With a proportionally larger older population, the disease burden of AF is greater in the Asia-Pacific region than other areas of the world. By 2050, approximately 72 million people in the area will have AF.1

Despite the potential risks of major bleeding, oral anticoagulation (OAC) has a clear net benefit as it is highly effective in preventing ischaemic strokes in AF patients.2 Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have emerged as alternatives to vitamin K antagonists (VKA) for the prevention of thromboembolic events (TEE) in AF patients.

DOACs interfere with thrombus formation by direct inhibition of thrombin or through inhibition of factor Xa (FXa), which converts prothrombin to thrombin.3 Dabigatran etexilate mesylate is a competitive direct thrombin inhibitor, while rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban are FXa inhibitors.

This consensus aims to guide clinicians to manage AF with reference to issues pertinent to Asia, such as the underuse of OAC and inappropriate dose reduction of DOAC. The authors were part of the guideline working committee and the guidelines were based on available evidence that were appraised based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) as:

- High (authors have high confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect).

- Moderate (authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect).

- Low (true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect).

- Very low (true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).4

Each author then indicated their agreement to each statement (agree, neutral or disagree) via an online poll. Consensus was considered to have been reached when 80% of votes were agree or neutral.

Indication for Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with AF

Statement 1. DOAC use is recommended over warfarin in DOACeligible AF patients.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Consistent evidence from the RE-LY, ROCKET-AF, ARISTOTLE and the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), comparing DOACs with warfarin in AF patients demonstrated at least non-inferiority of DOACs for reducing stroke or systemic embolism (S/SE) risk, and a superior safety profiles with reduced intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) rates.5–8

Meta-analysis of these RCTs showed that DOACs significantly reduced S/SE risk compared with warfarin driven, at least in part, by reducing haemorrhagic strokes.9 DOACs significantly reduced all-cause mortality and ICH but with increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. These results show that, compared with warfarin, DOACs have a favourable risk-benefit profile. The relative efficacy and safety of DOACs were consistent across a wide range of patients. Concurring real-world evidence showed that DOACs were associated with reduced ICH risk and similar rates of S/SE compared with warfarin.10

Consistent with other AF management guidelines and consensuses, this panel recommends DOAC use over warfarin in Asian DOAC-eligible AF patients.11–14 This is supported by multiple Asian studies and systematic reviews documenting the efficacy and added safety of DOACs in preventing S/SE among AF patients.15–21

Statement 2. DOACs can be used in patients with valvular disease in the absence of moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or mechanical heart valves.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of pivotal trials have been summarised elsewhere.22 Patients with concomitant moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or prosthetic/mechanical heart valves were excluded from pivotal RCTs.5–8 It was demonstrated that compared to warfarin, dabigatran use increased TEE rates and bleeding complications in AF patients with mechanical heart valves; hence there is a lack of benefit and excess risk.23 Conversely, patients with valvular heart disease who did not meet the exclusion criteria were included in pivotal trials.5–8,22 An ongoing trial, INVICTUS-VKA (NCT02832544), aims to evaluate DOAC efficacy and safety compared with warfarin in patients with rheumatic heart disease.

Patients with non-AF indications for anticoagulation were excluded and few AF patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) were included in these DOAC trials.5–8 Large retrospective studies have demonstrated that DOAC-treated AF patients with HCM have comparable rates of S/SE and major bleeding and lower mortality than warfarin-treated patients.24 Despite limited prospective data, AF patients with HCM may be eligible for DOACs.

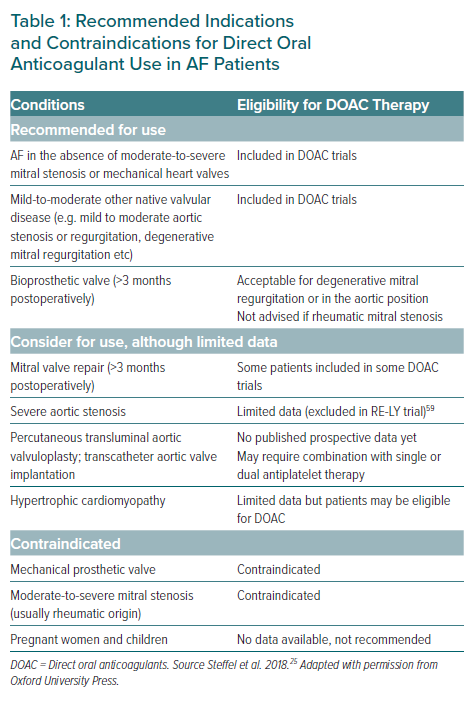

DOACs have not been evaluated for use in pregnant women and children and should not be used for these patients. Table 1 summarises the recommended indications and contraindications for DOACs in AF patients.25

