Mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a key clinical quality metric. Randomised clinical trials and registry studies have reported either comparable or worse survival for females compared to males following PCI.1–5 This sex-specific excess risk is likely to be multifactorial. Females undergoing PCI are typically older, with higher cardiovascular risk factors, and have a greater burden of comorbidities compared to males. Females also have less extensive epicardial coronary artery disease and present with more atypical symptoms.6–11 However, even after adjustments for these clinical differences, study findings remain inconsistent.12,13

In most population-based studies, the natural survival of females has been higher than males.14 Since natural survival is heavily age-dependent, it is crucial to evaluate sex-specific survival within specific age groups. Observed survival rates following PCI are not constant and often experience a significant decline in the immediate post-PCI period. Integrating these considerations into survival analyses would enhance our understanding of overall prognosis and unveil sex-specific disparities in future mortality risk.

Relative survival compares the observed crude survival in the cohort of interest with the age- and sex-matched expected survival in the general population, and provides an unbiased assessment of real-world mortality while mitigating the impact of competing risks or coexisting risk factors.15 Conditional survival, or landmark analysis, estimates survival probability from a certain time point onward, assuming the patient has already survived up to that time point, and enables straightforward dynamic survival modeling.16 Combining these approaches and plotting against can illuminate sex-specific survival differences following PCI.

We compared 5-year observed and relative survival between males and females PCI patients using nationwide healthcare data.

Methods

Study Design and Definitions

This study retrospectively analysed anonymised medical claims from the National Healthcare Insurance Service, a unique compulsory healthcare insurance system in South Korea.

The index PCI date was the date of the first PCI performed during the selection period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2011. Clinical risk factors were identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes and administrative claims in the look-back period from 1 January 2009 to 1 day before the index PCI date. Death records during the follow-up period, from the index PCI date to the end of the selection period, were retrieved from Statistics Korea. Diabetes was defined by corresponding ICD-10 codes and at least two HbA1c tests within 1 year. Stroke was identified through relevant ICD-10 codes and hospital admission with brain imaging within 7 days. Shock was defined by claims associated with cardiogenic shock, such as resuscitation, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, and use of haemodynamic support devices, including intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Other clinical conditions were defined using the operational definitions using diagnosis code listed in the Supplementary Material. Follow-up was considered complete upon confirmed death or any administrative claims issuance during the follow-up period. No patient was lost to follow-up regarding death, with a 5-year follow-up available for 94.8% of patients. Primary outcome was 5-year all-cause death.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using χ2 test or Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative incidence of death were compared using a Cox proportional hazard model, with HR and 95% CI. Relative survival was calculated by comparing the observed survival of the patients to the expected survival in the general population, using life tables provided by the Korean Statistical Information Service and the Ederer II method. Comparisons of relative survivals were performed using a Cox model with transformed time.17

As the mortality is age-dependent, the RR of observed survival across ages was evaluated using a restricted penalised spline model, with the survival of 60-year-old males serving as the reference. Additionally, observed and relative survivals conditional on surviving 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years were evaluated. It enabled separate examination of sex-specific differences in both the early post-PCI period, wherein females typically have a higher risk of periprocedural complications than males, and in later periods.18

To minimise bias caused by the clinical characteristic differences between males and females, an age group-stratified clinical characteristics-matched cohort was created. Propensity scores were calculated based on parameters including age, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney disease, neoplasm, prior medical history of stroke, MI, revascularisation, resuscitation, shock, stent materials (bare metal stents, first- or second-generation drug-eluting stents) and numbers, as well as diagnosis, including angina, non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI), or ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 4.3. Statistical significance was defined as two-tailed p<0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

