Statement 1. A 12-month duration of therapy for ticagrelor (180 mg loading and 90 mg twice-daily maintenance dose) and prasugrel (60 mg loading and 10 mg daily) are effective and safe in the prevention of adverse cardiovascular events among patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and are recommended in patients who are undergoing primary PCI.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Statement 2. If aspirin and clopidogrel are introduced early in thrombolysis, a switch to ticagrelor should be considered the next day or after 8 hours.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 90.9% agree, 9.1% neutral, 0% disagree.

Both ticagrelor and prasugrel significantly reduce the risk of CV death, MI or stroke in patients with an ST-elevation ACS (STE-ACS) versus clopidogrel.21,22 However, ticagrelor and prasugrel have not been extensively studied in Asian patients with STE-ACS, so the use of clopidogrel should not be disregarded.

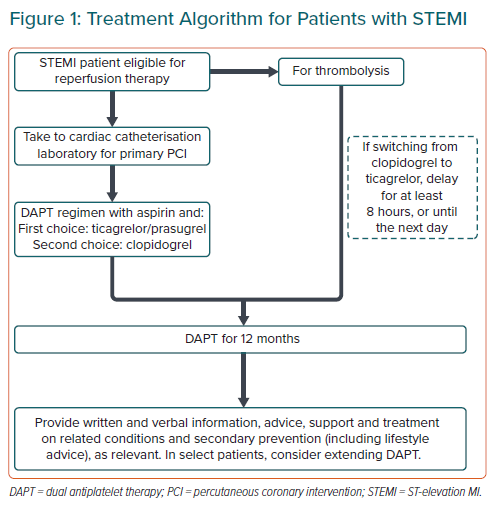

Antiplatelet therapy should be initiated upon diagnosis of STE-ACS, ideally before or while a patient is being transported to the hospital for primary PCI, in the absence of contraindications (e.g. severe bleeding; Figure 1).2,3 Prehospital administration of ticagrelor (i.e. in transit) to patients presenting with an STE-ACS is possible, but does not offer significant benefits beyond a reduced risk of stent thrombosis.23 Aspirin (300 mg or 325 mg loading dose and 75 mg or 81–100 mg maintenance dose) should be initiated for all STE-ACS patients prior to or at hospital presentation.2,3

For patients initially managed using thrombolysis, US and European guidelines recommend administering clopidogrel immediately, because ticagrelor was administered >24 hours after a STE-ACS in the PLATO study.2,24 The European guidelines note switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel or ticagrelor may be considered after 48 hours for patients who receive fibrinolysis and subsequently undergo PCI.24

No significant differences in the rate of TIMI major bleeding after 30 days in patients have been observed in STEMI patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel after undergoing fibrinolysis in an approximately 8-hour/next-day timeframe.25 Likewise, rates of major bleeding were similar after 12 months, indicating that early switching from clopidogrel to ticagrelor after fibrinolysis is feasible.26 The use of prasugrel after fibrinolysis for STEMI has not been well studied, so no recommendation is made.

Non-ST-elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

Statement 3. Ticagrelor (180 mg loading and 90 mg twice daily maintenance dose) is recommended in patients with non-STelevation ACS (NSTE-ACS). In patients receiving an early invasive strategy (<12 hours), pre-treatment may not be mandated.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0.0% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Statement 4. Prasugrel (60 mg loading and 10 mg daily) is recommended only in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention. In countries where a reduced loading or maintenance dose is approved, a reduced dose may be considered. Pre-treatment is not recommended.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Statement 5. Unless bleeding risk is high, a minimum of 6 months of DAPT is recommended to reduce ischaemic risk in NSTE-ACS.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 86.4% agree, 4.5% neutral, 9.1% disagree.