Statement 3. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is well-validated; the CHA2DS2-VA score can be considered for use in practice.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 95% agree, 0% neutral, 5% disagree.

Stroke risk assessment forms a critical part of AF management.11–14 The identification of AF patients at elevated stroke risk would allow targeted prescription of oral anticoagulation to the appropriate subgroup of AF patients with a favourable benefit-risk ratio.26 Multiple clinical, anatomical and biochemical risk factors for stroke have been identified in AF patients.27 However, a simple, reliable and widely accepted risk score such as the CHA2DS2-VASc would be more practical for front-line clinicians than a more complex risk score involving multiple other non-clinical factors, even if the latter is more accurate (with a marginally higher C statistic).28,29

Clinicians also need to be aware of the dynamic nature of individual components of the CHA2DS2-VASc risk score.30,31 Almost half of AF patients initially at low stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc 0 or 1) are no longer low risk after a mean follow-up of 4 years.32 The CHA2DS2-VASc score increases in about 12% of initially low-risk AF patients each year – hence it would be reasonable to reassess this risk score more frequently.33

Recent studies have attempted to improve the accuracy of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in several east Asian populations. Lower ages have been proposed for the scoring and hence initiation of anticoagulation.34,35 If the tipping point for DOAC use was a stroke risk of 0.9% per year, there would be different age thresholds for Asian AF patients with different other single risk factors beyond gender.26,36 However, having multiple age thresholds would increase the complexity of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Until further data is available and a more widespread consensus develops among Asian AF physicians, it is reasonable to continue to use the traditional CHA2DS2-VASc score (as published in the 2020 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AF) for Asian patients.37

Sex category (Sc) in the CHA2DS2-VASc score is a stroke risk modifier rather than a risk factor per se.38,39 If a more accurate stroke risk prediction is desired, the CHA2DS2-VASc score should be used.40,41 However, if the intent of the physician in using the risk score is to determine when anticoagulation is indicated, as will be discussed in statement 4, and the threshold is determined to be CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 for men and ≥2 for women, then Sc becomes unnecessary and CHA2DS2-VA can be reasonably used with a recommendation to start DOAC anticoagulation when CHA2DS2-VA ≥1.42 This would provide a simplified and consistent threshold recommendation for both sexes as per the Australian AF guidelines.43

Statement 4. DOAC use is recommended in Asian AF patients with CHA2DS2-VA ≥1 or CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 (for men) and ≥2 (for women).

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 90% agree, 5% neutral, 5% disagree.

The annual incidence of stroke in Asians is generally higher than in white people, particularly for patients with CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 0–1 (Supplementary Table 1). Thus, while American and European guidelines recommend that OAC be considered in patients with >1 risk factor for stroke (besides being a woman), this panel recommends that DOACs be used in Asian patients with CHA2DS2-VA score ≥1.11,14,37 If clinicians use the CHA2DS2-VASc score, then we recommend OAC be considered when CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 (for men) and ≥2 (for women) as per current major AF guidelines.

It should be noted that HCM patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc / CHA2DS2-VA score of 0 should still be anticoagulated.14

Statement 5. Elderly patients should not be excluded from anticoagulation for stroke prevention and DOAC use is recommended over warfarin.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Post-hoc analyses of pivotal DOAC trials have been reviewed in another position paper; stroke risk-reduction benefits of DOACs, compared with warfarin, were maintained in both older and younger patients with no significant difference in overall major bleeding and ICH rates across all age groups.44 These studies demonstrated that major bleeding risk markedly increased with age, underscoring the need for anticoagulation strategies with improved safety profiles to mitigate bleeding risk.44 A meta-analysis of the four RCTs also showed that, compared with warfarin, DOACs decreased S/SE risk in people aged ≥75 years, without significant differences in the overall risk of major bleeding.9 A retrospective observational study in elderly Taiwanese AF patients (aged ≥90 years) showed that, compared with warfarin, DOACs (dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban) were associated with lower ICH risk and no difference in ischaemic stroke risk.45

These results, as well as those from other Asian studies, show that efficacy and safety of DOACs are preserved in elderly populations.45,46 Since stroke and major bleeding risks increase with age, DOAC use is likely to yield greater absolute risk reduction and greater net clinical benefit in elderly populations when compared with warfarin.