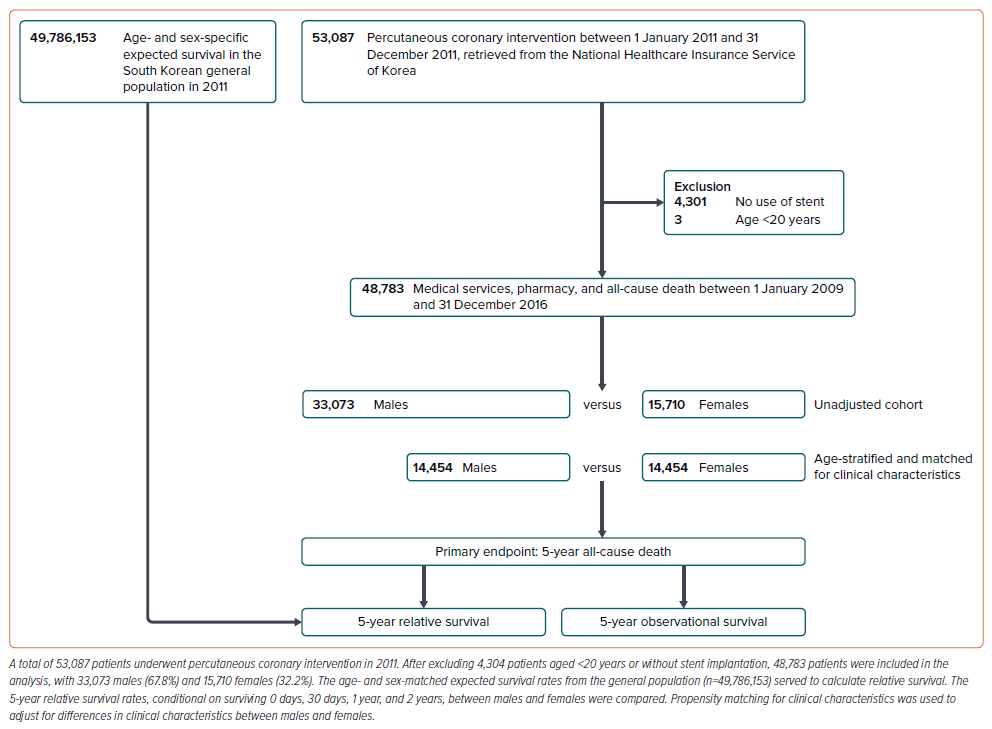

A total of 53,087 patients underwent PCI during the selection period. After exclusion of 4,304 patients aged <20 years or without stent implantation, 48,783 patients comprising 33,073 males (67.8%) and 15,710 females (32.2%) were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

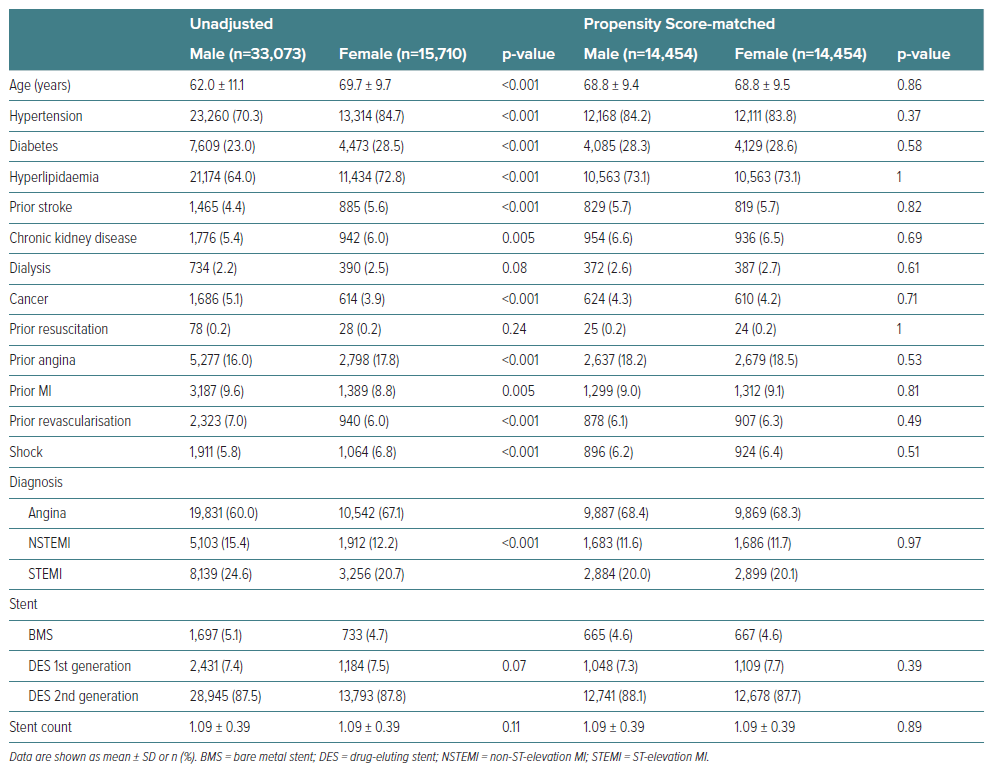

Females were older by 7.7 years on average and more often had cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, history of angina or stroke, than males. MI was less frequent, while shock was more prevalent among females than males (all p<0.001) (Table 1).