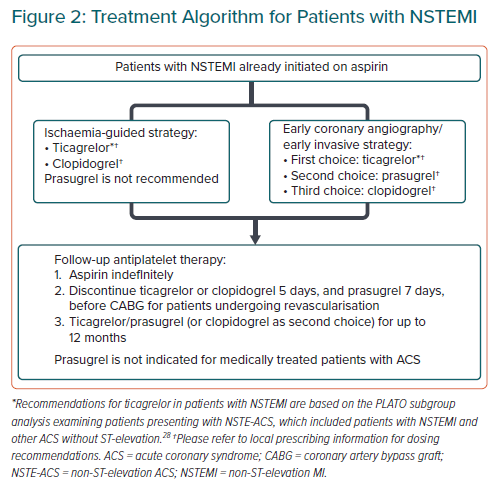

This consensus statement recommends the use of P2Y12 inhibitors as part of DAPT as a cornerstone intervention for NSTE-ACS (Figure 2), in a similar manner to Western guidelines.27

The efficacy and safety profile of ticagrelor in patients with NSTE-ACS is consistent with the overall PLATO study population.28 While a study in Chinese patients with NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI suggested that doubling the ticagrelor loading dose may achieve faster onset of platelet inhibition without an increase in adverse events, this is unlikely to be associated with a clinically meaningful benefit and is inconsistent with the approved ticagrelor label.9,10,29

No benefit has been observed versus placebo when initiating P2Y12 antiplatelet therapy when invasive procedures for ACS are planned within 12 hours of presentation, so routine pre-treatment prior to early invasive intervention is not mandated.30

The efficacy and safety of prasugrel was only investigated in patients who underwent PCI in TRITON-TIMI 38, and the approved indication has been limited accordingly.8,11,18 Reduced prasugrel dosing (20 mg loading/3.75 mg daily maintenance dosing) has demonstrated improved efficacy compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patients with ACS without significantly increasing non-CABG-related major bleeding, supporting lower indicated dosing in some Asian countries.19

Prasugrel pre-treatment prior to invasive procedures is not recommended because of the increased risk of bleeding without reducing the risk of ischaemic events.31

A net clinical benefit is expected for all patient groups with at least 6 months of DAPT after an ACS.32 However, for patients with a high risk of bleeding, the reduced risk of ischaemic events needs to be weighed against the risk of bleeding after 6 months.32 Furthermore, as pointed out by some panellists, the DAPT study evaluated a treatment duration of at least 12 months.

Bleeding Risk

Statement 6. There is no specific bleeding risk calculator recommended for use in Asian populations.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 95.5% agree, 4.5% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Statement 7. Ticagrelor or prasugrel in combination with aspirin should be considered as first-line for NSTE-ACS patients at high risk of ischaemia, unless patient has prior history of bleeding or is above 85 years old. Adjust the duration of therapy based on bleeding risk.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 72.8% agree, 0.0% neutral, 13.6% disagree.

Statement 8. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be considered for use in patients with high risk of bleeding. However, other causes of bleeding or anaemia should be investigated.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 100.0% agree, 0.0% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Statement 9. A radial access should be considered as default strategy for patients undergoing catheterisation.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 95.5% agree, 4.5% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Statement 10. Among patients on DAPT who are scheduled to undergo non-cardiac surgery, consider the risk associated with stopping DAPT or continuing aspirin alone versus delaying surgery until completion of 6 months of DAPT post-MI. A joint discussion between cardiologist and proceduralist regarding the risk of bleeding versus an ischaemic event following cessation of DAPT should be considered. Stop ticagrelor and clopidogrel 5 days, and prasugrel 7 days, prior to surgery.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 95.5% agree, 4.5% neutral, 0.0% disagree

A recommendation for a specific bleeding risk score was not recommended in Asia because there is no validated bleeding risk calculator for Asian patients. Post-ACS bleeding risk tends to be overestimated compared with ischaemic risk in Asian patients.33 Therefore, an individualised assessment of the benefit-risk ratio of DAPT should be performed on the basis of a patient’s medical history, physical examination, and laboratory parameters.