In very old patients who may otherwise be considered ineligible for oral anticoagulation therapy due to frailty, some countries may consider lowering the dose if well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of this strategy. A Phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that included Japanese patients aged ≥80 years found low-dose edoxaban (15 mg once daily) reduced the risk of S/SE compared with placebo (p<0.001) although gastrointestinal bleeding was also increased in the edoxaban group.47 However, in the absence of such compelling clinical data, the approved recommended doses should be used.

Statement 6. Aspirin or other antiplatelet agents should not be used for stroke risk management in AF patients.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Current evidence does not support the use of aspirin and other antiplatelet agents for the management of the risk of stroke in AF patients.48,49 A meta-analysis (n=13,000) showed that dose-adjusted warfarin was substantially more efficacious than antiplatelet therapy for stroke risk reduction in AF patients.48 Warfarin was also superior to aspirin in preventing S/SE in AF patients ≥75 years without increasing major bleeding rates.44,50

With alternative therapeutic options available, such as warfarin, and DOACs having greater efficacy in stroke risk reduction and comparable overall safety profiles with aspirin, antiplatelet therapy should not be used for stroke-risk management in AF patients. This recommendation is consistent with other guidelines and consensus.12–14

Dose Regimens of Direct Oral Anticoagulants

Statement 7. Trial-approved doses of DOACs and/or doses recommended in respective country guidelines/regulations should be used, i.e. DOAC dose should not be reduced inappropriately.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Only doses of DOACs evaluated in pivotal trials have been demonstrated to be at least non-inferior to warfarin in thromboembolic risk-reduction efficacy, with superior safety profiles in terms of reduced ICH risk.5–8 A meta-analysis of landmark DOAC trials also demonstrated the safety profile of DOACs over warfarin in Asians and non-Asians with significant reductions in major bleeding and ICH.51 Nonetheless, patients are frequently underdosed. A retrospective cohort study of about 15,000 AF patients treated with DOAC showed that 13.3% of patients with no renal indication for dose reduction were potentially underdosed.52 The study also found that apixaban underdosing was associated with a fourfold increase in stroke risk with no statistically significant difference in major bleeding risk.52 Several real-world studies in Asia also reported much higher rates of underdosing, ranging from 27% to 36% of patients with suboptimal outcomes.53–56 Underdosed patients were generally found to have a higher ischaemic stroke risk compared to those receiving appropriate doses.

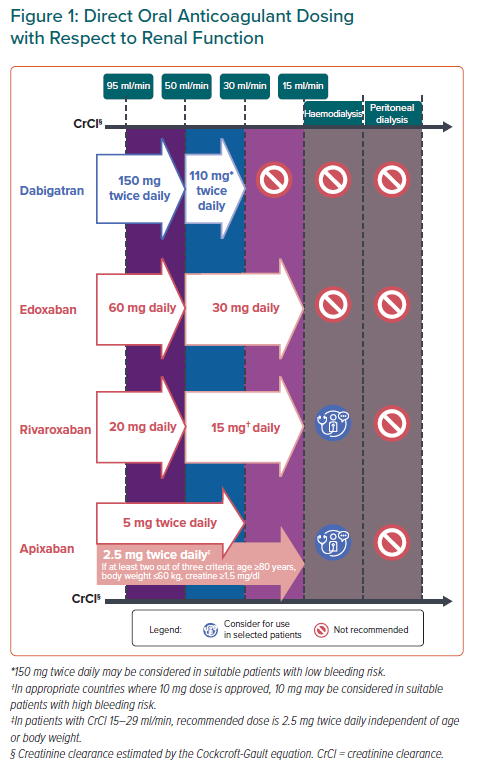

Except in countries where population-specific evidence demonstrated that reduced doses of DOACs are effective for thromboembolic risk reduction, trial-approved doses of DOACs should be used, even in Asian populations. Recommendations for DOAC dosing regimens with respect to approved dose-reduction criteria and renal function are summarised in Figure 1.