Unadjusted Observed Survival and Relative Survival of Males and Females

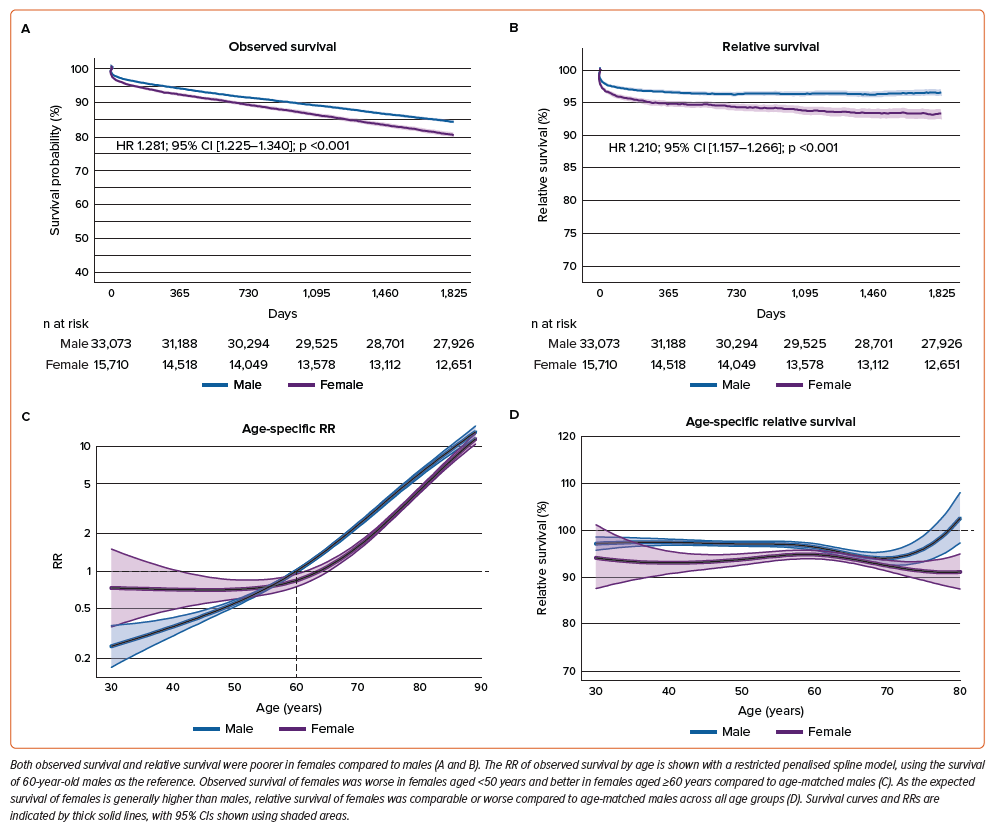

Observed survival was directly calculated from the study cohort (Figures 2A and 2B), while relative survival was calculated by comparing the observed survival in the study cohort and age- and sex-matched expected survival in the general population (Figures 2C and 2D).

Both observed and relative survival rates were lower in females compared to males (HR 1.281; 95% CI [1.225–1.340] versus HR 1.210; 95% CI [1.157–1.266]; all p<0.001) (Figures 3A and 3B). In the observed survival spline plot against age, the RR increased consistently and steeply according to age in males, whereas in females, it increased curvilinearly, resulting in higher RR in females aged <50 years and lower RR in females aged ≥60 years compared to age-matched males (Figure 3C). Additionally, in the relative survival spline plot against age, females aged 40–60 years had lower relative survival than age-matched males (Figure 3D).

Observed Survival and Relative Survival of Males and Females, Adjusted by Matching of Propensity for Clinical Characteristics

Sex-specific differences in age and clinical characteristics were balanced after age group-stratified matching (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Most of the excluded patients during matching process were relatively young males (Supplementary Figure 1D).