Both ticagrelor and prasugrel have demonstrated improved efficacy versus clopidogrel in patients with ACS undergoing revascularisation, although some panellists have highlighted that the data for prasugrel is only for PCI.18,34,35 No difference in the risk of major bleeding was observed between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in the Asian subgroup analysis of the PLATO study or in several real-world comparisons in Asian populations.15,36–38 However, other studies have suggested there is an increased risk of major bleeding with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in East Asian patients.16,17,39–43 The risk of bleeding with prasugrel has also been reported to be higher than for clopidogrel in Korean patients.44 The risk of any bleeding has been reported as being comparable between ticagrelor and prasugrel in East Asian patients.43 Therefore, duration of therapy should be based on a perceived on-going net clinical benefit.

No increase in the risk of bleeding or ischaemic events has been observed in patients administered ticagrelor or prasugrel versus clopidogrel alongside a PPI.45–47 However, PPI administration is associated with lower clopidogrel active metabolite levels and ex vivo-measured platelet inhibition.48

Bleeding complications may also be reduced with the use of a transradial access during PCI. A 2020 meta-analysis that included 18 randomised controlled trials (n=21,669) found that among patients with ACS who have undergone PCI, transradial access decreased the risk of major bleeding by 38% (p<0.001) compared to a transfemoral route.49 Radial access was also associated with a 25% lower risk of all-cause mortality (p=0.002). Both results were consistent across subgroups except in those that used bivalirudin as an anticoagulant, wherein no benefit was seen for major bleeding or mortality.

DAPT should not be stopped within 4 weeks of stenting unless it is for critical surgery. The ischaemic versus bleeding risk in patients treated with DAPT undergoing surgery must be weighed during pre-surgery discussions between the cardiologist and the proceduralist.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved label states that ticagrelor should be stopped for up to 5 days prior to elective surgery.9, 10

While the European Society of Cardiology 2017 guidelines recommend stopping treatment up to 3 days prior to surgery based on the results of the ONSET/OFFSET study, the panel does not support this recommendation because it is based on a single study.3,50 Clopidogrel and prasugrel treatment should be stopped 5 and 7 days before surgery, respectively.3

Switching Antiplatelet Therapy

Statement 11. Clinicians must evaluate reasons for de-escalation and weigh these against the risk of a possible ischaemic event. If de-escalation is necessary, this should be delayed for as long as possible (at least 1 month, but preferably >3 months after the ACS event) as risk of ischaemic events in revascularised patients decreases over time.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 86.4% agree, 13.7% neutral, 4.5% disagree.

Statement 12. Regardless of time frame, reloading is required when switching from ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel unless there is on-going bleeding.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 81.9% agree, 4.5% neutral, 13.6% disagree.

DAPT should be continued for a minimum of 12 months, unless contraindicated or not tolerated.2,3 De-escalation (change from ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel) may be required due to major bleeding, ambiguity surrounding dose requirements for elderly patients/patients with low body weight using prasugrel, or cost.51–53

De-escalation of ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel may reduce the risk of bleeding without compromising efficacy.54 However, observational data from Asian patients have suggested that de-escalating DAPT in the absence of platelet-function-testing-guided clopidogrel dosing may increase the risk of ischaemic events without reducing bleeding risk.38,51,53,55

If de-escalation to clopidogrel is necessary, de-escalation should be delayed as long as possible, preferably until >3 months after an ACS, and avoided <1 month after the event,56 because of the time-dependent decrease in the risk of ischaemic events following an ACS.

Data from patients who de-escalate DAPT is limited and a consensus on a de-escalation strategy has not been reached in the literature.

To guide practice despite the lack of strong evidence, the panel consensus is to consider a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel when de-escalating from ticagrelor to clopidogrel, irrespective of time from ACS. However, directly de-escalating to a 75 mg daily maintenance dose of clopidogrel is reasonable when de-escalation is due to bleeding.57

Long-term Versus Short-term Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

Statement 13. The standard duration of DAPT is 12 months after an ACS. Extension of DAPT beyond 1 year may be considered for high ischaemic-risk patients, such as those with high-risk stent anatomy, complex coronary anatomy or additional risk factors (e.g. diabetes). Clinicians must evaluate both ischaemic and bleeding risk.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 85.5% agree, 0.0% neutral, 4.5% disagree