Clinicians should also be mindful of the potential interaction of DOACs with other drugs, including herbal medicines and traditional Chinese medicine, especially those that modulate CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein activity although data on these potential interactions are limited.57 The clinical impact of these potential interactions is still not established, however, a literature review found 194 verified reports of interactions with anticoagulants or antiplatelets with 79.9% attributable to pharmacodynamic interactions.58 Some of these interactions (mostly associated with danshen, dong quai, ginger, ginkgo, licorice, and turmeric) resulted in increased bleeding risks.

Statement 8. Rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban can be used in patients with severe renal impairment – creatine clearance (CrCl) 15–29 ml/min – with appropriate dose adjustment.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 90% agree, 5% neutral, 5% disagree.

Safety and efficacy of DOACs relative to warfarin in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) 30–59 ml/min were consistent with that of patients with normal renal function.59,60 All DOACs can be used in Asian patients with CrCl ≥30 ml/min (Figure 1).

The RE-LY trial showed that the 110 mg twice daily dose of dabigatran had similar thromboembolic risk reduction efficacy and lower major bleeding rates than warfarin.5 The European Medicines Agency recommended that dabigatran be used at 110 mg twice daily in patients with CrCl 30–50 ml/min with high bleeding risk. Since Asians have higher risks of major bleeding and ICH compared with non-Asians, this panel recommends that dabigatran be used at 110 mg twice daily in AF patients with CrCl 30–50 ml/min.44 Since dabigatran is predominantly (80%) eliminated via renal excretion, dabigatran use in patients with CrCl <30 ml/min is not recommended in agreement with European guidelines.3,14

DOAC RCTs mostly excluded patients with CrCl <30 ml/min and limited randomised data are available regarding DOAC use in patients with CrCl 15–29 ml/min. However, based on pharmacokinetic studies and renal excretion characteristics, FXa inhibitors have been approved in Europe for AF patients with CrCl 15–29 ml/min. Evidence from small retrospective studies also showed that reduced doses of FXa inhibitors in patients with CrCl 15–29 ml/min did not lead to increases in major bleeding or thrombotic events.61,62

Similar to other guidelines, this panel recommends that reduced doses of rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban, but not dabigatran, can be considered for patients with CrCl 15–29 ml/min.13,25 Various formulae to estimate CrCl result in slightly different values: the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formulae generally result in higher values among patients with advanced age or low body weight compared with the Cockcroft-Gault (CG) formula.63,64 These variability may lead to inappropriate dosing with the use of CKD-EPI or MDRD among these subgroups. Hence, guidelines recommend the use of the CG formula in CrCl estimation.37,43,63

Statement 9. Rivaroxaban and apixaban may be used in patients with end-stage renal disease on haemodialysis.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 64% agree, 27% neutral, 9% disagree.

Pharmacokinetic studies showed no significant change in systemic exposure to FXa inhibitors pre- or post-haemodialysis, indicating that haemodialysis did not significantly impact FXa inhibitor clearence.65

Apixaban undergoes approximately 27% renal clearance.65 Compared with subjects with normal renal function, systemic exposure of apixaban increased 36% with no increase in maximum plasma concentration in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (CrCl <15 ml/min) on haemodialysis. Rivaroxaban undergoes approximately 33% renal clearance and, compared with subjects with normal renal function, systemic exposure to rivaroxaban increased 56% in ESRD subjects on haemodialysis, an extent similar to patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl 15–29 ml/min) not undergoing dialysis.65

Recent registry-based studies also showed that compared with warfarin, rivaroxaban and apixaban use in AF patients with severe renal impairment or undergoing haemodialysis is associated with significantly less major bleeding events but no significant reduction in thromboembolic risk.66,67 However, these studies did not specify the duration of OAC treatment and whether warfarin-treated patients were within therapeutic range. The RENAL-AF trial, which compared apixaban with warfarin in ESRD patients on haemodialysis, was terminated early with inconclusive findings relative to bleeding and stroke rates.68

Despite the current lack of prospective data, pharmacokinetic studies and real-world evidence suggest that rivaroxaban and apixaban may be used in ESRD patients on haemodialysis. Conversely, clinical and observational data to support edoxaban use in these patients are relatively lacking. Although the pharmacokinetic profile of edoxaban in ESRD patients on haemodialysis is similar to that of other FXa inhibitors, FDA labelling states that edoxaban is not recommended in patients with CrCl <15 ml/min.65,69 This position may change should further evidence emerge, perhaps from the ongoing AXADIA study (NCT02933697).