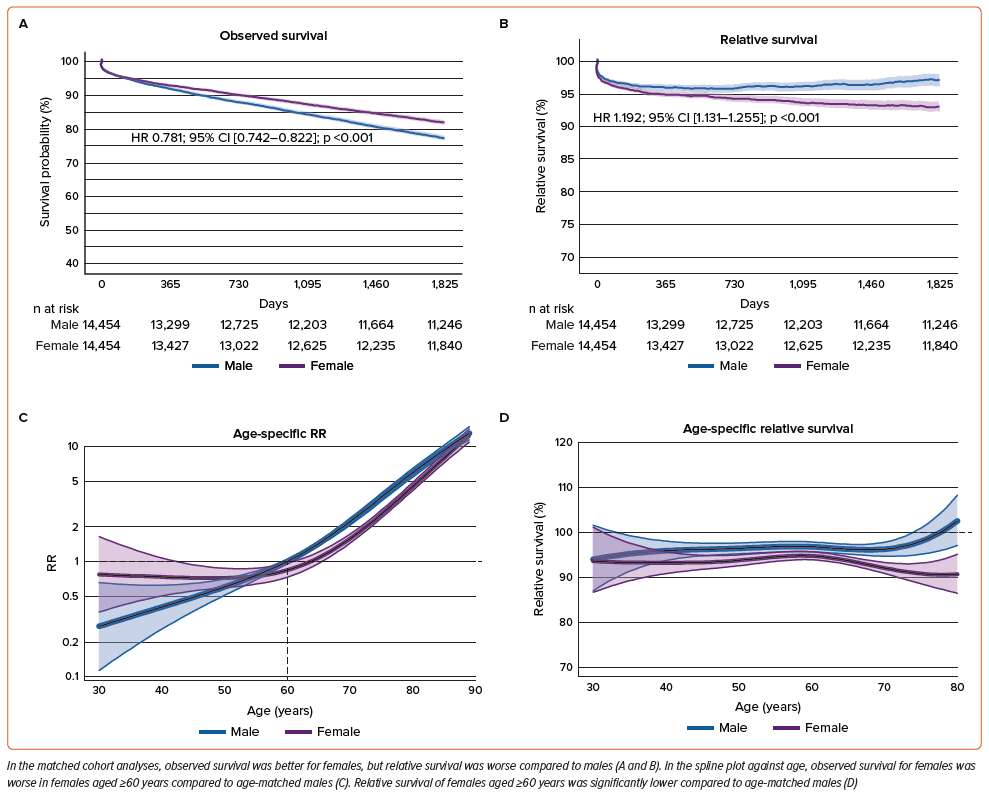

In this propensity-matched cohort, observed survival for females was higher compared to males (HR 0.781; 95% CI [0.742–0.822]; p<0.001) (Figure 4A), reflecting the exclusion of younger males. However, relative survival for females remained lower compared to males (HR 1.192; 95% CI [1.131–1.255], p<0.001) (Figure 4B). The spline plots of adjusted observed and relative survival against age showed patterns similar to the unadjusted analyses. The RR increased consistently with age in males, while it increased curvilinearly in females, resulting in lower RR for females aged ≥60 years compared to age-matched males (Figure 4C). Additionally, relative survival for females aged 40–60 years was marginally lower than age-matched males, and for females aged >60 years, it was significantly lower than age-matched males (Figure 4D).

The trend of lower observed and relative survival rates for females in unadjusted analyses, and the higher observed but lower relative survival for females in adjusted analyses, was also found in analyses conditional on surviving 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years (Supplementary Figures 2–9 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

The main discovery of this study is that older females aged ≥60 years and following PCI had lower relative survival rates compared to age-matched males. Specifically, while young females showed poorer observed survival, older females had better-observed survival compared to age-matched males. However, because females generally have higher expected survival rates than males, the relative survival of females was either comparable to or lower than that of males. However, after adjusting for higher burden of clinical risk factors in females, relative survival rates were comparable between young females and age-matched male and lower in older females compared to age-matched males. These sex-specific differences were consistently observed in conditional survival analyses at 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years.

The major strengths of our study are the usage of a large-scale, real-world nationwide cohort that included nearly all PCI cases, comprehensive evaluation of both relative and conditional survivals, long-term follow-up period spanning 5 years, and complete data for primary endpoint. The combination of observed and relative survival analyses, coupled with conditional survival, provides an intuitive and clinically meaningful comprehensive overview of sex-specific outcomes following PCI. A particularly noteworthy finding of our study is that females in their 70s showed higher observed survival rates but relative survival rates compared to age-matched males (Supplementary Table 2). These findings suggest that 70-year-old females undergoing PCI may not be as healthy as age-matched males and may warrant further excessive risk reduction strategies. Our results emphasise the importance of incorporating relative survival measurement in PCI outcome analysis.15,19

The relative survival of females undergoing PCI was generally not better than males across all age groups. As the natural survival rate of females is higher than that of males in most modern populations and regions, the sex-specific differences following PCI might be caused by a complex interaction of biological, environmental, and social factors.14,19–23 Previous studies have explored various causes for these disparities, including older age, higher cardiovascular risk factor burden, underdiagnosis due to atypical or delayed clinical presentation, less aggressive and evidence-based treatment, social factors, and higher rate of non-cardiac deaths among females.4,24–26 Our study suggests that these factors remain plausible and may apply to young and older females differently. Our prior study showed that the worse observed and relative survival of young females compared to those age-matched males disappeared after adjustments for the clinical characteristic.27 Therefore, deaths not directly related to coronary artery disease, such as non-cardiac or social factors-related death, might contribute to the lower survival of old females.