Continuing DAPT with clopidogrel beyond 12 months has been shown to decrease the risk of ischaemic events, including CV death, among high-risk patients with a history of MI versus aspirin alone, but is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding.58 Similar outcomes when continuing DAPT with ticagrelor (60 or 90 mg) beyond 12 months were reported in the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, although there was no significant increase in the rate of fatal bleeding or intracranial haemorrhage.14 The FDA and EMA licensed the use of ticagrelor 60 mg from 12–36 months because of its comparable efficacy but lower risk of bleeding versus a 90-mg dose.9,10 DAPT using ticagrelor 60 mg beyond 12 months has also demonstrated a benefit compared with placebo in patients with concomitant multivessel disease or diabetes.59,60

Genotyping, CYP2C19 Polymorphisms and Platelet Function Testing

Statement 14. Due to the lack of positive prospective trials in Asian patients, the routine use of point-of-care platelet function testing to guide decisions in antiplatelet therapy is not recommended.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0.0% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Patients with a CYP2C19 poor metaboliser phenotype may not achieve adequate platelet inhibition with the CYP219-dependent prodrug clopidogrel.5 In contrast, ticagrelor and prasugrel are not dependent on CYP2C19 bioactivation,5 but differences in bioactivation alone do not fully account for the reduced risk of ischaemic events with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel.61

CYP2C19 polymorphism-guided antiplatelet prescribing may improve clinical outcomes for patients with ACS and offers a cost-effective approach to treatment.62–64 Point-of-care platelet function testing may also act as a surrogate marker for CYP2C19 polymorphisms for patients administered clopidogrel.65 Nonetheless, despite the high prevalence of CYP2C19 polymorphisms in the Asia-Pacific region, routine use of genotype-guided DAPT is not recommended because of the lack of prospective randomised trials performed in the Asia-Pacific region demonstrating a clinical benefit, though further research is warranted.5,65,66

Special Populations

Statement 15. Ticagrelor has been shown to be effective and safe among specific populations (diabetes, elderly and chronic kidney disease [CKD]) with ACS.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 89.9% agree, 9.1% neutral, 0.0% disagree.

Caution and clinical judgment must be exercised when using DAPT in patients with comorbidities associated with an increased risk of ischaemic events and/or bleeding, such as diabetes or CKD, and in elderly patients (age >75 years).67–69 No dose adjustment is required for ticagrelor.9,10 A reduced 5 mg daily dose of prasugrel is required for patients weighing <60 kg and prasugrel is not recommended for patients aged ≥75 years.8,67–69

Future Directions

Spontaneous major bleeding and bleeding associated with urgent invasive procedures remain concerns for patients administered DAPT following an ACS. In particular, the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor cannot be reversed with platelet transfusion.70 A candidate reversal agent is PB2452 (PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals), a monoclonal antibody fragment that binds ticagrelor, is under investigation and has demonstrated immediate and sustained reversal of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor in a phase 1 study.70

Efforts to prospectively investigate the efficacy and safety of CYP2C19 polymorphism-guided antiplatelet prescribing in Asia, and subsequent cost-effectiveness analyses, would be welcomed given the economic considerations that drive antiplatelet prescribing in the region.

Limitations

The breadth of literature on the role of ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel in ACS is diverse and these consensus recommendations are not exhaustive and are based on the best available evidence at the time of publication. The consensus statements are not intended to replace clinical judgement. Furthermore, the use of P2Y12 inhibitors in patients receiving oral anticoagulants due to concomitant AF was not discussed, and is discussed in another consensus document.

Conclusion

When managing Asian patients who have had an ACS with DAPT, there are different considerations compared with those for Western populations. While data from Asian populations comparing outcomes with ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel are limited, there is evidence to suggest that ticagrelor or prasugrel should be preferred over clopidogrel for most patients with ACS, particularly those who have undergone PCI. The decision on duration of DAPT – including the need to de-escalate, stop or continue therapy beyond 12 months – should be individualised, considering both the ischaemic and bleeding risk for each patient.