Concomitant DOAC and Antiplatelet Use in AF Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome or Who Have Undergone Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Statement 10. Following percutaneous coronary intervention, triple therapy (DOAC + aspirin + P2Y12 inhibitor) is recommended for up to 1 month (keeping it as short as possible), and dual therapy (DOAC + P2Y12 inhibitor) is recommended for up to 12 months, after which the patient may be maintained on DOAC monotherapy.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 64% agree, 27% neutral, 9% disagree.

Statement 11. The duration of triple therapy may be lengthened or shortened depending on the patient’s thrombotic and bleeding risks.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Early Triple Antithrombotic Therapy with DOAC + Aspirin + P2Y12 Inhibitor

Although optimal combination and duration of antithrombotic therapy in AF patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are not well-established, expert consensus have recommended a short period of triple antithrombotic therapy in suitable patients.11–14

Four RCTs of AF patients who underwent PCI and/or presented concomitant acute coronary syndrome (ACS) showed that, compared with standard triple therapy (STT) of dose-adjusted warfarin plus dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), DOACs + P2Y12 inhibitor led to lower rates of major or clinically relevant bleeding.70–74 Clinically significant bleeding occurred in 16.1% of aspirin-treated patients compared with 9% of patients receiving aspirin-matched placebo (p<0.001) in the AUGUSTUS trial.71 Although not statistically significant, the rates of stent thrombosis in placebo-treated patients was almost twice that of patients treated with aspirin.71 Stent thrombosis rates in the ENTRUST-AF PCI trial were also higher in the dual therapy group (edoxaban + P2Y12 inhibitor) than the STT group. However, these studies were not powered to detect statistically significant differences in stent thrombosis rates between treatment groups.74

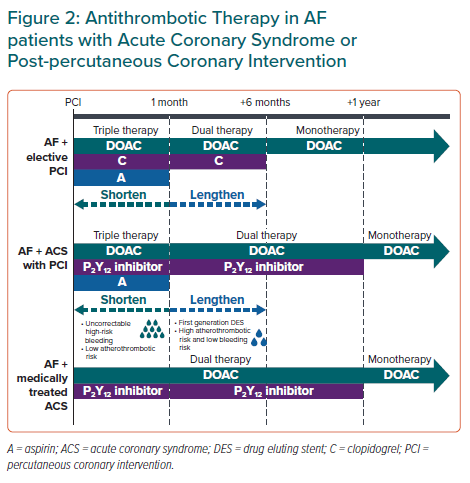

Recent meta-analyses showed significantly increased stent thrombosis rates with early-dual versus triple antithrombotic therapy, which do not support the use of dual therapy immediately after PCI in Asian AF patients.73 This panel recommends a short duration of triple therapy, of up to 1 month (keeping it as short as possible), following PCI in AF patients; duration of triple therapy may be tailored based on the relative thrombotic and bleeding risks before transitioning to dual therapy. For AF patients with ACS not undergoing PCI, early dual antithrombotic therapy (DOAC + P2Y12 inhibitor) is reasonable (Figure 2).

Mid-term Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with DOAC + P2Y12 Inhibitor

Several trials have demonstrated that dual therapy with DOAC + P2Y12 inhibitor reduced bleeding risk compared with STT.70–72,74 Consistent with other guidelines, dual therapy is recommended for up to 12 months, corresponding to the duration evaluated in most trials (Figure 2).13,14

Long-term Monotherapy with Direct Oral Anticoagulants

The AFIRE trial in AF patients with chronic coronary artery disease showed that, compared with the combination group (rivaroxaban + single antiplatelet), rivaroxaban alone resulted in no significant difference in TEE but reduced bleeding events and mortality.75 Global guidelines also recommend OAC monotherapy 12 months after PCI or ACS in AF patients.12–14,25 DOAC monotherapy is recommended for most patients after 12 months post-PCI in line with statement 1, (Figure 2).