In a meta-analysis of 21 randomised PCI trials, unadjusted mortality rates were higher for females, but after adjustment, they were comparable to those of males.5 Two studies conducted in South Korean populations showed apparently better-observed survival rates for females.27,28 These conflicting findings can be clarified by introducing relative survival, as shown in our study. Since females generally have higher natural survival rates in most countries, apparently better or similar observed survival does not always imply better outcomes for females after PCI. Our study demonstrated that the relative survival of females could be similar or even lower than that of males.14

In the Mayo Clinic PCI registry study, there was a shift from predominantly cardiac death to predominantly non-cardiac deaths over 20 years, contributing to a higher risk of all-cause death in females due to increased non-cardiac deaths.4 Similar trends were observed in a meta-analysis of randomised PCI trials and a Canadian registry.25,29 Considering these findings and the increasing life expectancy in industrialised countries, the lower relative survival of females in our study might be presumed to be affected by the longer follow-up period and the subsequent rise in non-cardiac deaths.30,31 Unfortunately, our study lacks data on disease-specific death rates, preventing us from determining relative survival free from cardiac or non-cardiac death; only relative survival free from all-cause death was available. Since cardiac death and non-cardiac death are mutually exclusive events, future studies should include competing risk analyses alongside cause-specific survival and relative survival analyses.32

The relative survival of males aged ≥80 years exceeded 100%. This “apparently healthier status of the octogenarian males undergoing PCI compared with age-matched males in the general population” can be explained by the following. First, the 5-year mortality risk of octogenarian males undergoing PCI may be better than that of males with untreated or undiagnosed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which has a prevalence of 31% to 68%.33,34 Second, PCI might be selectively performed in octogenarians without major illness, such as major non-cardiac disease, malignancy or functional limitations. Third, the relative survival might be overestimated due to non-comparability of clinical characteristics between the study cohort and the general population. Patients undergoing PCI typically have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors compared to the general population. This means that the survival of patients who did not undergo PCI may not be directly comparable to that of the general population. This non-comparability can be adjusted using the proportion of deaths caused by a specific disease of interest in the general population via Hinchliffe’s method, which was unfortunately not available in our study.35,36 Baart et al. investigated the relative survival of patients undergoing PCI and showed that the difference between the unadjusted and adjusted expected survival was generally very small.15 Therefore, any bias due to non-comparability in relative survival is unlikely to significantly affect the main results of our study.

Study Limitations

The major limitations of our study are as follows. Retrospective administrative data were analysed, which only recorded all-cause death and did not capture patient-reported outcomes. The severity and complexity of coronary artery disease, complete or incomplete revascularisation, and the presence of myocardial injury, which are known to differ by sex, were not included. Detailed clinical data, including laboratory test findings, time from symptom onset to visiting hospital or catheterisation, and lifestyle data, such as smoking or exercise, were also unavailable. Specific clinical findings, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection, which is particularly common in young women, delays in presentation of seeking medical care, smaller body size, subclinical myocardial dysfunction, including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and less aggressive pharmacological therapy might contribute to the sex-specific differences, but were not accounted.37–40 Although we reported conditional survival on surviving 30 days, specific procedure-related complications, including stroke or bleeding events, were not investigated. The impact of hormone replacement therapy, which has been reported to be used by 15.3% of South Korean women, was not assessed.41 Our results reflect the clinical practice in South Korean hospitals and may not be applicable to other ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Our study shows that females undergoing PCI have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, and their post-PCI survival rates are lower than males, mainly due to poorer outcomes in older females. Recognising these facts can enhance risk reduction strategies and improve clinical outcomes for females undergoing PCI, especially older females.

Clinical Perspective

- Females undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) had a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Relative survival of females after PCI was lower than that of males, which was mainly due to poorer outcomes among older females.

- Improving clinical outcomes of older females undergoing PCI would require a comprehensive approach for excessive risk reduction.