Transitioning to Direct Oral Anticoagulants from VKA and Vice Versa

Statement 12. When switching from VKA to DOAC, DOAC can be started the same day if the international normalised ratio (INR) <r;2 or the next day if INR is 2–3. If INR >r;3, INR should be reassessed after an appropriate interval as determined by the clinician, before deciding on when to switch from VKA to DOAC.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 90% agree, 10% neutral, 0% disagree.

Major bleeding risk in patients with INR >3 is twice that of when INR = 2–3 while TEE risk increases by at least two-fold with INR <2.14 Given the quick onset of action and short half-life of DOACs, these agents can be started on the same day if INR <2, or the following day if the patient is in the therapeutic INR range (2–3).3 If INR >3, DOACs should be withheld until the INR is at the indicated threshold (Supplementary Figure 1).

Statement 13. When switching from DOAC to VKA, VKA should be started while the patient is on DOAC. DOAC can then be stopped once the INR >2 (if target INR is 2–3). INR should be reassessed 1–2 days after stopping DOAC.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 95% agree, 5% neutral, 0% disagree.

VKAs have a slow onset of action and it may take days before the INR is in therapeutic range. Thus, DOAC and VKA should be administered concomitantly until the INR is in the appropriate therapeutic range. DOACs present in the body may also affect the accuracy of INR measurements.25 Depending on the patient’s renal function, INR should be reassessed 1–2 days after DOAC discontinuation to ascertain INR levels while solely on VKA and ensure adequate anticoagulation.

Periprocedural Management

Statement 14. Avoid unnecessary or prolonged interruption of DOAC therapy for surgical procedures in AF patients.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

Statement 15. Parenteral anticoagulation overlap with DOAC therapy is not advised.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

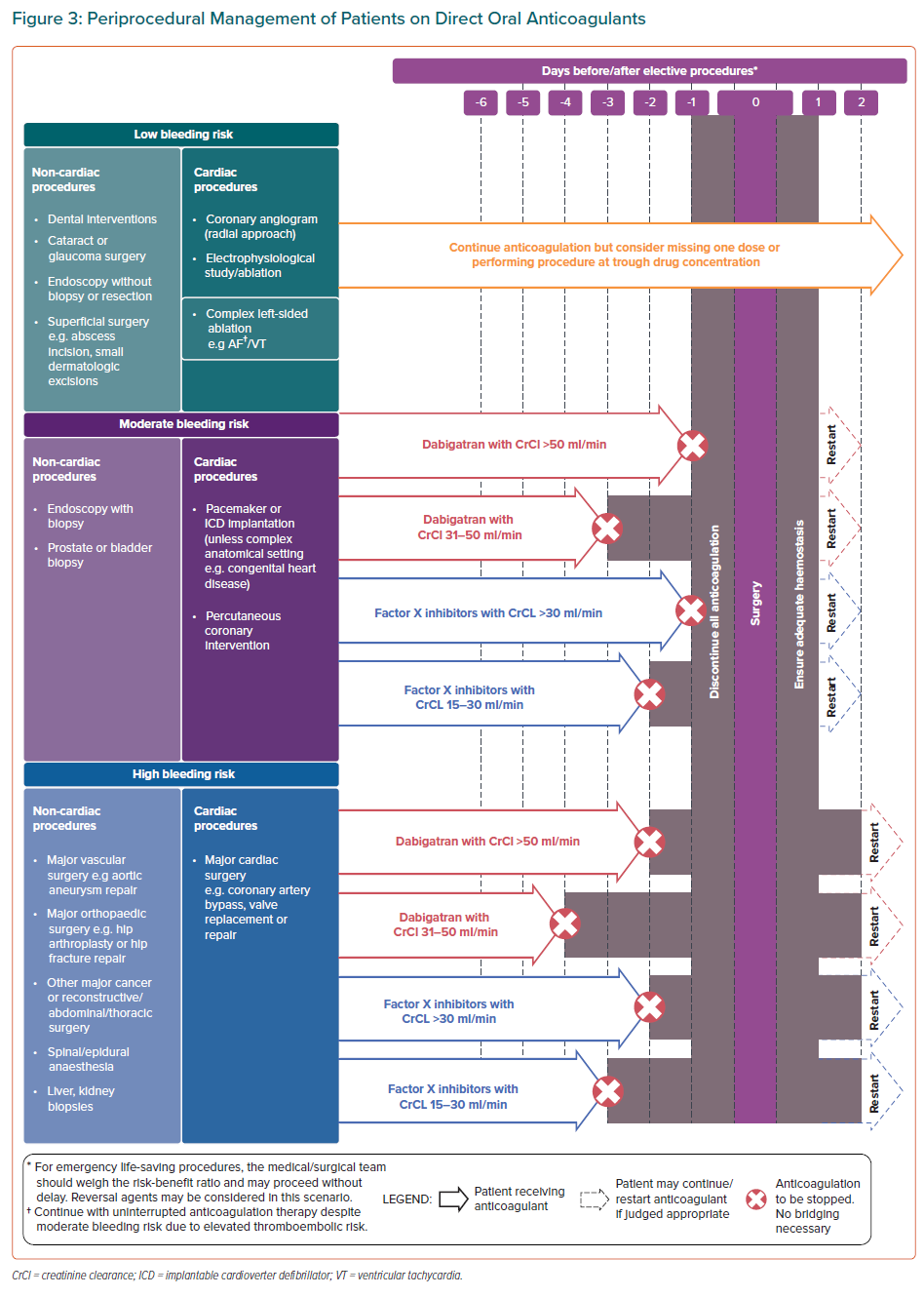

Unnecessary prolonged interruption of DOACs should be avoided given that periprocedural interruption/cessation of DOACs increased TEE risk by around 20-fold.76 Patient characteristics, including age, renal function, history of bleeding complications and concomitant medications, should also be considered when deciding to discontinue or restart DOACs.

Recent evidence from the PAUSE cohort study, evaluating the safety of a standardised perioperative DOAC management strategy, showed that omitting FXa inhibitors one day before a procedure with a low-risk of bleeding and two days before a procedure with a high risk of bleeding was associated with a 30-day postoperative major bleeding rate of <2% and a stroke rate of <1%.77

Figure 3 summarises the bleeding risks associated with common elective procedures and the recommended intervals for DOAC interruption prior to these procedures. Less invasive procedures have a relatively low risk of severe bleeding and may not necessitate discontinuation; omitting one dose of DOAC before low-risk procedures may be considered to avoid nuisance bleeding episodes, which can contribute to DOAC therapy non-adherence. Consistent with other guidelines, complex left-sided ablation procedures may proceed with uninterrupted anticoagulation or after omitting one dose of DOAC.78

In patients with renal impairment, a longer duration of DOAC interruption is recommended before procedures with moderate and high bleeding risk. As dabigatran undergoes extensive renal clearance, dabigatran should be stopped earlier than FXa inhibitors in patients with impaired renal function for these procedures.3

The quick onset of action of DOACs makes it feasible to time the interruption of DOACs before a procedure with a predictable decline of its anticoagulation effects.3 Perioperative overlap of DOAC therapy with parenteral anticoagulation (‘bridging’) is not necessary and has been shown to increase major bleeding complications rates without reduction in cardiovascular events.79 DOACs can be resumed after the procedure when the bleeding risk is deemed acceptable.

As with thrombotic risk, bleeding risk is also dynamic, as demonstrated by a Taiwanese study that included 19,566 AF patients treated with warfarin. After a follow-up of 93,783 person years, 61.8% of patients had a change in HAS-BLED score, and an increased score was associated with major bleeding.80 This underscores the need to reassess bleeding risk before deciding to alter anticoagulant therapy.

Management of Bleeding That Occurs While on Direct Oral Anticoagulants

Statement 16. An institution-specific policy should be developed for managing bleeding events, placing focus on the (pro)haemostatic agents available as direct reversal agents which are not widely available for use.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

DOAC-related bleeding events will inevitably increase as the number of patients using DOACs rises. This panel recommends that hospitals implement institution-specific protocols for managing bleeding events as reversal agents are not uniformly available in Asia-Pacific hospitals and a wide diversity of (pro)haemostatic agents are available. Physicians may refer to the HAS-BLED score for identification and modification of bleeding risk factors such as adequate hypertension control, labile INR (on warfarin), excessive alcohol intake and concomitant antiplatelet therapy or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.25 Managing these modifiable risk factors further minimises bleeding risk.

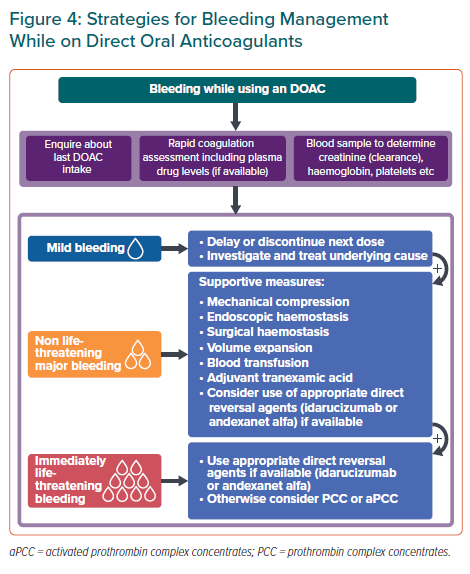

Bleeding management strategies for DOAC-treated patients depend on bleeding severity and on individual patient factors such as time of last DOAC intake. Figure 4 summarises the recommended management strategies for bleeding complications.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) may be considered for volume expansion in major bleeding complications but FFP does not reverse DOAC anticoagulation. Use of direct reversal agents may be considered. Idarucizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds dabigatran with a higher affinity than thrombin, reverses the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within minutes when administered intravenously.25 IV administration of andexanet alfa, a recombinant modified FXa decoy protein, neutralises the effects of direct and indirect FXa inhibitors immediately.25

Where direct reversal agents are unavailable, data from observational studies suggest that coagulation factors such as activated prothrombin complex concentrates may be used to achieve haemostasis in patients who experience life-threatening bleeding while on DOACs.25

Post-bleed Management of AF Patients

Statement 17. Following a major bleeding episode, DOAC should be restarted after the cause of bleed has been corrected. If the cause of bleed is not found, an interdisciplinary consensus should be reached for an individualised anticoagulation strategy.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of agreement: 100% agree, 0% neutral, 0% disagree.

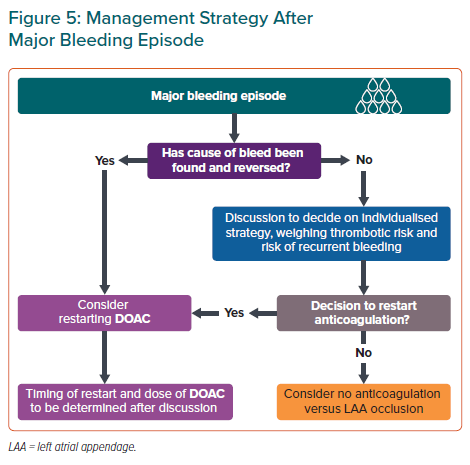

Whether to restart DOAC therapy after major bleeding episodes, such as ICH, gastrointestinal bleeding or a fall/trauma, is a common dilemma. OAC resumption in AF patients after ICH was associated with reduced TEE risk and overall mortality without increased risk of recurrent ICH compared with patients who did not resume OAC.81 Although anticoagulation is contraindicated in those with a history of spontaneous ICH, the panel recommends that DOAC therapy be restarted if the cause of bleed, such as uncontrolled hypertension, has been reversed (Figure 5). Evidence is lacking about when to restart DOACs and timing and dose of DOACs when restarted after a major bleeding episode should be determined after a multidisciplinary discussion.

If the cause of the bleed has not been reversed, an individualised strategy for thrombotic risk management should be reached after a multidisciplinary discussion, weighing the patient’s thrombotic and recurrent bleeding risks. Left atrial appendage occlusion may be considered as an alternative in AF patients unsuitable for long-term anticoagulation (Figure 5).

Conclusion

The 17 statements in this paper provide guidance to front-line physicians on select contemporary issues in Asia, such as the underuse of OAC and inappropriate dose reduction of DOACs.

Click here to view Supplementary Material.